An anthropological museum set in 16 acres of landscaped gardens, which provides extensive facilities for families.

Photograph: Andy Parsons

‘I told you it was really steep,’ says Archy Marshall, better known as musician King Krule, with only the barest hint of satisfaction. The road beneath us seems to fall away. The Uber driver pauses at the top of the street, momentarily, before the car plunges down the hill into the south London twilight.

‘I love the hills around here,’ he says, as the rest of the city rolls out into the distance. ‘This area’s my favourite, the views… Go round a corner or up a road and you get these huge spaces opening up to you. It’s my favourite thing in London.’

We’re only travelling from one part of Forest Hill to another, but Marshall layers stories over even this short trip: that lots of gravediggers used to live in the area because of four nearby cemeteries, how his family history is tied to these streets.

‘This is the road my mum was born on, in… hang on… hang on…’ We pass a row of classic 1930s suburban houses and his finger hovers at the window. ‘That one. It was my great-grandparents’.’ Then he’s off again, telling us about him and his dad managing to drive up this 45-degree slope when it was covered with ice.

‘Because, like, my dad’s the best at driving and he’s got, like, a really good car,’ he jokes, mimicking the playground boasting he did as a kid.

This is typical Archy Marshall. He blends stories and history and pop cultural references. If you’d stumbled across him at our photoshoot at the Horniman three hours earlier, you’d have found him making up character sketches to go with the outfits the stylist picked out for him. A baggy pinstripe suit is rejected with: ‘I look like a creepy 1940s dude who’s about to marry his best friend’s daughter.’ ‘This is a bit “Clueless”, isn’t it?’ he says of a loud Alicia Silverstone tartan. A pair of flat-fronted trousers are modelled with a golf swing. ‘I like these,’ he says. ‘Because obviously I spend a lot of time on the green.’

Over his three albums as King Krule, his early EPs as Zoo Kid, and one album under his actual name, Marshall’s incorporated everything that surrounds him – and much of what’s inside him – to weave his own narratives. You can genre-spot, if that’s your thing. There’s a drift of late-night jazz, some of post-punk’s chiming instrumentation and arch vocal delivery, the kind of delicate psychedelia we do so well in this country, grime’s lo-fi FruityLoops futurism, stuttering punk guitars and hip hop’s love of the whole of the mix being greater than its parts. But there are scattered fragments of real life here too, stories from the city, stories from the sky. Marshall finds poetry in gazing upwards and inwards – as artists have for centuries before him – but also from the heartbreak chat overheard in the smoking area, like he’s borrowed London’s lighter and trousered it.

King Krule’s first full-length album ‘6 Feet Beneath the Moon’ came out in 2013, on his nineteenth birthday. Beyoncé shared a link to the song ‘Easy Easy’ on her Facebook page; Drake put it up on Instagram. He was approached by Kanye West to collaborate, but didn’t (‘I’ve turned down so many opportunities where I could maybe be rich by now,’ he told the New York Times). In 2017, there was ‘The Ooz’, which made it into numerous best-of-the-year, best-of-the-decade lists and was nominated for the 2018 Mercury Prize. This week, his third King Krule album, ‘Man Alive!’, is released. It’s less raw that ‘6 Feet’ and tighter than ‘The Ooz’, but it’s still cynical, still romantic, still pulling in musical ideas from across the world.

‘It’s just everyday kind of scenarios,’ Marshall says of the lyrics on ‘Man Alive!’. His speaking voice is as deep as his singing one, with the occasional south-of-the-river glottal stop. ‘I don’t think too conceptually and I write down what feels right at that moment in time.’

He often references cinema but uses films as a backdrop to his songwriting rather than inspiration. ‘Songs can be written in dark rooms with TV glare,’ he says, flagging track ‘Alone, Omen 3’ as an example. ‘It’s got nothing to do with “The Omen” but it was written in the presence of the movie,’ he says. ‘The plotline is that Damien [the devil’s son] becomes the president of America, so I thought that was fitting for the times…’

‘This jacket stank of shit, beer and piss, but my mum washed it and I feel safe wearing it now’

Whatever your feelings about horror films and the current president of the United States, or about Brexit (which Marshall touches on obliquely in the track ‘Supermarche’) he insists that ‘Man Alive!’ is not a political record. We’ve relocated to faintly bougie Forest Hill pub Watson’s General Telegraph. Marshall is drinking a hot toddy in an effort to warm up after being photographed in the relentless February drizzle. As the feeling starts to creep back into our fingers, Billy Bragg – with whom Marshall shares some similarities in vocal delivery – comes through the speakers, telling us that he doesn’t want to change the world and he’s not looking for a new England.

‘I just don’t talk about politics in a straightforward way,’ says Marshall. ‘I talk about myself sometimes. Individual people I talk about, my surroundings I talk about, the city I talk about, and the world and how it affects me… and I talk about it honestly, so I think that’s about as political as it gets. The observations have to coincide with current situations because that’s what’s affecting me.’

He finds the current state of the planet ‘quite alarming’, especially the ‘casual way’ in which far right-wing people have risen to positions of influence. He’s also aware that, as a 25-year-old Londoner operating in a creative field, there’s a danger of not being aware of anything outside your own little bubble.

‘You get lulled into a false sense of security,’ he says, as we sit indoors on a blue picnic bench. ‘The idea of socialism and the idea of social awareness and a welfare state: you think everyone’s on that same street, but they’re not. It’s dangerous… you don’t actually know what people think.’

He has been out of his south London bubble recently, though. Ten months ago he had a baby, Marina, with his partner, photographer Charlotte Patmore. Mother and baby are currently based in St Helens on Merseyside, to be closer to Patmore’s family, with Marshal shuttling between there and the capital. ‘It’s really interesting, it’s been beautiful,’ he says of fatherhood. ‘Having her has matured me and changed my life completely. I feel this energy that loves the world again… I always saw the beauty in despair, but I couldn’t always see the beauty in everything.’ He pauses. ‘She’s wicked, man.’

Spending time in the north west has also made Marshall re-embrace the simple joy of having a chat. ‘Up there everyone’s a lot more open and a lot more communicative,’ he says. ‘So when I come back down here, I can break down that barrier with conversation. I found the art in it.’

‘It’s a strong look, walking down the street, drinking from a Ribena carton’

A few weeks back, Marshall had to take a diversion around Waterloo station because of escalator engineering work and ran into a bandmate of his uncle’s, busking. She played him a Fela Kuti song, and, as he was walking away, the sound changed and degraded: he found it so beautiful he recorded it on his phone. He’s always sought out this kind of magic in the city. He comes from a family who are both hugely rooted in London and very creative. As a child he split his time between his father Adam Marshall, an art director and musician living in Nunhead, and his mother, Rachel Howard, a set designer and costume maker living in East Dulwich. His mother made one of the jackets he wears in our photoshoot – a boxy bum-freezer in an abstract black-and-white patterned canvas. The cloth comes from the backdrop to his stage set from when he was touring ‘The Ooz’. ‘It’s fire-retardant!’ he says, laughing and stroking the jacket as it hangs over the back of a pub chair. ‘It stank of shit, beer and piss, but she washed it and I feel safe wearing it now.’

He’s a natural archivist, and loves museums and libraries and keeping scraps of paper for the memories they provoke. He grins hugely as he talks about finding a note written by his father during the 1990s in a copy of Charles Bukowski’s ‘Ham on Rye’. He was delighted when his grandmother showed him a diary written by her father, a medic in the First World War. ‘The handwriting is beautiful,’ he says. ‘It’s tiny, precise handwriting; you can just about read it. And the way that he words things, there’s no melodrama, just like, “This is what’s happened.” I wonder if someone could do that with my stuff. I don’t know if I’m going to have an impact on the world. But I should probably start dating things.’

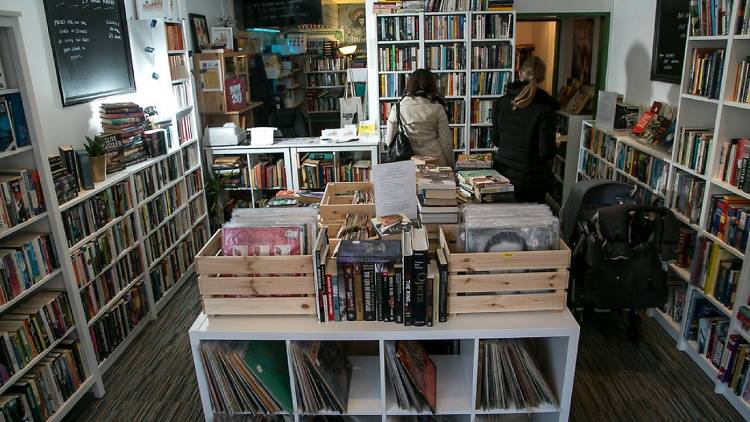

The Horniman Museum, where our day began, is ‘just a stone’s throw from where I grew up. It’s beautiful, really different and weird.’ But as with everything else, Marshall can see the troubling aspects of something he loves. Earlier, when we were taking pictures by its bandstand, bare trees framing a view of London, someone tried to describe the museum’s collection, searching for the right word: ‘“Ethnographic”? There are things here from everywhere.’ Marshall looked up. ‘“Colonial”?’ he suggested.

He’s not always serious. He loves Ribena, but never from a bottle. ‘It’s a strong look, walking down the street, drinking from the carton,’ he says with a topspin of irony. His earliest memories are of walking through Brixton in the summer, surrounded by city smells of McDonald’s and ‘dirt, pavements, sunscreen, hot dogs’. He talks fondly about his first flat away from his parents: friends staying nearly every night, but also sometimes being on his own and marvelling. ‘You could climb out the back window,’ he says, ‘and sit above Surrey Quays station.’

Marshall is always looking both up and down, talking about the London skies of his childhood (‘this deep grey-white that kind of lit up everything in a particular way’) but also about how he’s always ‘really intrigued’ by other people and ‘the mazes that lie beneath everyone’.

‘I always like social realism,’ he says. ‘But I prefer social surrealism.’

I say that that’s interesting. Can he define ‘social surrealism’?

‘You know me, I wouldn’t define that, man.’

‘Man Alive!’ is released on Fri Feb 21 on XL Recordings. Photography by Andy Parsons. Styling by Verity May Lane and Chloe Messer. Grooming by Yusuke Morioka at Coffin Inc. With thanks to The Horniman Museum