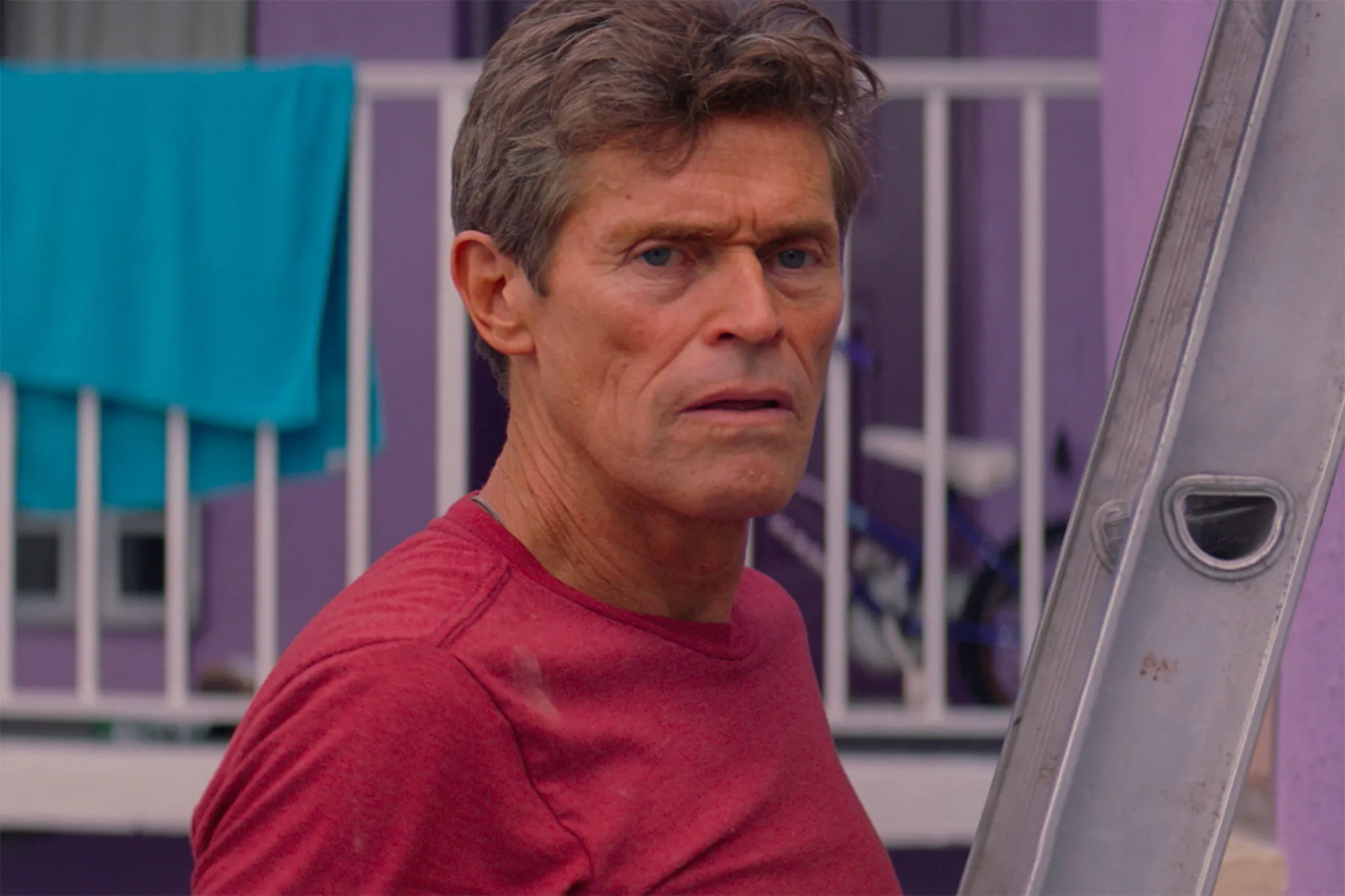

Willem Dafoe suffers magnificently. It’s his thing, suffering. Be it under the harsh glare of Lars von Trier in the brutally violent Antichrist or under Madonna’s dripping candle wax in Body of Evidence, Dafoe has put up with a lot of shit. The actor, 62, is gifted with the ability to always seem vexed; he has let his directors use that for laughs, as Wes Anderson does, or lent instant grandeur to superhero movies. (Dafoe is about to start work on Aquaman.) But this longtime improviser may have landed his most tortured role yet in The Florida Project, Sean Baker’s unflinching follow-up to his iPhone–shot indie debut, Tangerine. In the new film, which makes its Stateside premiere at this year’s New York Film Festival, Dafoe plays the manager of a scuzzy motel outside Disney World. From so humble a part, Dafoe is able to mine crankiness, compassion, confusion and, perhaps, may get himself a gold statue for the first time. Not that any of that awards talk fazes him. While Dafoe laughs easily during our chat, he'd rather talk about the essence of what he does best: disappearing.

Bobby, your character in The Florida Project, is a building manager but also, occasionally, a protector of young kids who live in tough circumstances.

I like where he’s placed in that world. Bobby is with them, but he’s also outside—he’s in and he’s out. There’s nothing particularly extraordinary about him as a person, but there’s something beautiful about how he’s a regular guy that does heroic, small things.

As much as the movie sometimes seems like a wonderland for these kids, we know better when we meet their parents.

You have the kids’ world, which flirts with chaos and imagination and is pure fun and irresponsibility, and that’s played against some very hard realities. To be a go-between between those two worlds was a privilege.

The Florida Project

The role gives you many moments to improvise. You have a glorious little aria on a balcony, just smoking and thinking.

That’s really about Sean [Baker] saying, “I want to see something from Bobby, we’ve got good light. Can you go up to the second floor? Does someone have some cigarettes?” It’s very fluid. I knew there would be a kind of looseness working with him.

Some of Bobby’s anxiety seems to directly reference your iconic performance as Jesus in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ. How closely does that film follow you around?

I think it was key. So much was required of me. Actors want to be challenged, to be put in a position where the heat is turned up. And we had a master filmmaker. Look, it was a low-budget movie. People forget that. We were healing the blind in the afternoon and up on the cross in the evening. That’s not a complaint—it was kind of a blessing.

Every time you’re in a Wes Anderson movie—and I count three of them so far, once with you playing a rat—it must be a completely different experience from an improv-heavy gig.

Yes, it’s the opposite. With Wes it’s about perfecting the gesture. And often the gesture is decided beforehand. For The Grand Budapest Hotel before we started working, Wes showed me a line-drawing animatronic of the whole movie. And it was fantastic! He did all the voices. I said to him, “You don’t have to make it—just release this!” And he told me, “Some actors don’t want to see this, because they don’t want to hear me say their lines.” But I love that. I believe in imitation. I believe in working from models. It’s a place to start. It’s a language. You breathe life into it.

Where did you learn that? Sometimes your acting feels like flirting.

Nobody flirts anymore! They’re flirting with themselves [looks down at imaginary cell phone in hand]. This is a mirror. One of my favorite things to do is walk on the streets of New York. Yes, I get some attention because my work is in the public. But that’s not what I’m talking about. I like seeing all the people, seeing survival strategies, fashion strategies, gender strategies. That gives me hope. But when I see everyone on their phones, my heart sinks.

You live in Rome these days with your wife [the Italian director Giada Colagrande]. Do you still feel like a New Yorker?

I identify very much with New York. My adult life really began here. I was the grand old age of 22 when I moved here. It was a great time because it was 1977. The city was a mess. Those were the “Drop Dead, New York” days. Punk was established but lots of things were changing. You’re a young guy, you’re not worried about tomorrow, you’re living downtown in some funky neighborhood. It’s affordable. You’re not thinking about a career—you’re thinking about getting together with some friends and making something that’s cool. When you grow up in the Midwest, you have no relationship to this idea of being an artist. Then you come to New York, you’re living with poor people, people slipping through the cracks. It radicalizes you. You see differently. You start identifying with artists on the margins of society. It’s dynamic.

Dafoe in The Florida Project

Your work always feels rooted in a sense of place, in authenticity.

It’s all about getting back to the nature of things and being an animal in a pure landscape. That’s always the thing for me. You want to disappear into the “greater.”

Will that be the case when you do Aquaman too?

Yeah, I think so. [Laughs] That’s what pretending is, somehow. It’s willing yourself to enter into that stream. Whether it’s being strapped in body harnesses speaking lines of exposition in Aquaman or improvising in a Florida hotel—or doing some really challenging stuff with Abel [Ferrara] or some really scary stuff with Lars [von Trier], all the films have that same thread. I don’t judge one over another. You can’t go to the same world all the time.

The Florida Project plays the New York Film Festival Oct 1 and 3. It opens Oct 6. Visit the festival's site for tickets.