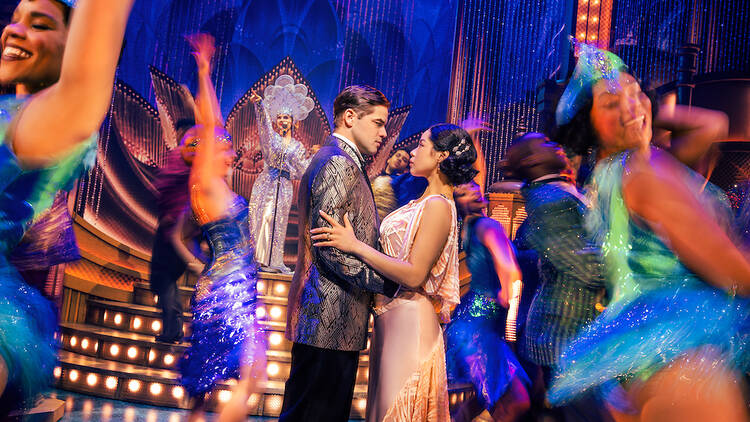

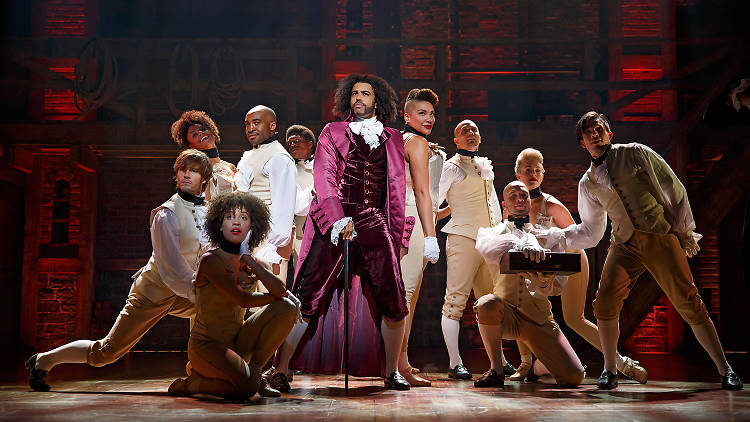

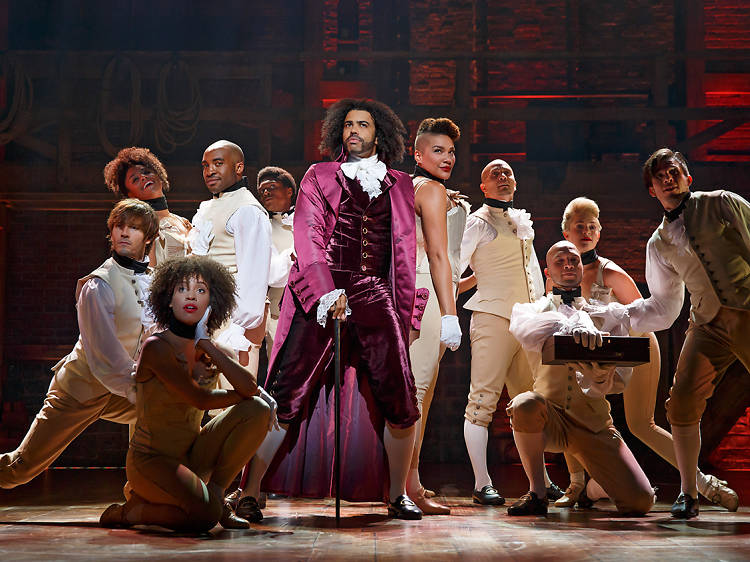

Broadway shows are central to the experience of New York City. The word Broadway is sometimes used as shorthand for theater itself, but it officially refers to the set of 41 large theaters near Times Square, nearly all of which were built before 1930 and most of which seat more than 1,000 people. The most popular Broadway shows tend to be musicals, from long-running favorites like The Lion King and Hamilton to more recent hits like Hadestown and Moulin Rouge!—but new plays and revivals also represent an important part of the Broadway experience. There’s a wide variety of Broadway shows out there, as our complete A–Z listing attests. (For a full list of shows that are coming soon, check out our list of upcoming Broadway shows.)

RECOMMENDED: Find the best Broadway shows

RECOMMENDED: Current and upcoming Off Broadway shows