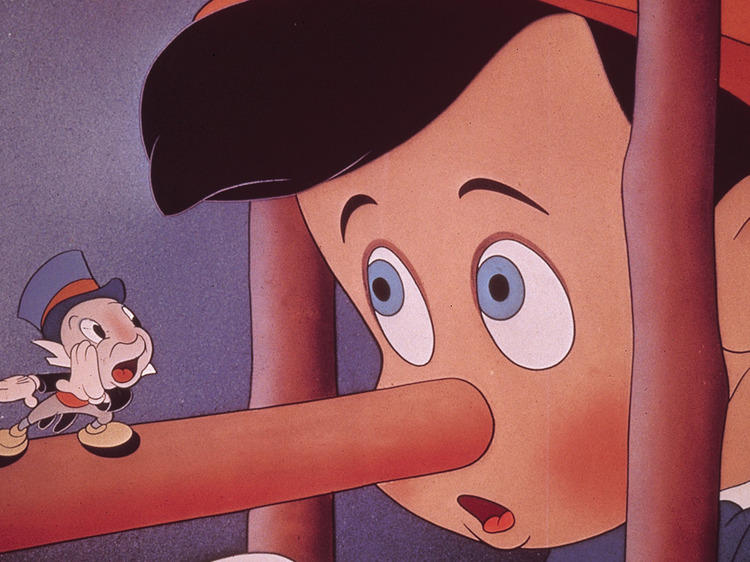

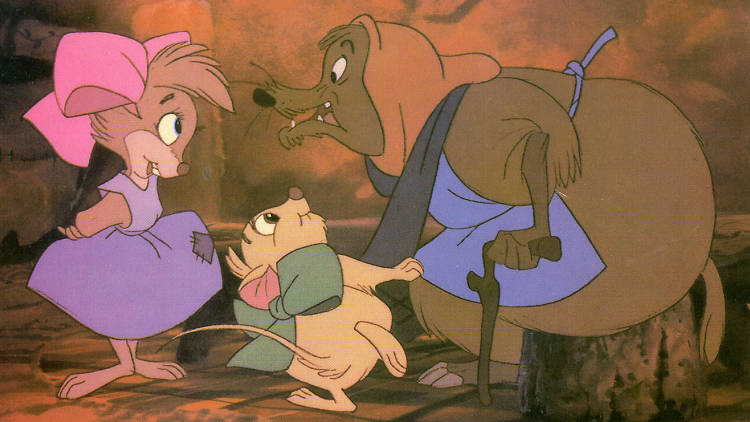

A wooden puppet yearns to be a real boy; he must prove himself worthy.

Directors: Ben Sharpsteen, Hamilton Luske, Bill Roberts, Norman Ferguson, Jack Kinney, Wilfred Jackson and T. Hee

Best quote: ‘Always let your conscience be your guide.’

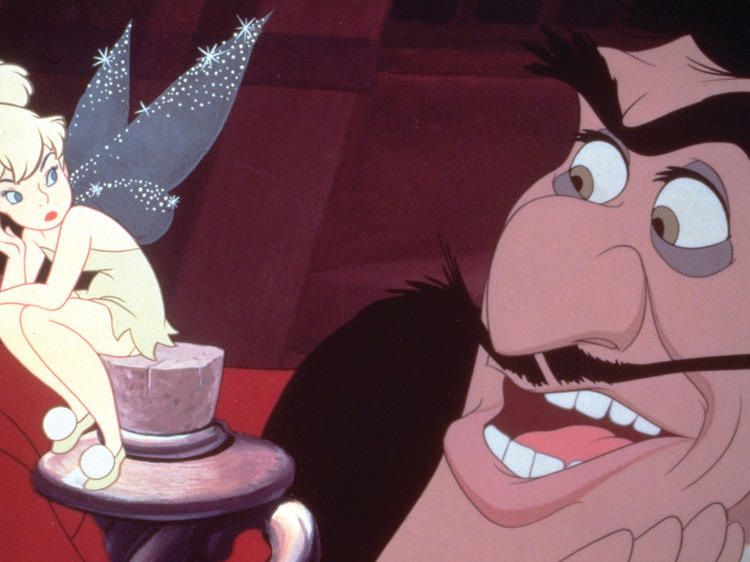

Defining moment: Playing pool, drinking beers, smoking cigars: Who knew it could transform kids into jackasses? (Literally.)

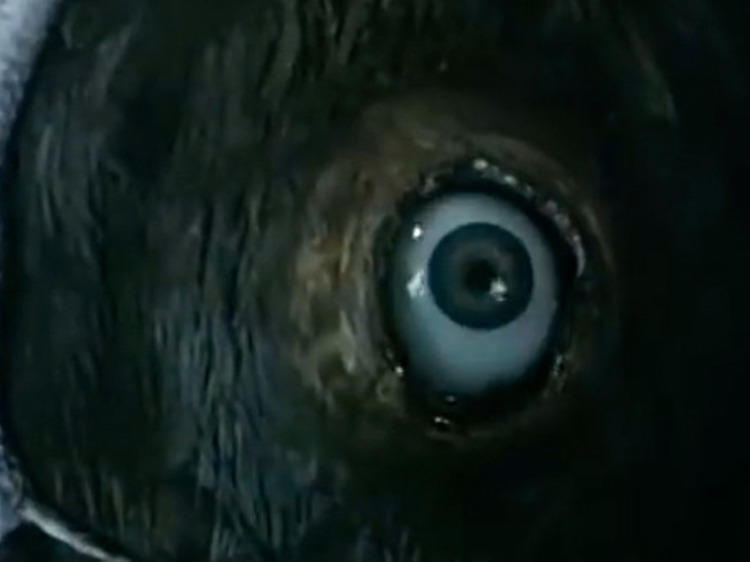

Pinocchio is the most magical of animated movies, a high point of cinematic invention. Its influence on fantasy is massive: Steven Spielberg quotes the soaring ballad ‘When You Wish Upon a Star’ in his dream project Close Encounters of the Third Kind (and remade the whole picture with his aching robot-boy adventure, A.I.). Disney’s second feature – originally a box-office bomb – begins with a sweetly singing cricket, yet plunges into scenes from a nightmare: in front of a jeering audience on a carnival stage; into the belly of a monstrous whale; beyond all human recognition. (Pinocchio’s extending schnoz is animation’s most sinister and profound metaphor.) It’s staggering to think of this material as intended for children, but that’s the power here, a conduit to the churning undercurrent of formulating identity. The takeaway is hard to argue with: Don’t lie, to yourself or others. Cultural theorists have, for decades, discussed Pinocchio in psychosexual terms or as a guide to middle-class assimilation. But those readings are like cracking open a snow globe to see that it’s only water. A swirling adventure flecked with shame, rehabilitation, death and rebirth, the movie contains a universe of feelings. Pinocchio will remain immortal as long as we draw, paint, tell tall tales and wish upon stars.