Marcel + The Art of Laughter

Theater review by Sandy MacDonald

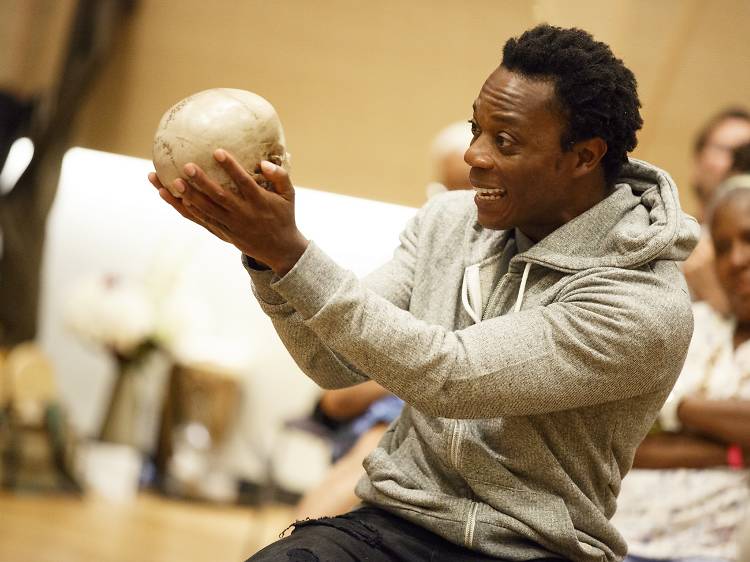

In this topsy-turvy age, as clowns run amok around the world, two professional ones are on hand at Theatre for a New Audience to lend some comic relief: Belgium’s Jos Houben and Italy’s Marcello Magni, original members of London’s famed Théâtre de Complicité. In Marcel, the mostly nonverbal first part of their double bill, Magni—a small, shy, middle-aged man in the Charlie Chaplin mode (minus the antic streak)—is applying for a job of some sort: life, perhaps, or maybe just a clown contract renewal. As Magni strives to surmount inane barriers to success, his taskmaster, played by a tall and sneering Houben, seems determined to keep raising the bar. While this business is not always funny, Magni’s charm keeps it from being tiresome.

The show perks up, especially for those of us who enjoy the intricacies of text, when Houben takes the stage in his The Art of Laughter. Alone onstage with just a table and two chairs, Houben promises a “master class” in physical comedy. But instead of a dry lecture, he embarks on a practicum of fumbles and pratfalls; his minutely calibrated body language is brilliant, especially in a bit resurrected from his Belgian childhood. (When was the last time you saw someone imitate cheese?) Houben’s thesis is that verticality equals dignity, evolutionarily speaking, and thus any threats to the former jeopardize the latter. “Laughter,” he argues, “enjoys pulling down that which elevates itself too much.”

Theatre for a New