An unforgettable window into the seminal moments of a nation by one of theatre's living legends.

Excerpt from review by Tim Byrne:

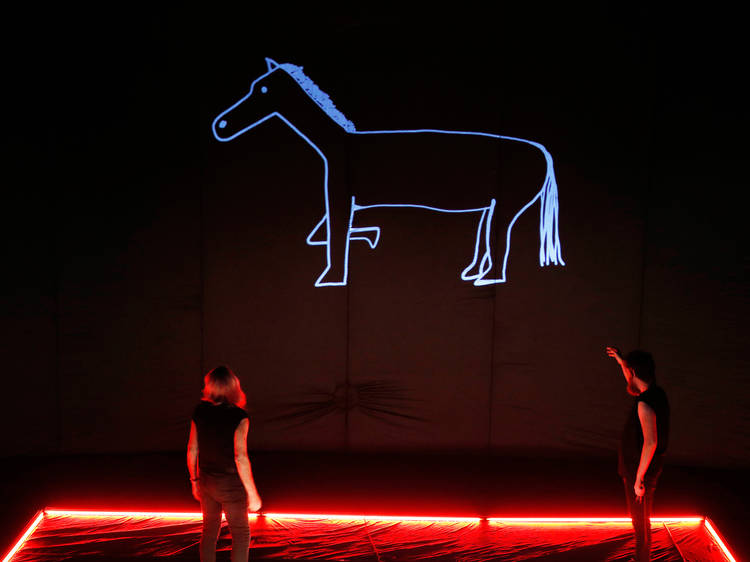

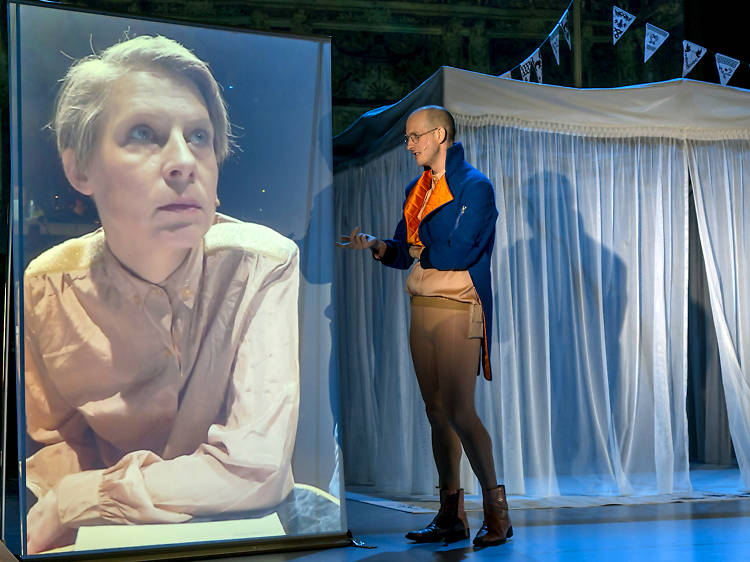

Of all the art forms, theatre is the most ephemeral; once that curtain comes down, the only place a production exists is in the audience’s memory. French Canadian theatre maker Robert Lepage and his company Ex Machina return to Melbourne with a project dedicated to memory, both personal and collective.

887 is an autobiographical one-man show – the title is the address of Lepage’s childhood home – but it is also a beautifully considered evocation of a seminal moment in the history of Québec: the October Crisis of 1970, when the Liberation Front of Québec kidnapped and murdered cabinet minister Pierre Laporte in a bid for French Canadian sovereignty. Lepage was 12 at the time, but some memories are hard to shake.

Read the full review.