Antigone

Theater review by Helen Shaw

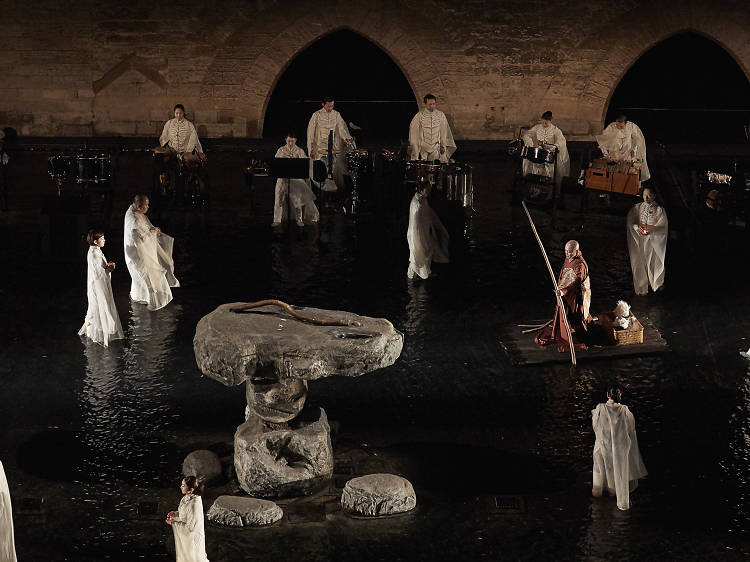

The first image of Satoshi Miyagi’s Antigone is exquisite. Not pretty, not lovely, but exquisite—the kind of beauty that hurts a little. Before the play begins, white robed actors wander ankle-deep through a shallow, rock-studded black lake. In the dimness, they glow like lanterns set loose on a river. This goes on for what seems like ages: The show waits, we wait, as the actors drift through the singing dark. How this watery world will translate to Sophocles’ high-walled Thebes, we don’t know, but for a little while we dream somewhere between life and death, where the shades gather and remember their past.

The preshow can’t go on forever, unfortunately. Soon the Shizuoka Performing Arts Center’s slow-moving production (hosted in New York at the Park Avenue Armory) has to get down to the ancient business of Antigone, her uncle Creon and their struggle over whether to bury a traitorous relative. Miyagi splits the action: Mute dancers embody the characters in carefully choreographed movement up on the rocks, while speaking actors shout their lines from down in the water. Eventually, most of the two dozen company members resolve into a band, standing behind the lake to play Hiroko Tanakawa’s drum-filled score, which has moments of riotous intensity. But the doubling drains the production of crucial tension, and the show becomes less dreamlike than sleepy. It feels aimless and often baffling; Sophocles’ vivid arguments become simple rants, since the