With a new study revealing that 20 percent of teenagers use their phones in the cinema and the prospect of more Wicked singalong clashes ahead, are badly-behaved audience members putting us off going to the theater? Film writer Sean McGeady discovers that there’s more to the story than meets the eye.

Poppers, body paint, crying, singing, dancing, death threats and social disintegration. No, this isn’t a recap of your last birthday party. These are just a few of the talking points that followed the arrival of Wicked in November 2024.

When the eagerly awaited musical opened, one American cinema chain even went so far as to screen a 30-second PSA forbidding audience members from singing along. Many didn’t listen. Wicked fans wanted to wail and nobody was going to stop them.

Wicked became a seedbed for every type of modern disruption, from aspiring influencers filming themselves singing, tears of joy streaming down their phone-lit faces, to one moviegoer who found a new way to defy gravity: by taking a mid-movie bump of amyl nitrite. A post on X calling for Wicked attendees to show off their photos of the film garnered thousands of responses – equal parts joyous participation and righteous indignation. Cinema etiquette, it seemed, had reached a new low.

if i hear a single word when i watch wicked in theater, all hell will break loose. nobody wants to hear your singing. stay quiet.

— Wicked News Hub (@wickednewshub) October 6, 2024

In a world of crumbling social conventions and tech-enhanced self-obsession, it’s easy for cinema purists to cast themselves as the heroes, fighting silently in the dark against the villainy of blue light, chit-chat and chuckling. But what if there’s more to it than that? What if it’s not them, it’s us?

Silence or celebration?

Westerners tend to view the cinema experience through a culturally specific lens: we file into the theater in darkness, find our seat and sit quietly for 90-plus minutes. But this doesn’t accurately describe the experience worldwide. In fact, it doesn’t even align with the history of cinema in the US, which for decades thrived in more raucous environments such as nickelodeons, roadshows, drive-ins and grindhouses.

Patrick Corcoran recently stepped down as the Vice President of the National Association of Theater Owners (NATO), following two decades of fighting the good fight on behalf of America’s 5,500 or so cinemas. He’s keen to point out the difference between disruptive behaviour and behaviour that’s simply different from our own.

‘There is no one audience,’ he tells Time Out. ‘A lot of people, especially cineastes, say that being in a cinema is like being in church – you have to be reverent and attentive. Well, there are a lot of different churches, a lot of different denominations and a lot of different parishes, right?’

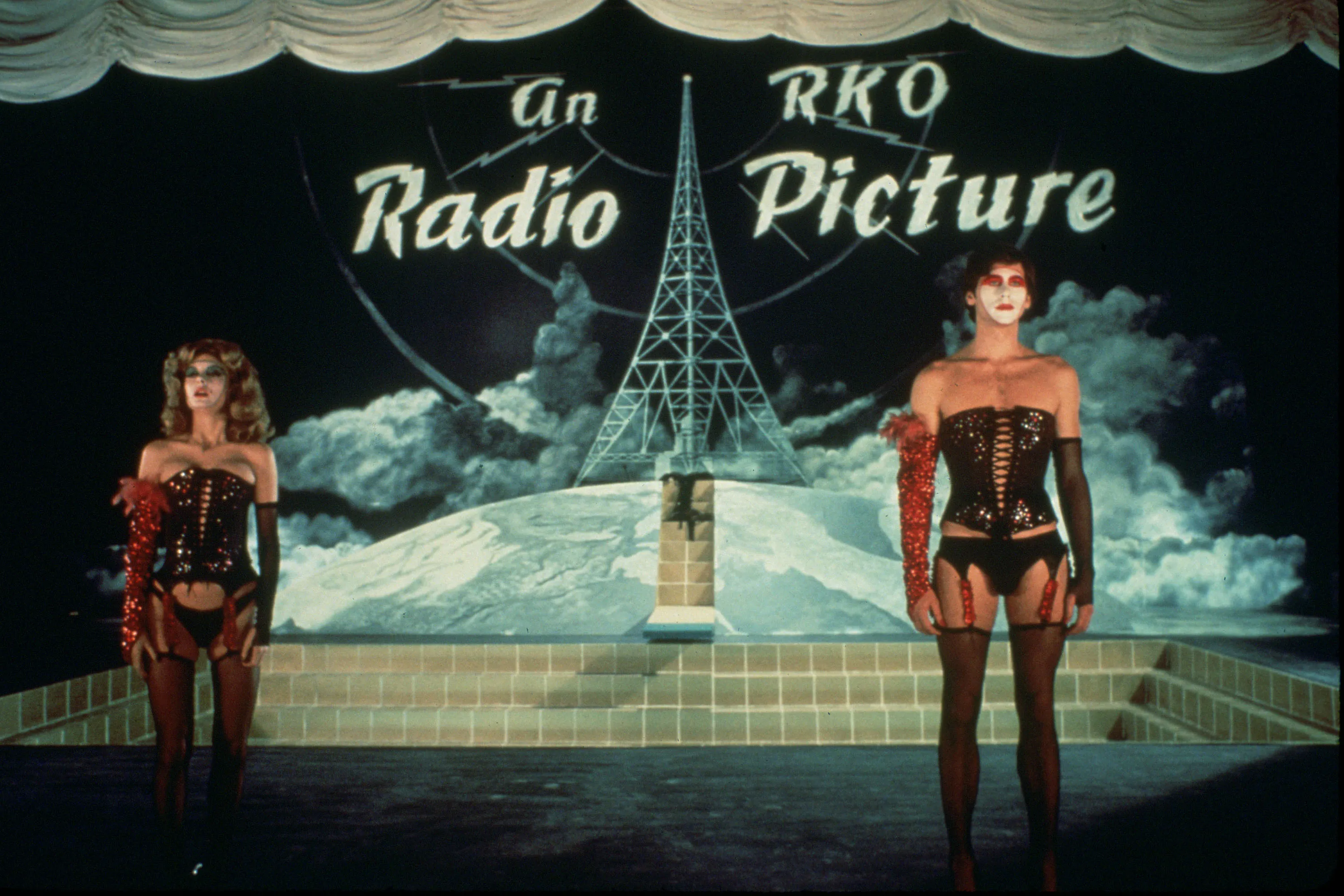

In India, rowdy crowds, call-and-response interaction and even singing and dancing in the aisles are much more commonplace than in the US. Around the world, participatory screenings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, complete with scripted callbacks and projectile props, still appeal to punters 50 years after the film’s release. And in pre-war Europe, many cinemas were working-class spaces where children ran amok and women peeled vegetables.

Over the years, the industrialisation of cinema has homogenised the theater experience, such that weird, wonderful, social screenings are rare outside repertory venues and grassroots film clubs. And when audiences do try to bend the rules to their liking, we’re quick to condemn them.

Singalong stress

The Wicked discourse has prompted fierce debate about whether there’s a place for audience interaction in the multiplex. Many fans wanted to sing along, and they wouldn’t get an opportunity to do so – at least, without reprimand – until Universal’s official singalong version hit theaters on Christmas Day, a month after the film’s initial release.

‘They probably should’ve done that at the beginning and not scolded the audience beforehand,’ says Corcoran. ‘There’s a way to accommodate what the audience wants.’

Boutique US chain Alamo Drafthouse did just that – eventually. ‘There were a lot of online rumblings around theater etiquette and we kind of followed that path,’ says chief marketing officer Chaya Rosenthal. ‘We realised that our guests were asking for [a singalong], and it’s just not like us to not create a custom [screening]. So we did it prematurely.’

Two weeks before the official singalong version hit theaters, Alamo launched its own. Rosenthal says the Wicked furore could have been avoided had fans had the opportunity to attend singalongs from the start. The debacle was an example of a studio failing to anticipate the wants of its audience.

‘It’s partly about theater owners making arrangements for people who want to participate in what’s going on,’ says Corcoran, ‘as opposed to just being the passive recipient of it. Both are valid. The problem comes when you have clashing audience expectations.’

Cell phone sinners

Most films don’t force us to contend with our neighbour struggling to hit that soaring E6 in ‘Defying Gravity’. We’re more likely to be disturbed by their phones. A new study from the National Research Group has found that 20 per cent of teens use their phones in theaters.

Here, clashes occur between the notions of cinema as a place of surrender and cinema as an extension of the home, where we’re free to behave the same way we would in front of the TV. The study also found that 60 per cent of teens use their phones while watching TV and film at home.

The problem, of course, is far from exclusive to young adults. Nobody is equipped to handle this technology.

‘We live in the most distracted time in human history,’ says Jay Van Bavel, professor of psychology at New York University. ‘Our brains did not evolve for this. The technology is incredibly recent and we don’t have the self-regulatory capacity to manage it very well.’ By carrying our phone-checking habits into the cinema, we risk breaking social contracts as well as our neighbours’ immersion.

We live in the most distracted time in human history

There’s a cost for phone users, too. ‘When we switch between tasks such as watching a film and scrolling Instagram, says Van Bavel, ‘memories don’t congeal in our hippocampus’. The more we divide our attention in the moment, the less we remember.

It’s worse if we’re not just consuming content, but actively producing it. TikTok is awash with videos shot during screenings: clips of movies; reaction videos; critical accounts of singing during Wicked; celebratory accounts of singing during Wicked…

‘Social media colonises our minds,’ adds Van Bavel. ‘Once you start thinking through the lens of creating content, you start filtering your experiences, looking for things to capture, rather than experiencing things more organically.’

However we justify whipping out our phone in the auditorium – whether it’s to check the time or surreptitiously capture a friend’s reaction to a film – it doesn’t make its light any dimmer.

No laughing matter

Expectations collide in subtler but no less upsetting ways too. At a recent screening of the 1968 film Whistle and I’ll Come to You, I was mortified when the freeze-frame finish sent a few of the 40-odd attendees into hysterics.

Their guffaws made me feel like an idiot – for taking it seriously, for paying attention, for feeling something. And that white-hot flash of shame quickly gave way to anger. ‘Why don’t they get it? Why are they even here? This is supposed to be for me!’

The popular idea is that ‘inappropriate’ laughter is derisive and comes from a place of irony. But is that true?

‘I don’t think people do it to be ironic,’ says Alex Powell (not his real name), a cinema manager who wishes to remain anonymous. ‘It’s behavioural responses, rather than people being like, “Let’s go watch the 1980s movie and laugh at it”.’

So what’s happening here? Much of it has to do with the changing language of cinema and the ways we remix, dismantle and discuss film online.

Because the freeze-frame has become so closely associated with the likes of The Breakfast Club, with a cheeky glance to camera and even with the ‘Roundabout’ meme, the device is now widely considered comedic. And if it’s used in a film such as Whistle, the contrast in tone is enough to trigger a reaction in some viewers that’s out of phase with others.

‘We’re now less likely to meet movies where they’re at,’ adds Powell, ‘and more likely to meet movies where we’re at.’

And where are we at? Memes are becoming the mother tongue of film discourse. And not just user-generated memes either.

Popcorn buckets, memes and milk

‘The memeification of movies is impacting the way we engage with art,’ says Powell. ‘Everything is presented to us with a level of levity now. With so many films, there seems to be a drive to find the moment [cinemas] can hang a social interaction on, and it’s usually based in humour.’

During Babygirl’s theatrical run, multiple cinemas made a show of serving milk. ‘This moment in an erotic thriller became a comedic device,’ he notes, ‘and that changes the relationship between the audience and the art.’ When distributors and cinemas amplify moments out of context, audiences anticipate them and become ‘Pointing Rick Dalton’ when they happen. Powell argues that it alters the audience’s reception of the film.

The experiential economy has had a huge impact on movie marketing, with theaters encouraged to ‘eventise’ films to shift tickets. That means custom drinks at the concessions stand, Barbie boxes and Nosferatu coffins in lobbies, limited-edition popcorn buckets designed to go viral, and more.

When cinemas encourage punters to snap photos and post on social media in the lobby, but forbid them from using their phones in the auditorium, is it any wonder that people forget that these spaces have different rules?

Do what the A-lister says

Audiences can only be expected to obey the rules if they’re made aware of them. Cinemas usually set such precedents using pre-film PSAs.

Alamo produces PSAs featuring big-name stars – if you won’t listen to an usher, one would hope you’d pay attention to Ke Huy Quan, Jamie Lee Curtis or even Godzilla. (Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande did a PSA for Alamo in October 2024, asking audiences not to talk or text during the movie; the former condoned singing a month later.)

The chain also taps into a more realistic deterrent than giddy threats of violence from Michelle Yeoh: shame.

In 2011, Alamo received a voicemail message from a disgruntled customer who was given the boot, and quickly turned it into a PSA. The implication is that, if you misbehave in an Alamo Drafthouse cinema, you could be publicly shamed too.

‘I see that point of view,’ says Rosenthal, ‘but the way I look at it is that, from a brand perspective, we care more about the experience than about what everybody thinks of us. I think it’s a strong statement of our priority: ensuring that all our guests can enjoy the film in silence and have an awesome experience.’

Connor Kirkwood is the Director of Theater Operations at the Hollywood Theatre, an acclaimed non-profit movie house in Portland, Oregon. For him, the wider audience experience takes precedence over individual customers too.

‘If it looks like someone is going to be a consistent disruption,’ he says. ‘We’ll say, “Hey, let’s get you your money back”. It communicates to them that you don’t want their business because it’s ruining the experience for your other [customers]. Most of the time their mentality is, “I paid to get in here, so this is my experience”. But if you show them you’re willing to part with the money in the interest of a greater atmosphere, most people are like, “Oh, I guess they’re serious”. And you won’t see those people again. And that’s great.’

Alamo Drafthouse pioneered the dine-in cinema experience (a type of disruption in itself, albeit one that its staff are good at minimising). But the call buttons and cards that audience members use to order food can also be used to complain about anything from the temperature to unruly attendees.

At Alex Powell’s cinema, staff intervene if they’re made aware of a disruption. But he also recognises that not every member of staff will feel comfortable doing so.

At Portland’s Hollywood Theatre, by contrast, there are no qualms about that. ‘I empower everyone who works at the Hollywood to give people a warning, to ask them to leave if necessary and, if it turns into something and I’m not there, to give me a call,’ Kirkwood says. ‘I’m a large man with a loud voice.’

We’re less likely to meet movies where they’re at and more likely to meet them where we’re at

In extreme cases, cinemas target whole groups pre-emptively. At the Alamo, for example, under-18s are denied entry unless accompanied by an adult.

Do these cinemas risk penalising – and alienating – younger audience members? ‘It’s something we have to balance,’ says Rosenthal. ‘We’re not as inviting as other theaters that don’t have age policies, but we prioritise the experience over the number [of customers]. It’s tough to say that from a marketing point of view, when my job is to get more people into the theater, but we have to be selective.’

For Corcoran, these countermeasures are self-defeating. ‘I understand the impetus for it,’ he says, ‘but it sends a signal that you are not welcome. It also punishes people who are not disruptive, just because they happen to be under a certain age.’

Adjusting expectations

There are many reasons why disruption appears to be getting worse – the erosion of social norms; technology hastening our collective individualisation; the sense of ownership that pop fandom instils in audiences; fewer ushers to impose cinema policies; increasing ticket prices fostering entitlement – and they’re all rooted in differing expectations of what the cinema experience is supposed to be.

Studios, distributors, marketers, theaters and audiences will never be on the same page there. ‘Most people don’t know they’re being disruptive,’ says Kirkwood. ‘They’re legitimately embarrassed when they have to be talked to. [My advice is to] try to create the right culture.’

There is no cinema experience without the audience

Fellow audience members may not be aware of the expectations we set for them. And everyone is participating in the same broken theatrical system, parsing the same mixed messages and living with the same social media addictions. The last thing anyone needs is someone else jumping down their throat.

‘There is no cinema experience without the audience,’ says Corcoran, ‘so I don’t think you can look at the audience as a problem.’

‘That’s part of the promise and the value of the moviegoing experience,’ he adds, ‘you give up to the movie. But you also give up to the reactions of the people around you. And you run into difficulties when you try to control them.’

Even if expectations still aren’t aligned by the time Wicked: For Good arrives in November, theaters should at least be better prepared to deal with the singalong crowd this time.