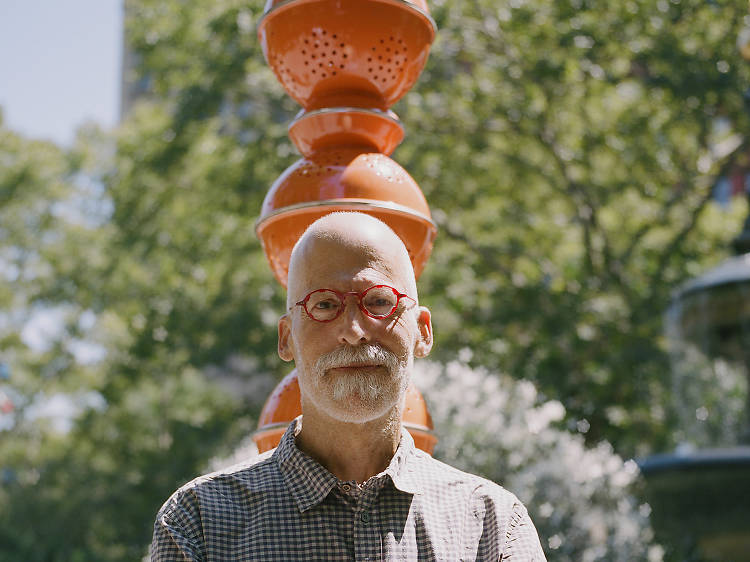

Artist B. Wurtz plants pots and pans as "Kitchen Trees" at City Hall Park

For 50 years, California native B. Wurtz (his preferred moniker) has been employing cheap, throwaway materials to create whimsical, idiosyncratic sculptures that touch upon, as he puts it, “sleeping, eating [and] keeping warm.” He labored under the radar for years, creating small-scale assemblages, but since 2011, he’s enjoyed worldwide success with solo shows at major museums and galleries, and is currently represented by Metro Pictures in Chelsea. Now, he’s stepping into the role of outdoor artist with a Public Art Fund project at City Hall Park. Titled Kitchen Trees, the installation comprises arboreal forms made from pots and pans that are hung with plastic fruit. The artist recently sat down with us to discuss his new work, his passion for recycling and his fascination with plastic.

Photograph: Jason Wyche, Courtesy of Public Art Fund, NY

How did you wind up choosing kitchenware to compose your installation?Since the early 1970s, I’ve been making assemblages out of everyday objects. I wanted people to look at things in a different way, but I also knew I needed to impose some order on the process. So, I came up with the idea of dealing with just three topics—food, clothing and shelter—which are the basics of human existence. Kitchen items fit right into the food category.

Photograph: Jason Wyche, Courtesy of Public Art Fund, NY

Are you making a point about recycling? Some of the everyday objects you use are considered trash—like shopping bags, for instance.Personall