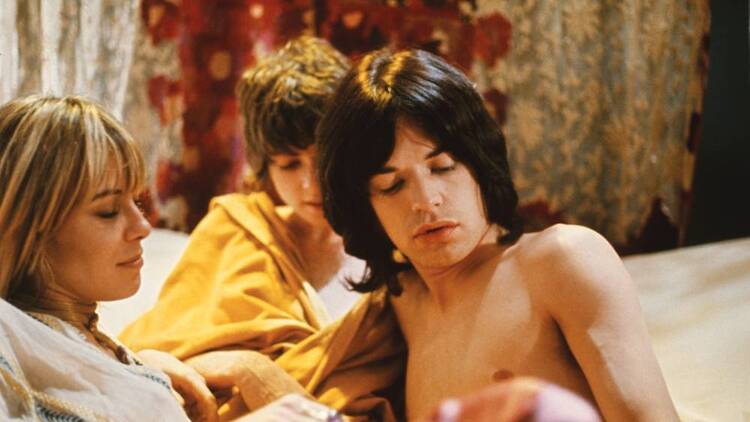

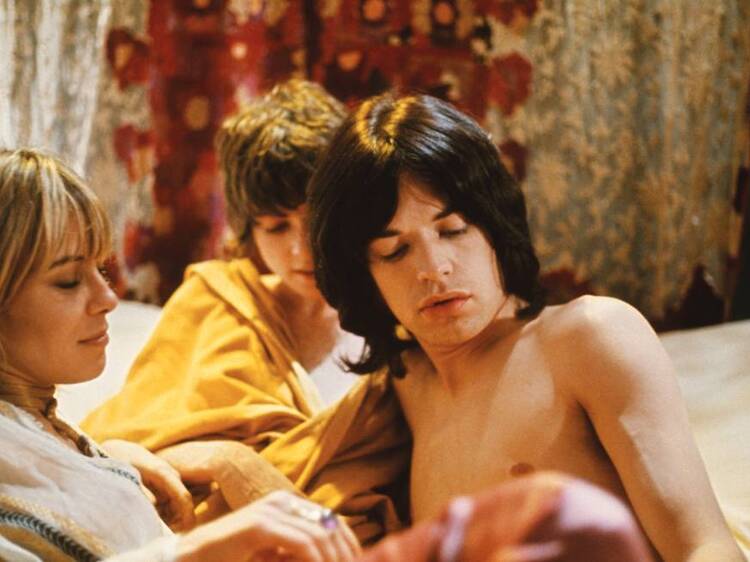

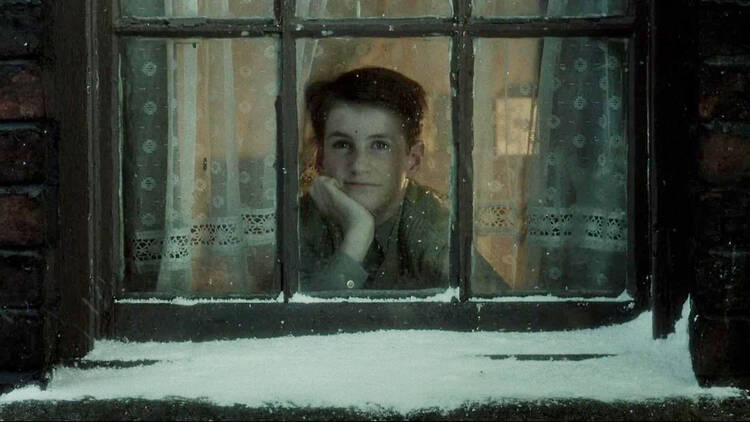

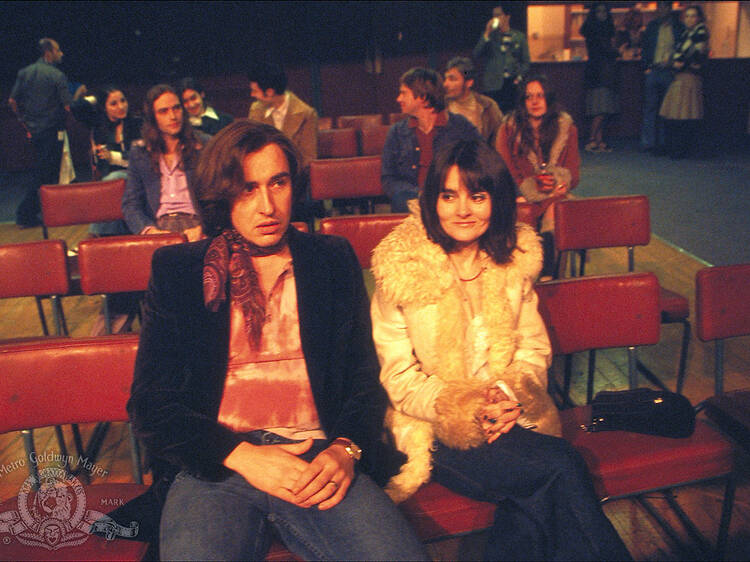

1. Don't Look Now (1973)

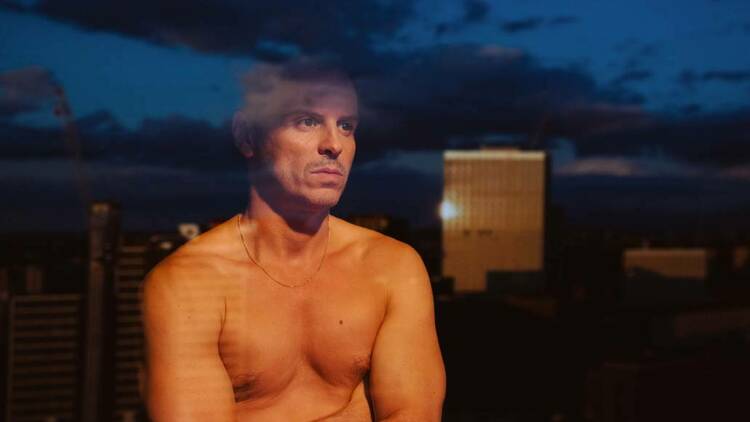

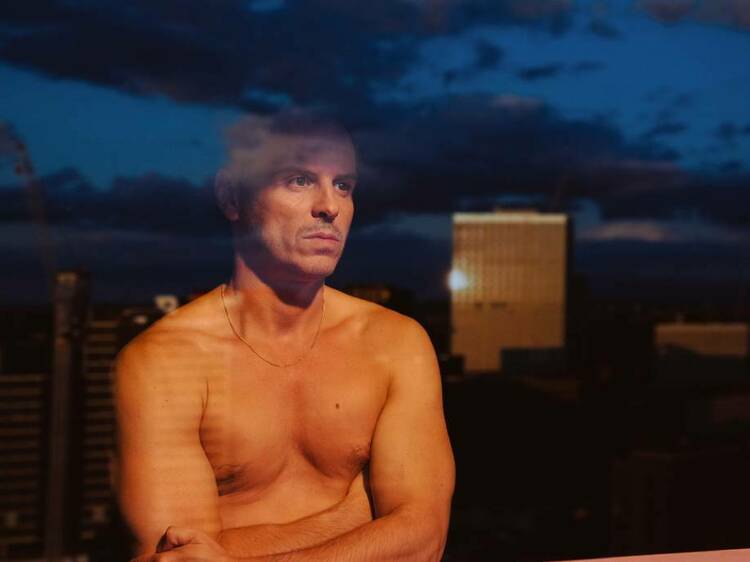

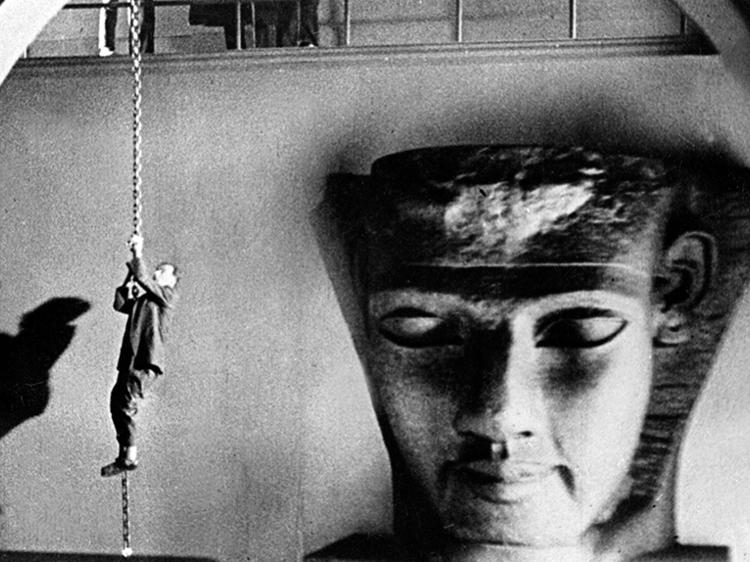

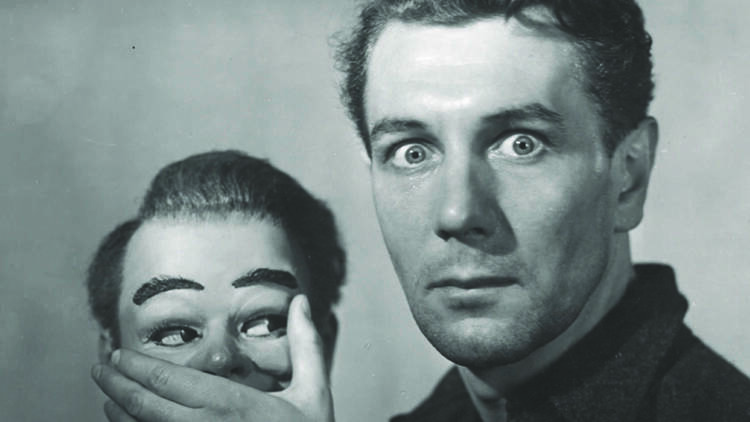

Cast Julie Christie, Donald Sutherland

The number one film on our list of greatest British movies, is Nicolas Roeg’s hallucinatory 1973 Daphne du Maurier adaptation – the story of a couple, played by Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland, who decamp to a spooky Venice after the death by drowning of their daughter. We can speculate on the roots of its popularity: that it satisfies the genre and arthouse crowds; that it uses framing, sound, editing and camera movement to unreel a transfixing tale and flesh out excruciatingly authentic characters; that it dares to coax out the ghosts lurking in every watery passageway in Venice, Europe’s most ornate and singular city; that it contains arguably the greatest sex scene on film. Or, we can just accept it as a movie whose every glorious frame is bursting with meaning, emotion and mystery, and which stands as the crowning achievement of one of Britain’s true iconoclasts and masters of cinema.