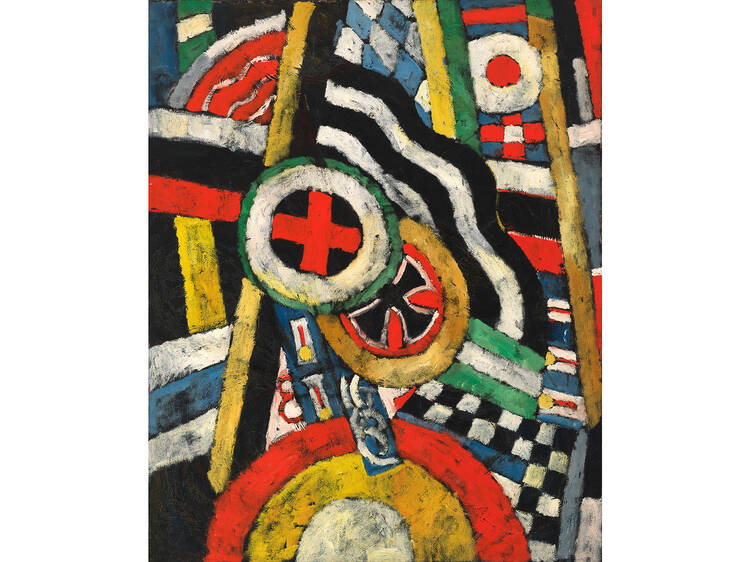

1. Marsden Hartley, Painting, Number 5, 1914–15

Photograph: Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art

The Whitney Museum is named for Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the Gilded Age heiress who, in the first decades of the past century, began to devote herself to the then-quixotic mission of promoting American artists. It is that mission which continues to distinguish the Whitney Museum—NYC's top art museum for American art—from the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim and even the Met. Its collection tells the story of modernism’s growth in America, and more indirectly, the tale of a country evolving from provincial backwater to superpower. Both can be seen in this list of the nine best examples of work from the museum’s permanent collection of paintings, sculptures, photographs and drawings.

RECOMMENDED: Full guide to the Whitney Museum in NYC

The Whitney is pretty much Edward Hopper central, with a dozen or so of his works in its holdings. This painting, created late in the artist’s career, is one of his most iconic. The stark nakedness of the figure, plus the louche details—the cigarette in the subject’s hands, the kicked-off high heels under the bed—provide vague hints of a walk-of-shame backstory, while the fall of bright light in which the model stands seems to deliver redemption and harsh judgment at the same time. The alienation and resignation pervading this scene—the sense that in America, you are nakedly on your own—is Hopper at his best.

Photograph: Courtesy Whitney Museum NY

Searching for the best New York museum exhibitions and shows? We have you covered.

Discover Time Out original video