Like a man living in his own personal Aaron Sorkin movie, Vin Diesel threw aside his teleprompter at last week’s CineCon in Las Vegas to deliver a spontaneous cri de coeur about the value of cinemas. His audience was America’s movie theatre owners, there to scope out what much-needed ‘product’ Hollywood has for them in the year ahead.

‘You guys don’t give a shit about the teleprompter,’ he grinned. Instead, Diesel waxed lyrical about his upcoming Fast X blockbuster and his pet subject: family. Cinemas were part of his Fast family, he said. They were the reason his megabucks franchise has been a success, and he knew what they’d been going through since the pandemic. ‘I look out and see soldiers on the front lines,’ he told them.

Five thousand miles away, his words would have been ringing painfully true. There, the acting CEO of England’s Tyneside Cinema, Simon Drysdale, has been emerging from the horrors of a redundancy round. Bankruptcy looms for Newcastle’s beloved cinema. A fundraiser has been launched in a bid to galvanise the locals.

‘We’ve got months to survive,’ Drysdale tells Time Out. ‘We’re 40 percent down on attendances from pre-pandemic and our costs are stratospheric. We were struggling pre-pandemic, but the situation is pretty dire now.’

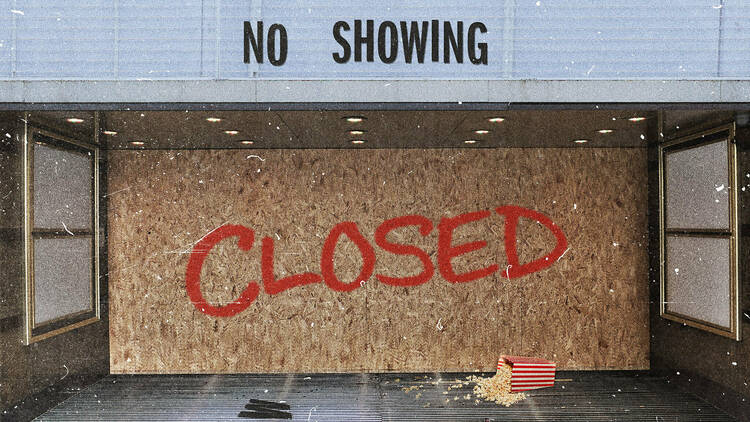

Tyneside’s woes are a worryingly familiar story two years on from the pandemic. Edinburgh’s Filmhouse, Aberdeen’s Belmont Filmhouse, Los Angeles’ Cinerama Dome, and London’s multi-arts space Riverside Studios have all either gone under or face closure.

‘Every theatre matters,’ he argued, ‘every theatre bears the traces of all the people that have come together to watch a Lubitsch silent, a Souleymane Cissé classic, or the latest film from Paul Thomas Anderson or Alice Rohrwacher. Just think of all those convocations of film lovers, sitting under the light of the projector beam.’

If you love cinemas as much as Marty, it’s a worrying time.

The new normal

Two years on from the end of lockdown, cinemas are grappling with a tough new reality. After a bonanza 2019 – the best year for cinemas since 1971 – ticket sales are down by more than a third around the world.

Streaming is hardly a new development but the prevalence of home-viewing options isn’t helping. Neither is a global shift to flexi-working. Like pubs, bars, restaurants, music and comedy venues, cinemas are losing vital after-work footfall. A pint and a ticket to Evil Dead Rise has become an Uber Eats order and a half-watch of Love is Blind. ‘Fridays are really quiet for us now because we’re in the city centre and people are working from home,’ notes Drysdale.

A pint and a ticket to Evil Dead Rise has become an Uber Eats order and a half-watch of Love is Blind

‘I understand that everyone is trying to make as much money as they can,’ says Walker-Hebborn, ‘but distributors are not keeping up their end of the bargain. They’re charging us 50-55 percent for mediocre films.’ The shrinking window between a movie’s big-screen release and the date it’s allowed to go onto a streaming platform continues to bite, too. ‘We’ve got people coming in and saying: “Is this a Disney film? I’ll wait for it to come on Disney Plus.’

Adapt or die

Box-office smashes like Top Gun: Maverick, Avatar: The Way of Water and The Super Mario Bros. Movie and, soon, Vin’s Fast X aren’t always major drawcards for audiences at cinemas like the Genesis. For them, box-office salvation looks a lot more like Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson rowing over a Guinness in The Banshees of Inisherin or the Raccaconie-fuelled mayhem of Everything Everywhere All At Once.

Many more are needed.

‘There’s still a real gap for new arthouse [movies], which has a greater impact on independent cinemas like ours,’ says Alex Temesvari, the general manager of Sydney’s 90-year-old Hayden Orpheum Picture Palace. ‘We have to work harder than ever to get people into our venue, which is why we have diversified our offering as much as possible.’

For this grand old movie oasis on North Sydney’s bustling Military Road, that’s meant a return to its 1930s roots by firing up the cinema’s famous Wurlitzer organ to intro live events. Its moviegoers are now gig-goers too, with everything from rock concerts to operas on the programme.

It’s been a lifesaving shift and gives Temesvari confidence in the future for cinemas like his. ‘History is on our side,’ he notes. ‘Cinemas have survived home video, DVD, piracy, streaming and now a pandemic. The industry has had to change, but it’s resilient.’

A menu for ants

Not every indie cinema has a 700-seat auditorium with a stage. For others, adapting to the new reality has meant new membership schemes, cheaper prices like Genesis, poshed-up dine-in options and other canny ideas to entice moviegoers back. These days you need more than a movie, in other words, to get bums back on seats.

‘A cinema can't just be a four-wall box with popcorn and a movie anymore,’ says Michael Kustermann, chief experience officer at America’s Alamo Drafthouse chain. ‘You really have to be able to engage directly with your guests, and you have to create a bit more of a “total night out” type of experience.’

Alamo has been burning the midnight oil to make new releases more ‘experiential’. For Cocaine Bear, there were small dime bags filled with powdered sugar to sprinkle on donuts; Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania had moviegoers peering at specially designed half-inch menus through magnifying glasses.

A cinema can’t just be a four-wall box with popcorn and a movie anymore

The nostalgia trend is helping deliver audiences, too. Tyneside Cinema recently held its first The Lord of the Rings marathon and is putting on special screenings of The Big Lebowski and other classics with devoted fanbases built-in to coax locals back.

At New York’s Nitehawk Cinema, a showing of the Wachowski’s cult racing flick Speed Racer was so popular, two more screenings were hastily added. They nearly sold out, too. ‘We’ve increased the amount of repertory programming we do, with more 35mm film prints,’ says director of programming, Cristina Cacioppo. Drag shows are another new addition to the line-up at the Nitehawk’s two cinemas.

‘It is difficult to get people out for regular engagements,’ says Greg Laemmle, president of LA’s family-run Laemmle Theatres chain, ‘but event cinema screenings and things that can be billed as special have been fairly successful. We’re trying to make coming out to the movie theatre more special.’

For Laemmle, who would have been eagerly following Vin Diesel’s spontaneous CinemaCon address, the long-term prospects for indie cinemas hang on more than just the odd blockbuster like Fast X and Top Gun: Maverick. ‘We need more romcoms and more mid-level kid pictures,’ he says. ‘We need a little bit of everything. Sure, we need Top Gun: Maverick, but [it won’t get] people back into the habit of seeing six movies a year.’

Back in the habit

It’s tough on the front lines, but all the cinemas that Time Out spoke to for this piece stressed the same thing: time and patience are needed to reconnect old moviegoers with what Martin Scorsese memorably calls ‘sitting under the light of the projector beam’.

‘What the theatrical market is today is not what it’s going to be in three to five years,’ stresses Laemmle. ‘I think it will come back stronger. Whether it’s coming back to 2018/2019 levels, I can’t say for sure.’

At Tyneside Cinema, though, time is one thing they don’t have. What they need is more movies – and more moviegoers – asap. ‘I think cinemas can be around in ten years time – if people use them,’ says CEO Simon Drysdale. ‘A lot of people bemoaned Filmhouse’s closure but the question is: when did you last go? That’s what it needs.’

So, does Genesis Cinema’s Walker-Hebborn – a man with a quarter of a century’s cinema-running experience behind him – think his East London landmark will still be around in a decade? ‘There’s no reason why it shouldn’t come back. It’s still a relatively cheap night out, it’s a great community thing to do. People do love it, they just need to get back in the habit.’

The 50 most beautiful cinemas in the world.

The peculiar beauty of the world’s most remote cinemas.