[category]

[title]

Review

Broadway review by Adam Feldman

Yes, I have seen the new Othello with Denzel Washington and Jake Gyllenhaal, the one that is raking in almost $3 million a week by selling out Broadway’s Barrymore Theatre with tickets priced at up to $900. And no, you probably won’t see it. Jealous? Well, you shouldn’t be. It’s not just that jealousy itself—famously described in Othello as "the green-eyed monster which doth mock the meat it feeds on”—is deleterious to the soul. It’s that this production, though perfectly good in most regards and better than that in several, isn’t worth voiding your purse.

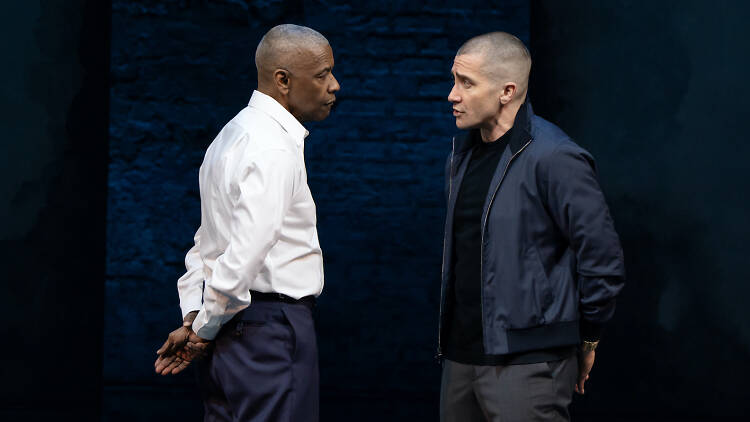

At any rate, but ideally a lower one, you’ll have many opportunities to see Othello in the future, even if it is the least frequently produced of Shakespeare’s four great tragedies; the last Broadway production was in 1982, with James Earl Jones and Christopher Plummer. There are reasons for this relative rarity, which stem from some of the very things that make the play appealing: its swiftness and sweeping passion. The respected general Othello (Washington), a Moor in cosmopolitan Venice, marries a beautiful young Venetian woman, Desdemona (Molly Osborne), to the fury of her wealthy father, Brabantio (Daniel Pearce). But he is soon deceived by his trusted aide Iago (Gyllenhaal) into believing that she is cheating on him with his handsome right-hand man, Cassio (Andrew Burnap). Stirred to rage, he suffocates the faithful Desdemona in their wedding bed.

Othello | Photograph: Courtesy Julieta Cervantes

That may seem straightforward, but Othello is challenging to stage. The story unfurls over a tightly compressed period—about three days—which the farce-adjacent plot requires. Shakespeare takes elements of commedia dell’arte comedy (the crafty servant, the rich old man, the threat of cuckoldry) but gives them a murderous twist and an unhappy ending; and the misunderstandings and miscommunications on which everything hinges could not work if the characters had more time to sort out what’s happening. Yet the particulars of the lies that Iago tells Othello could only have taken place over a much longer span of time. The timelines don’t match up. It already requires a significant leap to believe that Othello could go from doting groom to vengeful killer in such a short time, but to believe he could do so on evidence that makes no sense might require, or at least strongly suggest, something else: that, like the name Shakespeare gave him, Othello hides an inner hell; that the savage has been lurking under the noble all along, just waiting to emerge. And that raises another reason Othello is hard to produce: the question of race.

In Othello, or the Moor of Venice, to use its full name, Shakespeare inverts several themes that he had visited earlier in his other Venetian play, The Merchant of Venice. There, the furious father of an eloping bride is an outsider—Shylock, the Jew—and the new husband is a local Christian, so the play is, grosso modo, a comedy. But here, the father is Venetian and the new groom is the ethnic other: a Moor, with dark skin of the kind that Merchant’s heroine, Portia, dismisses out of hand. (“Let all of his complexion choose me so,” she says with relief when the Prince of Morocco loses the lottery game to marry her.) Which is why, perhaps, Othello is a tragedy. In this reading, the play would imply that Brabantio—who can’t believe his daughter could desire to be in “the sooty bosom of such a thing as thou,” and who dies of grief at her betrayal—was right all along: A marriage between a dark man and a fair woman could only end in tears.

Othello | Photograph: Courtesy Julieta Cervantes

We cannot sanction such a reading today, as explicative as it might be. And it is not, after all, strictly necessary to believe that Shakespeare must have intended it that way; Leontes, in The Winter’s Tale, falls into a similar jealous madness on even less evidence and without outside goading. But like anti-Semitism in Merchant and sexism in The Taming of the Shrew, the possible racism of Othello is a specter that must be reckoned with. This production’s director, Kenny Leon, who tackled race head-on in his 2023 revival of Purlie Victorious, takes pains to decentralize it here. Set in “the near future,” mostly amid American army troops, Othello takes place in a world in which race is not much of an issue. Brabantio’s bigotry gets laughs from the audience, and it appears out of step with the rest of Venetian society, which includes other Black citizens in positions of prominence—including Iago’s wife and Desdemona’s close confidante, Emilia (Kimber Elayne Sprawl).

Perhaps the curiously muted quality of Washington’s performance, especially at the play’s climax, stems from a desire to avoid antiquated tropes about Black men’s violent natures. Only once does Othello’s fury here verge on the bestial; finally overcome by Iago’s lurid insinuations, he falls to the floor and crawls on his stomach, directly at the audience, sticking out his tongue like a lizard. But this reversion seems as much military as animal, and in any case it is soon written off as an epileptic fit. Washington is adept at playing the confident, smiling, easygoing Othello of the play’s first section, but his anger peaks early. Afterward, he is largely impassive and resigned.

Othello | Photograph: Courtesy Julieta Cervantes

This choice is not unjustifiable—maybe Othello is shielding himself from fearful emotions by assuming the impartial mien of a man doing the honorable thing—but it is also anticlimactic. Just as the tragedy should be building momentum, the motor falls out of Leon’s production. The run-up to the finale, in which Iago kills his longtime dupe Roderigo (Anthony Michael Lopez) and seriously wounds Cassio, is confusing and muddily staged, and the tragedy’s final scene is bloodless. When Othello kills Desdemona, he approaches the task with pitying efficiency, as though putting down a beloved pet whose sickness can no longer be denied. Everything from the asphyxiation (accomplished in a highly unconvincing headlock) to Othello’s own suicide feels like an actor going through the motions. In eschewing melodrama, the production goes too far and smothers drama, too.

This Othello does offer an intense, original and compelling depiction of jealousy. But it’s Iago’s jealousy, not Othello’s: his suspicion that Othello has slept with his wife, Emilia; his rage at Cassio’s having taken his rightful place as Othello’s lieutenant. These are always motives for Iago’s malice, but Gyllenhaal makes them the white-hot core of his powerful performance, the coal that fires his hypermasculine truculence. He’s jacked and alert, but beneath his menacing tautness, he’s spiraling out of control. Some Iagos seem to have it all figured out in advance, and take us into their confidence like Richard III; but when Gyllenhaal describes his plans, he’s clearly figuring them out on the fly, in a way that highlights the recklessness of the whole enterprise. It’s so dangerous—so contingent on luck, so apt to go terribly wrong—that it seems like a form of self-destructiveness. (He’s ineluctably caught up in the system he perpetuates; as Emilia points out, before Iago fed false rumors to Othello he was himself the victim of some unknown gossip who “turned your wit the seamy side without / And made you to suspect me with the Moor.”)

Othello | Photograph: Courtesy Julieta Cervantes

This is hardly the first Othello to be stolen by Iago, of course—he has the most lines in the play—and this production has a number of assets beyond Gyllenhaal’s blue-with-greenish-flecks-eyed monster. Osborne’s intelligent Desdemona, as poised as a politician’s wife, is costumed with elan by Dede Ayite to stand out from the sea of camouflage. Burnap is a persuasively callow Cassio, Lopez a suitably dim Roderigo. Sprawl makes Emilia a cynical tough cookie whose mistake, like that of many cynics, is that she isn’t cynical enough; she’s so busy being worldly that she misses the depravity under her nose. (When she berates Othello for his naïveté at the end —“O gull! O dolt, as ignorant as dirt!”—she might be berating herself.) But if you can’t catch this Othello, don’t despair. As much as you may think you need what Othello calls “the ocular proof,” the production is not a must-see.

Othello. Ethel Barrymore Theatre (Broadway). By William Shakespeare. Directed by Kenny Leon. With Denzel Washington, Jake Gyllenhaal, Molly Osborne, Andrew Burnap, Kimber Elayne Sprawl, Anthony Michael Lopez, Daniel Pearce. Running time: 2hrs 40mins. One intermission.

Follow Adam Feldman on X: @FeldmanAdam

Follow Adam Feldman on Bluesky: @FeldmanAdam

Follow Adam Feldman on Threads: @adfeldman

Follow Time Out Theater on X: @TimeOutTheater

Keep up with the latest news and reviews on our Time Out Theater Facebook page

Othello | Photograph: Courtesy Julieta Cervantes

Discover Time Out original video