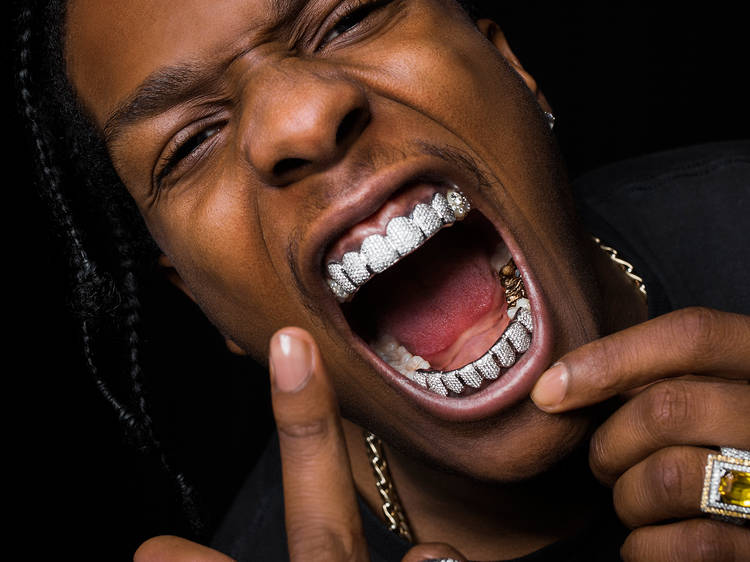

A$AP Rocky is late. Two hours late, to be exact. Then, out of nowhere, he rolls up (literally) to our cover shoot on an electronic skateboard, which he uses to travel from the door of his Escalade to the studio floor, approximately 30 feet away. “I’m just a big kid,” he shrugs, exposing a full-on golden smile—made of real gold—beneath his Céline shades. As with any kid, it’s hard to stay mad at him. But he’s not really a kid. He’s a 26-year-old Harlem-bred rapper who’s headlining the Theater at Madison Square Garden September 22 with fellow headline-making MCs Tyler, the Creator—who was recently banned from entering the U.K.—Vince Staples and Danny Brown. The event tops off a huge four years, during which Rocky’s ascended from releasing a mixtape (2011’s online freebie Live.Love.A$AP) to signing a $3 million deal with Sony, dropping two No. 1 albums and collaborating with Skrillex, Lana Del Rey, Kanye West and, most recently, Rod Stewart on At.Long.Last.A$AP. (The record’s acronym, by the way, is a reference to Allah.)

“You mind if I stay on my skateboard?” he asks politely, then glides around the tiny photo studio with my Dictaphone in his hand, like a New Age Don Draper conducting a meeting. Turns out he’s asking to stay on his skateboard for the whole interview. Yet the request isn’t annoying. His flawless charm could excuse almost anything—even the last-minute demand for herring to accommodate his pescatarianism. The fish remains untouched the entire time he’s here.

Where NYC giant Jay Z took years to make headway, in the blogosphere era, Rocky’s stardom was almost instantaneous. He arrived with all the goods: a region-defying take on a genre thanks to producers such as Clams Casino, who gave him a fluid cocktail sound that resonated like a Valium-laced blunt; and a cooler-than-thou fashion sense to rival his hero Kanye. (When I ask him where he buys duds in town, he responds, grinning while balancing on the board: “Fuck that shit. Let those motherfuckers figure it out.”) Add in a smattering of charisma—yes, even when he says “fuck that shit” he’s oddly likable—and it’s no surprise he scored a starring role as JFK in Lana Del Rey’s video for “National Anthem,” a comedic turn on The Late Late Show with James Corden and a lead part in this summer’s acclaimed indie movie Dope.

But let’s back up. To tell Rocky’s tale—to explain this meteoric rise—you need to start at the beginning. Named after the so-called God MC, Rakim, Rocky came of age while living in an apartment off 116th Street and Morningside Avenue. Inspired by his brother, Ricky, the future hip-hop star started rapping at just eight years old. When he was 13, his brother was gunned down blocks from his home, and Rocky ended up living in homeless shelters with his mother and peddling first weed, then crack, to make ends meet.“I didn’t feel like

I was being bad,” he tells me when I ask him about slinging. “I can tell you why: The prohibition era! Liquor was fucking crack back then. Liquor was weed back then,

wasn’t it?”

I ask him about growing up in the city that invented the genre he’s making a splash in, about the shows he saw when he was younger that inspired him. But Rocky couldn’t afford tickets to gigs. Instead, he found himself sneaking into fashion shows. Opportunities presented themselves there. “We’d go to Phillip Lim, Jeremy Scott, trying to get up in there.” He pauses. “This is no lie. We used to rob people. We were badass kids. We beat them up and shared the Goyard.” Rocky takes his Goyard wallet out of his pocket midskate, flashing the leather fashion brand. “When you’re poor, you share with your boys, like brothers.”

His luck started to turn around when he hooked up with the A$AP Mob—A$AP stands for “always strive and prosper”—and first caught attention with online track “Peso” in 2011. It was A$AP Yams who established Rocky’s radical sound, then posted the results on Tumblr site realniggatumblr. Earlier this year, Yams died from a drug overdose. “I pray to God, and I just hope that when I die, I get to see Yams,” he says soberly, halting the board for a moment.

With a notorious backstory of his own drug consumption, orgies and general hedonism, it’s easy to suggest Rocky would almost rather fall into the rock & roll stereotype of living fast and dying young. “I think you’re right,” he says when I note this. “We all gotta go. You and me. We don’t know when. You can’t be scared. Maybe it’s not time for me to die yet. But if it is? I’m ready. You gotta pray, keep putting good energy into the universe. My mission was to inspire. I’ve done that in so many ways. I’m not joking.”

He’s flabbergasted when I ask exactly how he’s done this. “What do you mean?!?” he asks. “You don’t see how kids dress in 2015? I try to lead by example. Show kids that if I could do it, they can do it.” Then he gets mad at himself and skates to the other side of the room. “That’s such a cliché. I don’t wanna be preaching that shit. When was the last time you heard that? Yesterday?” he says laughing.

After finishing that thought, he zooms back to the other side of the room, building more steam. “If you twist your ankle before the [MTV] VMAs this Sunday…” his publicist chastises. But he ignores her and instead lifts up his shirt. “We gotta free the nipples!” The jokes come fast, incessantly. “I wish I had a six-pack, but I guess I’m just Onepac Shakur!” It’s hard to believe this levity is coming from the same guy who—this year alone—got into a brawl outside a London bagel shop when a passerby threw baked goods at his car, wrote a misogynist rap, “Better Things,” about a sexual encounter that name-checks pop star Rita Ora and is reportedly subject to his former manager’s lawsuit for $850,000 in back pay. “I’m not complex, I’m just complicated,” he chuckles, infectiously. “I know it sounds stupid, but think about it.”

Rocky is an artist you have to think about. He may have rapped about “bitches” who like his “licorice” on huge radio anthem “Fuckin’ Problems,” but his first album contained tracks such as “Phoenix,” which is about suicide, Kurt Cobain and media scrutiny. “Max B,” on his latest, is about economic inequality and prison life and is inspired by a Harlem rapper of the same name who is now serving out a 75-year sentence for conspiring to murder. He goes deep, lyrically and sonically. On A.L.L.A., Rocky flirts with Southern chopped ’n’ screwed beats, East Coast classic swagger and psych sounds, carving out his own recognizable blueprint.

The MC has embraced a new, more hippyish influence on a sound he refers to as “advanced,” which is another way of saying “drug-assisted.” His early stuff was always described variously as dreamlike, the influence clearly being marijuana. But today, he’s attributing his main motivation to dropping acid. Rocky was taking mushrooms five years ago but had his first acid trip in 2012. When asked the context of the trip, he feigns shyness. “Yo,” he laughs. “Okay, without getting anyone in trouble, I was with my homeboy and some trippy celebrity chicks and…” he giggles, smiling to himself and coy when pressed for the names of these so-called chicks. How long did it last? “Too long, man. Twenty-three hours. I was trippin’ till the next day. When I woke up, I was like, Damn! I did that shit! That shit was dope. It was so amazing. It was a-ma-zing.” He drops down to a whisper out of respect for the memory. “Nothing was like that first time.”

Acid changed everything. “I never really gave a fuck, man,” he says of his pre-tripping days. “But this time, I really don’t give a fuck,” he reveals, referring to his complete lack of self-consciousness about putting out A.L.L.A. “I don’t care about making no fucking hits.” I’m thrown by this honesty. Really? He doesn’t care how much his latest album sells? “It’s over 3 million now,” he tells me, when I ask how much it’s sold. “Who gives a fuck? It ain’t Taylor Swift numbers.”

On A.L.L.A., it’s obvious that Rocky’s influential juices flowed in the London studio with acclaimed producer Danger Mouse (Gnarls Barkley, the Black Keys). “It’s so hard to be progressive when you’re trippin’ balls,” he says laughing. “You make some far-out shit!” Rocky describes the studio decorated with “antique, fuckin’ old-ass appliances.” He describes how he and Danger Mouse would stop midway through 3am sessions and watch Woody Allen movies or listen to Pink Floyd, the Beatles and Bad Brains. One time, Virginian rapper Pusha T dropped by and played Rocky a new unreleased song so good he demanded Pusha play it 10 times.

Singer-songwriter Joe Fox was also in the studio, and the story of his involvement is, like a lot of Rocky’s past, legendary: When the MC was leaving after a long recording session at around 4am, he came across a homeless guy in the street playing his guitar and singing. It was Fox, who was unaware of Rocky’s identity. Rocky loved Joe’s voice and invited him into his Uber. They began working together. Instead of disposing of Joe after he completed his contributions on five A.L.L.A. songs, Rocky did quite the opposite: He invited Joe into his home and traveled around the world with him. Such unbelievable stories are Rocky’s salvation. I mean, can you imagine Kanye doing this?

Rocky drops the nice-guy swagger, though, and gets legitimately fired up when he thinks that I’m judging him. During the photo shoot, he presses himself up against a wall, spreads his legs and demonstrates how cops line black men up in NYC. It’s an invitation to discuss Rocky’s recent experience at Oxford University, where a student challenged his decision to abstain from rapping about racist police brutality in America, specifically the incidents in Ferguson. It’s a topic many, many rappers at his level have addressed—from Killer Mike to Talib Kweli. “Let Kendrick and J. Cole deal with that shit,” he retorts. He starts rapping from his record, moving his hands while swooshing through the room on his board. He goes into the song “Dreams,” spitting, “I just had an epic dream like Dr. King / Police brutality was on my TV screen—I specified ‘TV’ because I was in London. Why would I feel compelled to rap about Ferguson? I’m not about to say that I was down there throwing rocks at motherfuckers, getting pepper-sprayed. I’d be lying. Is it because I’m black? What the fuck, am I Al Sharpton now?” He halts the electronic skateboard and looks me in the eye. “I’m A$AP Rocky. I did not sign up to be no political activist. I wanna talk about my motherfuckin’ lean, my best friend dying, girls, my jiggy fashion and my inspirations in drugs. I live in fucking Soho and Beverly Hills. I can’t relate. I go back to Harlem, it’s not the same. It’s a sad story. I gotta tell you the truth. I’m in the studio, I’m in fashion houses, I’m in these bitches’ drawers. I’m not doing anything outside of that. That’s my life. These people need to leave me the fuck alone.”

Speaking of those bitches’ drawers, one thing I can’t help but wonder is whether Rocky, deep down and despite the bragging and lyrical evidence to the contrary, is intimidated by women. “Yes,” he says, absolutely certain. “I know that women are smarter than men. I can’t front. That’s how dope chicks are,” he continues. “I know I gotta lot of chicks up my sleeve, but you all are twice as good.” Then I question the MC, who tells me he calls his mom daily, about the worst thing that a girl could do to him. “The worst thing? She could get you locked up and set up,” he says laughing. “But the worst thing a good girl could do to you is break your heart.” He sighs. “I’m single, man. There’s no one looking after me. I’m all fucked up.”

Rocky returns to jokey form when he notices his entourage. Four guys are with him today, all embroiled in a hilarious exchange about whether there’s really a black member in Maroon 5. “It’s a conspiracy!” says Rocky, as his manager shows him a recent press shot. “Nahhhhh! Can someone put that Tame Impala shit on?!?” he yells, shifting into a dance—on his board, of course—while nuggets from the Australian psych rock band blast in the background.

Rocky deserves to be this giddy—he’s killing it right now, as is hip-hop in general. When I suggest this, that we’re in a golden era following releases from Dr. Dre (Compton), Kendrick Lamar (To Pimp a Butterfly) and hopefully another soon from Kanye, Rocky says, “I’m so pleased with hip-hop.” But he doesn’t believe he’s influenced by anyone else. “I pay homage, but I’d never go to my contemporaries for ideas.” Rocky prefers to listen to the “Renaissance masters, old dead motherfuckers.” When I ask whom he studies, he says, “I don’t study anyone. I study my own craft.” Then he contradicts himself, reeling off a list of countless artists, including Tupac Shakur, Wu-Tang Clan, the Fugees, Three 6 Mafia and DJ Quik. “Shout out Suga Free!” he yells, animatedly name-checking the slick, mustachioed MC who used to work with Snoop Dogg. “How the fuck you know that motherfucker?!?” he asks, when I nod. He’s not mad at me. He’s goofing. Again, complicated. Again, charming.

It’s late now, and Rocky is done. He bends his knees and spins around on his skateboard. Faster and faster, closer and closer to the ground. He stops, loses control, then smacks into a wall. His publicist can’t watch. “I’m dizzy as fuck!” he says laughing. Just before he hugs everyone, I’m offered an attempt on the skateboard, but I travel inexplicably backward. Perhaps my lean is way off, or perhaps I just don’t want to die yet. So I disembark. It’s hard rolling like A$AP Rocky, but he makes it look so easy.

A$AP Rocky headlines the Theater at Madison Square Garden Sept 22 at 8pm. $55–$95.