End of isolation

Delve back into Japanese art history and you’ll see a long tradition of using nature, religion and East-Asian philosophies as subjects, hence the prevalence of waves, mountains, plants and flowers. The most iconic example of this practice is Katsushika Hokusai’s wood print ‘Under the Wave off Kanagawa’ from the series ‘Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji’ (c. 1829-1833), which depicts a giant wave at the cusp of crashing.

However, after almost 300 years of self-imposed isolation, Japan reopened its borders and began trading with the West during the Meiji restoration period (1868- 1912) and with this, Western art, culture and technology flooded into the Japanese consciousness. Just as late 19th century European artists like Edgar Degas and Claude Monet were greatly influenced by their exposure to Japanese art, artists in Japan also reinterpreted their nation’s traditional styles with modern influences. In 1897, the Tokyo School of Fine Arts established the department of Western painting– it was here that many Japanese artists learned of Western art and its themes and techniques.

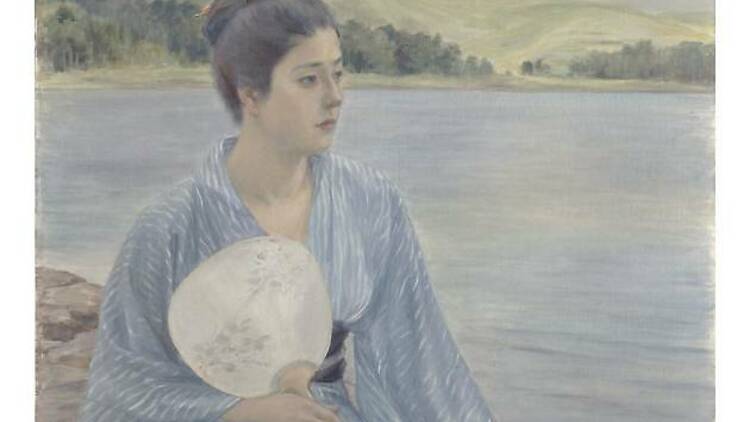

This meeting of minds at the turn of the 20th century can be seen in works such as ‘Lakeside’ (1897) by Seiki Kuroda. Presented at the International Expositionin Paris in 1900, the painting of a Japanese lady sitting and enjoying the cool against a background of a lake and mountains was one of a number of works that led to Kuroda being seen as the father of Japanese modern art. ‘Lakeside’, which can be viewed at Tokyo National Museum, drew critical acclaim from the Parisian art society for combining two very different styles of painting.