Ever changing, eclectic, irreverent and always one step ahead: in so many ways, David Bowie was the quintessential Londoner. His death this week sparked sorrow and tributes across the world but it was especially poignant for London. There was an impromptu street party in Brixton as heaps of flowers appeared at Bowie-related sites across the city. Tube staff, the Ritzy cinema and even the BT Tower paid homage. No wonder: he was one of us. This is the city where David Jones was born and raised, where he took his first musical steps, and where he became the artist, pop star and icon David Bowie. We know, because we were there.

The first issue of Time Out hit the streets in summer 1968, a year after Bowie’s debut album. The magazine and the singer emerged from the same London counterculture, and Tony Elliott, Time Out’s founder, remembers one of Bowie’s earliest gigs: ‘I trekked down to Beckenham with [future BBC star DJ] Bob Harris, who had been booked to play in a school hall. David Bowie, with very long perfect hair nearly down to his waist and wearing a floor-length dress, was the live act – just him and a guitar. I remember thinking: Oh, just another hippy folk singer.’

Bowie would eventually appear on nine Time Out covers throughout his career. This week’s issue of Time Out London is the tenth. With the help of some long-lost interviews from our archive, it’s our way of celebrating and remembering David Bowie the Londoner.

Young Dave

That story, as you’ll have read a billion times this week, started in 1947 at 40 Stansfield Road in Brixton where David Jones was born. Less well known are the facts about his family and upbringing that Bowie told Time Out’s Timothy White in a 1983 interview. His father had owned a wrestling club in Soho before getting a job at Dr Barnardo’s Children’s Home and meeting David’s mother, an usherette in a cinema. He’d also bought the future star his first instrument: a saxophone.

Although the family soon moved out to Bromley, the teenage Bowie regularly went back to Brixton: ‘It left great, strong images in my mind. All the ska and bluebeat clubs were in Brixton, so one gravitated back there. Also it was one of the few places that played James Brown records.’

‘As an adolescent, I was painfully shy’

David Bowie painting his flat in Beckenham in 1972 (Getty Images)

Beckenham and Glastonbury

By 1969 Bowie was playing his own songs as one of a loose creative collective – or ‘Arts Lab’ in south London. ‘The idea was to encourage people locally to congregate at this meeting house in Beckenham and become involved in all aspects of arts in society,’ he told us years later. ‘To come and watch strange performances by long-haired, strange people.’

In a Time Out feature in 1973, Bowie’s landlady and friend Mary Finnigan remembered the scene: ‘The whole of disaffected Beckenham, Bromley, Penge and points north, south, east and west dropped acid that summer.’ Finnigan, Bowie and his wife-to-be Angie helped organise a free arts festival at Croydon Road Recreation Ground, which inspired the Bowie song ‘Memory of a Free Festival’. (He’d soon get a bit less literal.)

Still a long-haired hippy singer-songwriter, Bowie played at the second Glastonbury festival in 1971. In a diary piece he wrote for us in 2000, he looked back at his 4am set: ‘All I can remember is staggering out of the Worthy Farmhouse at some ungodly hour. I had been ensconced in there for some of the night, drinking and smoking and such like. A mainly sleeping crowd gave me much encouragement as I fumbled through about nine songs. I accompanied myself on poorly played guitar and even worse Woolworth’s electric organ. All in all, a delightfully light and silly couple of days – all Tolkien and mushrooms.’

‘A sane man could go insane trying to pin him down’

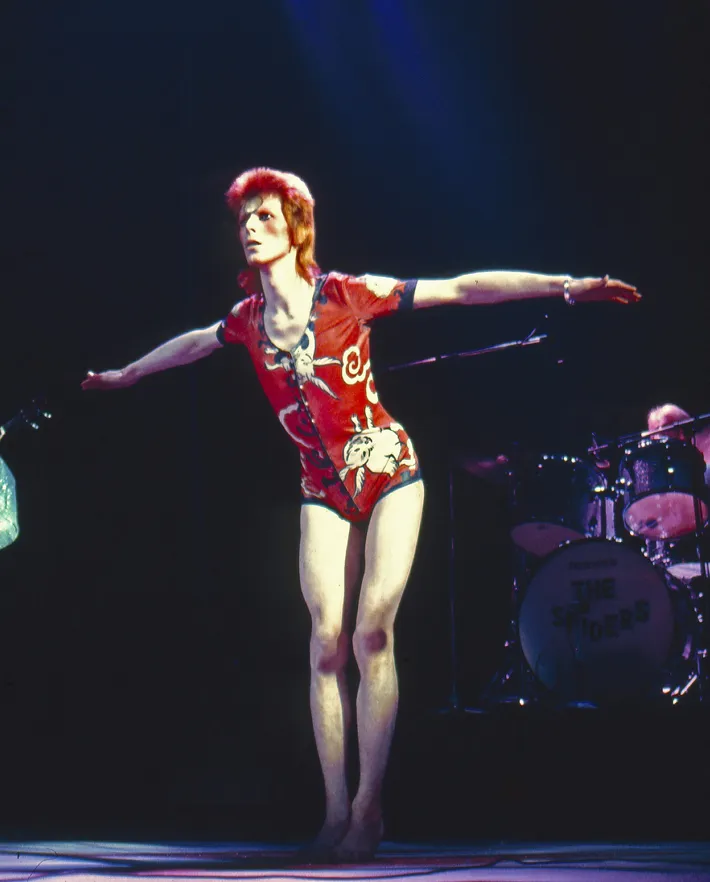

David Bowie in 1973 at the Hammersmith Odeon, where he played his last concerts as Ziggy Stardust (Ilpo Musto/REX/Shutterstock)

Becoming Ziggy

Despite achieving a hit with ‘Space Oddity’, Bowie’s first forays into music weren’t easy. ‘As an adolescent, I was painfully shy,’ he told us in ’83. ‘I didn’t really have the nerve to sing my songs onstage and nobody else was doing them. I decided to do them in disguise so that I didn’t have to actually go through the humiliation of going on stage and being myself.’ Soon the disguise turned into his first fully frmed character: the androgynous glam spaceman Ziggy Stardust.

On August 19 1972, our music editor Connor McKnight was at the Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park for a major date on Bowie’s ultra-theatrical Ziggy Stardust Tour. McKnight interviewed members of the audience, including Elton John (‘I just think he’s great’), Lou Reed (‘He’s got everything’) and Iggy Pop (‘I’ve seen Bowie naked’). In a feature in February 1973 – Bowie’s first Time Out cover – we gave our own awe-struck verdict: ‘A sane man could go insane trying to pin the fucker down. He is truly mercurial.’

Fame (and its downsides)

By 1975, the mercurial Mr Bowie was a major star with three superb hit albums: ‘Ziggy’, ‘Aladdin Sane’ and ‘Diamond Dogs’. That year he released the soul-influenced ‘Young Americans’ album, including ‘Fame’ with John Lennon: a bitter take on his new celebrity status. ‘We spent endless hours talking about fame,’ he told us years later, ‘and what it’s like not having a life of your own any more. How much you want to be known before you are, and then when you are, how much you want the reverse.’

‘That was the wipeout period. I was totally washed up’

The traps of celebrity included drugs: lots of drugs. Bowie appeared on our cover in 1976 as the thin, frail alien star of Nic Roeg’s film ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’. (He had to wear fake skin for the role: ‘a spermatozoon of an alien nature that was obscene and weird-looking. I think it was put together with the whites of eggs, food colouring and flour’.) At the time he was living in a rented house in Los Angeles full of mystical Egyptian decor.

‘That was the wipeout period,’ he recalled in our ’83 interview. ‘I was totally washed up emotionally and psychically, completely screwed up. I’d stay up for seven or eight days on the trot! By the end of the week my whole life would be transformed into this bizarre nihilistic fantasy world of oncoming doom, mythological characters and imminent totalitarianism. Quite the worst.’

Recovery

It took several years and another relocation – this time to Berlin – for Bowie to straighten up. For a six-page Time Out cover interview in 1983 – titled ‘The Man Who Fell Back To Earth’ – the 36-year-old Bowie was candid, healthy and full of beans, and dressed ‘like a librarian in crisp blue shirt, sleeveless argyle sweater and khaki slacks’: a far cry from his emaciated Thin White Duke character of the mid-’70s.

That look lived on, though – especially in London, where Bowie’s coke fiend-meets-‘Cabaret’ aesthetic had entranced the New Romantics who flocked to the Blitz club on Great Queen Street. Steve Strange, Boy George and Adam Ant led a new generation of mini-Bowies. A few lucky Blitz kids even appeared in his ‘Ashes to Ashes’ video after he visited the club in 1980.

Bowie’s gloomy Berlin era also loomed large over bands such as Joy Division. As Bowie told us, the production of ‘Low’ ‘coloured what was to happen in English music for some time. That “smash” drum sound, that depressive gorilla effect set down the studio drum fever fad for the next few years. It was something I wish we’d never created.’

Bowie at the movies

Instead of chasing his own tail with the new generation, Bowie threw himself into screen acting. He starred on two more Time Out covers in the process, including one as Vendice Partners, the smarmy ad exec he played in ‘Absolute Beginners’. Tragically, he turned down the chance to play a James Bond villain opposite Roger Moore and Grace Jones in ‘A View to a Kill’, but we did see him with mullet, magic orb and codpiece in Jim Henson’s ‘Labyrinth’. For some fans it was the end of Bowie: practically panto.

But Jareth the Goblin King wasn’t really all that far from Ziggy – and whether he was cast as a messianic Kiwi POW (‘Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence’) or a cello-playing vampire (‘The Hunger’) Bowie never really seemed to be playing anyone but himself. As Nagisa Oshima, the director of ‘Mr Lawrence’, told us at the time: ‘I have never thought of David Bowie as an actor, but just as a wonderful person – almost like an angel.’

Bowie at ease

In the ’90s, after his wedding to the supermodel Iman, Bowie reinvented himself for the last time: this time rocking a goatee as a genial elder statesman of music and art. When we caught up with him in 1995 he bigged up Damien Hirst and bantered with Brian Eno. (The lifelong friends exchanged emails right up until Bowie’s last week on the planet.)

Then there was the 1998 interview we’ll just call ‘David Bowie: The ISP Years’. Mr B had just had his teeth fixed, he told our interviewer, and got a job writing online book reviews. But more importantly he’d launched BowieNet, his very own internet service provider, and – ahead of the curve as ever – was brimming with enthusiasm for the world wide web: ‘I think, without knowing it, the internet was something I was always absolutely desperate to get involved with.’

To launch the new millennium, Bowie returned to Glastonbury for the first time since his lost weekend there in ’71. Ahead of his triumphant headline set he gave us an exclusive diary feature. It didn’t just track his rehearsal schedule: it also let readers in on his struggle to remember the lyrics to ‘Space Oddity’, his love of the TV drama ‘The Corner’ and his overbearing worry about what on earth to wear. (‘Being British,’ he confided, ‘the main thing on my mind is wardrobe.’) He was still a starman, but keener than ever to let us earthlings get close to him.

‘Get my fucking name right!’

David Bowie in Time Out London, 1998

When Bowie curated the Southbank Centre’s Meltdown festival in 2002, he gave us one last big interview – mostly, it seemed, so he could slag off the people who thought his line-up was too mainstream. ‘I want it to sell out: to be the most popular Meltdown ever,’ he grinned. ‘I’d put Shirley Bassey on if I thought it would drag in a few punters.’

The end

Meltdown was a rare homecoming. ‘I’ve hardly been in London in a social, living way for so long that it’s almost an alien city to me now,’ Bowie told us in that 1983 interview. After years of continent-hopping he had left the UK for good: moving to New York with Iman, raising his family, making music, retiring for a decade and – in 2013 – returning for two final LPs. It was in NYC that David Bowie passed away on Sunday, two days after his sixty-ninth birthday and the release of his twenty-fifth album.

‘Blackstar’ is Bowie’s legacy to the world: an incredible record with more force, wit and innovation than you’d hope for from any artist of his age – let alone a man suffering from terminal cancer. Although his death is desperately sad, we’d rather remember it as his final triumph. Who else could burn out, not fade away, at the age of 69? He even got the last laugh by following God on Twitter a few days beforehand: Pascal’s wager, 2016-style.

And though midtown Manhattan is a long way from Stansfield Road, we’ll let him off for his wandering too. As always, he had his reasons – and one of them was that after 40 years of fame, plenty of British fans were still mispronouncing his name. ’I know when I come out of my hotel [in London] there’ll be some fucker there with a camera,’ he told us in 2002. ‘“Oh look, it’s David Bauwwwie!” I want to say: “Look, you’re English, I’m English. Get my fucking name right!”’

Rock ’n’ roll (not to mention sex and drugs) took the boy far from London, but nothing ever took London out of Bowie. We’ll miss him. He inspired thousands of artists. He gave misfits and weirdos everywhere the courage to be themselves – to be heroes, if you will. He was the man who changed the world: not bad for a skinny boy from Brixton. And now he’s gone, there’s only one thing to do. Let’s dance.

Inspired by Bowie: 101 people who owe a debt to Dave

Illustration: Bryan Mayes

Illustration: Bryan Mayes