This show has been three years in the making. How long do you spend on one painting?

‘It’s really hard to quantify how long a painting takes. I work in series now as I find it helps me think on different subjects as I can become too obsessive. Sometimes it can take a month and other times longer, like two works in the show, which took three years.’

Animals are a constant in your work.

‘Actually this show is quite monkey heavy.’

Why is that?

‘I’m not sure I can fully articulate why I’m fascinated by monkeys. They are so “other” but they are also really human. In the work they represent our creature reality, I love that phrase, our “animal nature or our “animalness”.’

Although the paintings are exceptionally contemporary there is traditionalism to the format of portraits, landscapes, and still lifes as well as a hint of northern renaissance otherworldliness. Are you a fan of Hieronymus Bosch?

‘I love Bosch. I do see elements of still life, portraiture and landscape in all of the works but I come from the approach that genre is very fluid and can be collapsed at will. Each painting escapes easy categorisation, so a portrait isn’t straightforward portraiture, there are elements of a state of mind I’ve experienced. I also consider the paintings where a figure isn’t present to be portraits, but portraits of a psychology, a neurosis, or our desires. One of the joys of painting is that you can reference all of these art historical riches but you can interpret them in a contemporary context. A great subject of the work is the celebration of painting now. I think there is something really profound about using a medium that has supposedly been dead for 150 years. It’s a metaphor for something that is eternal and remains despite everything.’

Your figures have an androgyny to them, are they influenced by anyone?

‘All the portraits reference a close friend who went through gender reassignment; he has become a very important figure of inspiration for my work. It prompted me to think about identity and how we see ourselves beyond gender. I’ve always identified as a feminist and I’ve included some books by Judith Butler in the library space at the gallery. I find her very inspirational as she talks about how gender is something we perform and is malleable. When this happened to my friend, it stopped being theoretical. I hadn’t realised how labyrinthine sexuality is. It really affects our psychology as well as our physicality. So the face becomes a device on which I hang all my investigations and concerns about our social ideas.’

'I find sunken eyes very beautiful'

Why do your figures always have exceptionally sunken eyes?

‘Personally, I find sunken eyes very beautiful – it’s the most erotic zone of the body. I discover beauty in places that aren’t necessarily conventional but I also use it to hint at a sort of interiority that the viewer might wonder at.’

The title of the show is inspired by a Wallace Stevens poem, ‘Fabliau of Florida’. Can you tell us more about the influence of his work?

‘It’s quite a short poem. The beach scene in Florida really stands out, where the overcast sky, surf and the sand become indistinguishable from each other. For me it celebrates liminality and the fact that these thresholds are hard to separate, which is something that really runs throughout the whole show.’

There are certainly many unlikely scenarios in your paintings. In ‘Hedgerow Living’ (pictured above) one of the animals hairline becomes the outline of three monkeys…

‘I’m glad you saw that because sometimes I wonder if I’m too subtle. What you’re looking at is a squirrel whose tail descends into these monkey creatures and there is a rabbit who is in the process of blowing away and as that’s happening its been coiffured into these monkeys. I suppose at that point I was thinking about aspiration and desire for something that is exotic or something that is transcended above the mundane and the everyday.’

Is there any symbolism in the rabbit and the squirrel?

‘Only in that they are really prosaic animals, they’re vermin.’

In ‘Elimination of a Picture’ (pictured below), there is a strange animal that looks like a lizard that has amazing scales.

‘It’s a Pangolin and each scale is made of keratin, you know like our hair, It’s the only creature on the planet that exists like that. It’s a really ancient species but it’s endangered because it’s delicious [to eat].’

Really?

‘Yes, it’s virtually extinct so it’s really important that we try to conserve it. Again I chose it as it’s a perfect metaphor for vulnerability because it’s so endangered but it’s got this incredible armour. It’s a dinosaur really, when it rolls up it’s impenetrable. It’s an incredible creature.’

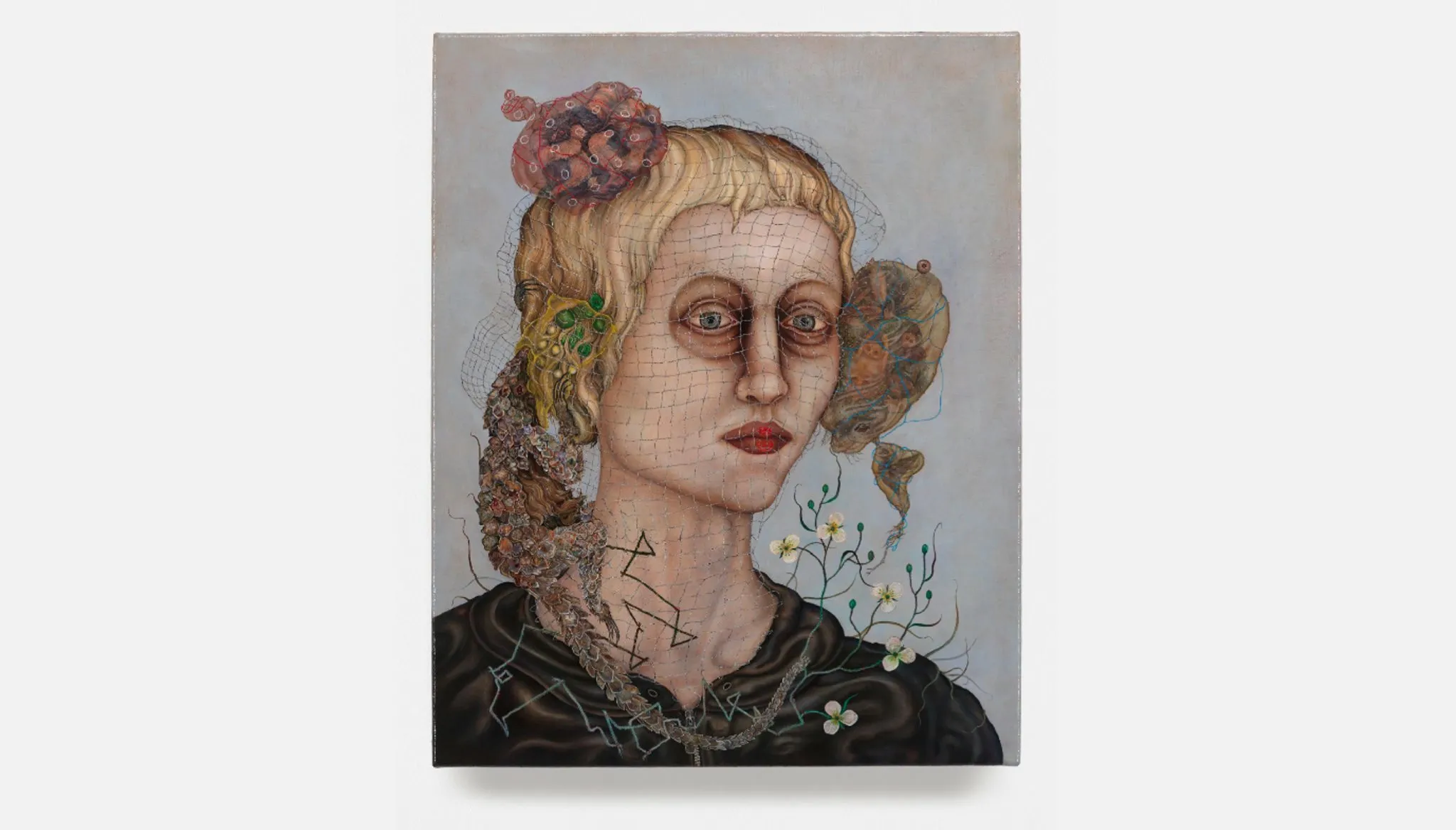

Apart from animals, another visual trope you use in ‘Elimination of a Picture’ is netting, which seems to encase the figure.

‘Yes, is it protection or a fortress or an ambiguous veil? The painting’s title actually comes from Richard Dadd’s poem. One of my favourite paintings of all time is his “The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke” – there’s something about it which is so authentic. It’s not fussed with what’s good taste or what’s art and it’s focused on a personal vision. I suffer from horrendous panic attacks. When they happen it’s almost as if time and rational thought are suspended and I have a real appreciation of my physicality and my “creatureness”. Although they are a real problem, the silver lining is that they’ve given me this insight to the work of Dadd or Swiss artist Adolf Wölfli. I’m drawn to work that comes from a place of struggle.’

What does the flower necklace represent?

‘The flowers are not entirely what they seem. They look beautiful and seductive but they are incredibly deadly. On an aesthetic level they come from something that is very organic that joins on to a very geometric stem. Throughout all the work there is an idea of how nature is treated, and how it has been interfered with.’