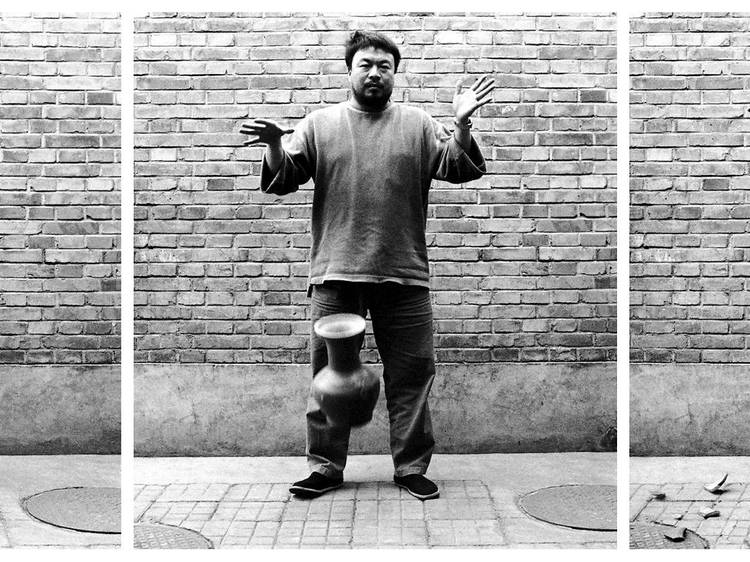

© Ai Weiwei

Ai’s most provocative early work sees him let a two thousand year-old pot fall slip from his hands and shatter to pieces on the ground. In Miami earlier this year an artist made their own protest by dropping one of Ai’s appropriated pots.

Ai Weiwei interview: 'I don't think I'm that important'

Since his release from detention in 2011, artist Ai Weiwei has been barred from leaving China. But that hasn’t stopped him from becoming one of the most famous artists in the world. On the eve of a London show, Time Out visits him to discuss surveillance, success and staying visible

There are no police officers outside Ai Weiwei's grey brick studio when Time Out visits him on a chilly Beijing morning. This is a noticeable change. Until recently, the plainclothes officers parked continuously outside Ai's studio on the outskirts of the city were as constant a presence as the cats roaming his compound and the flowers he places in the basket on a bicycle out front every day, a subtle form of protest on Ai's part that represents his lack of freedom to travel abroad or show work in China. He still does not have his passport. Yet, while the authorities have tried to make Ai invisible inside China, the artist has responded by maintaining a high profile on the international scene. He's currently the subject of a major retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum. He's also managed to keep up a non-stop social-media presence, even popping up recently in a selfie with US lifestyle guru Martha Stewart. This week, a show of his new works opens at the Lisson Gallery. We asked Ai about how he squares his roles as dissident and art star, and how this paradoxical situation has informed his latest output.

Your new show focuses on objects such as gas masks, handcuffs and bicycles. What's the connection between them?

'These are mostly objects that relate to my small world. For example, the "Forever" bicycles [pictured, right] were a brand from when I was growing up. In our village there were no real roads and we always had to ride bikes to carry things. I thought they would be good for a public sculpture because people relate to bikes. They're designed for the body and operated with your body. There are few things today that are like that.'

Do you miss being able to visit London?

'I miss London. London is what we can really call a civil society, which is a term you cannot even mention in China - they think that's some kind of dirty word. British culture today is very sophisticated. I enjoyed every minute when I was there and hopefully one day I can visit again. Especially after I was released from detention, I was so touched and shocked to see people in London and in the art community giving such support. They openly confronted my condition and really supported freedom of speech. I think sensing that made my personal condition become acceptable.'

How do you manage the installation of your work when you can't be there?

'I may not be the best artist, but I really am the best remote-control artist. I use the internet, Skype and communication of all kinds. I've done dozens of shows without being there because I still communicate with the organiser and the viewers.'

Do you think the Chinese authorities' attitude toward you has changed?

'They're much more open towards me and much more relaxed. Nobody follows me if I go out - there's no car outside. I can travel within China quite freely and nobody says: "Where are you going?" They've given me maximum freedom, I should say, to do my work and even talk to you. So I consider that a very friendly attitude toward me.'

Have they tried to restrict your art?

'No. They've been very clear in that sense. Although I don't think they're really satisfied with the result. They think there must be some kind of meaning there or some kind of conspiracy behind it.'

Do you see your art and activism as separate?

'No. My activism is actually only for my art, for my essential rights. To protect those rights, I became a so-called activist. It's inseparable from my art. Art needs protection; freedom of speech needs protection. Through art I make the argument and through my argument I may make art.'

Do you worry that by being such a high-profile artist and activist you might overshadow those who don't have the kind of voice you do?

'I think this is a world with competition. Even for freedom, there's still competition. I don't think you can really overshadow a voice if that voice has an idea behind it. I didn't even know I was an international celebrity [for a long time], because in the years I became famous, I wasn't out in the world - I was here [in my studio]. I told the authorities that they've made me much more popular in the past few years.'

Do you think you've become more popular in China as well?

'Much more. Mainly with people who can get information from outside and who can get on the internet. I think it's more with young people. They just don't understand why I have to be punished like this. A lot of people think there's no possibility [of change] here, but I'm a little bit naive. In the evening I become so desperate and disappointed, but in the morning I'm refreshed again.'

You can now buy Ai Weiwei mobile phone covers, umbrellas, and any number of other products. How do you feel about this commercialisation of your image?

'I have no problem with people using my image as long as it carries symbolic meaning. Of course I hate things that aren't done well, that are trash or crap, but in my position I can't really control that, even if I wanted to.'

You run a large studio and much of your work is outsourced to craftspeople.

Do you worry about your art becoming impersonal?

'No. I hope my work can be as impersonal as possible because I don't think I'm that important. I'm the one who initiates it, who guides it, and is controlling the idea, but I don't care if it's mine or not. People have too many fantasies about what art is about. Art is about ideas, about decisions, about expression and about communication. I'm really good at expression and communication. Andy Warhol is a perfect model for me.'

If your work's about communication, then do you see your internet presence as an extension of your art or a possible replacement for it?

'Actually, the internet is not an extension of my art; my art is an extension of the internet. If there's no internet, there's no Ai Weiwei of today. I'm a pure product of the internet.'

Read more art interviews

Discover Time Out original video