Last summer, plans to meet up at the beach with my sisters fell through—but with a nonrefundable airline ticket to Boston and an Amtrak ticket up the coast to Maine, I embarked on the trip anyway. In the charming town of Boothbay Harbor, I decided to spend an afternoon kayaking. After all, at home in northern California, I love going out on Lake Natoma. I’d previously run into a staff member of the Bluebird Ocean Point Inn at the grocery store and despite being off duty, she’d generously and enthusiastically told me how fun it is to kayak in Boothbay Harbor and that I’d get the chance to see a lighthouse and shipwrecks.

As someone used to sit-on-top kayaks, I felt a little anxious when the kind woman at Maine Kayak directed me to insert my legs into the vessel. I suddenly recalled every video I've ever seen of people doing kayak rolls, trapped upside down underwater until they oar their way out. Yikes. She also instructed me on how to use the rudder system; this kayak was a lot more complicated than any I'd ever encountered before; with foot pedals, I’d manipulate to steer the kayak in open water with wind. Speaking of that open water… sharks crossed my mind.

I set out within the safety of the harbor itself, lined with restaurants and brewpubs, and paddled beneath the 1901 wooden footbridge that stretches over the narrow part of the inlet. A quaint bridgetender's house sits right in the middle of it. Soon, though, choppy waves rose. I’d been instructed to face waves head-on to avoid tipping over, although that felt counterintuitive. I had to cross a mildly scary shipping lane with speed boats creating swells and two-story cruising boats blasting loud music.

I found peace once I'd mastered that teeth-grinding experience and was enchanted when a harbor seal bobbed up to check on me. We shared eye contact, and I was filled with a rush of happiness that in all the water around us, the seal had found me, and we were having a moment.

The rudder proved to be wonderful, providing great assistance with maneuverability. I made my way past several small islands, constantly checking the waterproof map on my kayak because things I saw in the real world didn’t exactly square with how they looked on the map. At one point, I pulled up to the island gas station (a platform with pumps for boats) to make sure I was on the right course.

Eventually, I made my way to the ominously named Burnt Island, which is host to a small lighthouse. Disembarking, I pulled the kayak up onto the beach so it wouldn’t float away without me. I wandered the island—for quite a while, the only person on it—signed its waterproof guestbook and ate the picnic lunch I’d got at the grocery store that started this adventure. You can only get to the Burnt Island lighthouse by water. It dates to 1821 (but its light wasn’t electrified until 1961) and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Then I put my kayak back in to head up the other side of the harbor to search for Mill Cove, where the shipwrecks are. Yes, shipwrecks plural! Again, I had trouble reading the map and nearly gave up and had to ask directions from a man hosing down the side of his yacht. I had to backtrack to find the cove’s opening. I had no idea what the shipwrecks would look like but had imagined that I would peer down through the water at them.

To my surprise, they were in shallow enough water that the remains were visible above the water line. In fact, I was wondering to myself, “What are these huge banks?" until a lightbulb went off: their curving nature indicated that they were skeletonized hulls. Seaweed drapes the wood so thoroughly it almost “reads” as earth. You can actually kayak between the walls of a single ship (so that you would be “on board” if the full ship still existed) and imagine what the full schooner looked like before the masts and sails and rigging gave up. There are two wrecks close to each other and a third lies closer to shore (swimmers at Mill Cove could swim to these wrecks without a kayak).

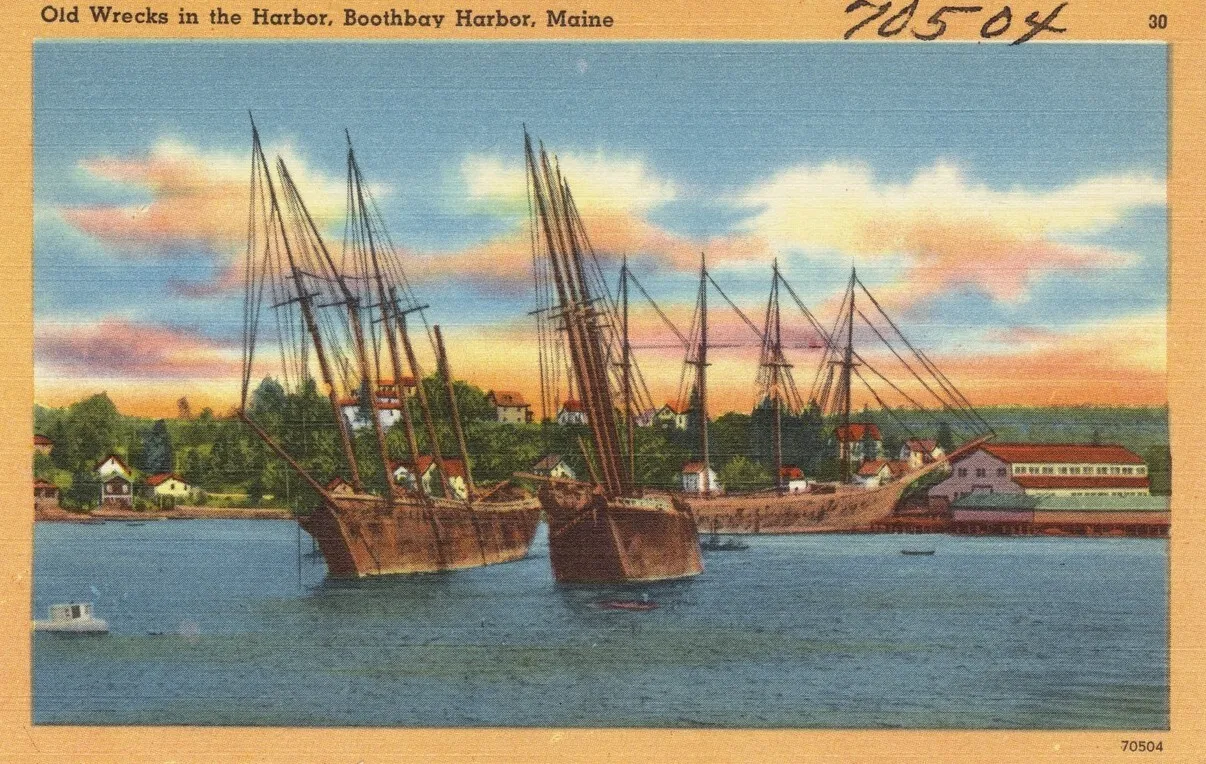

It was a fearsome experience gliding over the wooden hulls of these 1800s vessels, grounded forever and decaying, my paddle making a quiet 'plsssh' sound, I wondered if the ghosts could hear. The postcard below shows the ships before they decayed, and the image below shows my red kayak between two sides of one ship's hull. There is so much breakage and sprawled debris (including plenty to see underwater) that it is hard to tell what you're looking at sometimes; I needed my own Bob Ballard to interpret this archeological site.

For a history buff, this was an incredible moment I’ll never forget. What tales these ships could tell! This Central Maine article reveals that they’re what’s left of a “ghost fleet” of abandoned vessels. One ship’s name is the weirdly specific Edna M. McKnight. This is a 209-foot, four-masted schooner built in 1918 and damaged so badly in a 1926 storm that she was hauled to Boothbay Harbor to rot. According to Wreck Hunter, “Wreckage is now mostly slumped down below the water line.” The ship right next to her is the (also specific— who knew ships had middle names?) Courtney C. Houck, built in 1913 and laid up in the harbor in 1930 and never returned to service. She’s a larger ship at 1,627 tons compared to Edna’s 1,326. In 1945, people celebrating the end of World War II set fire to the two ships, and one burned to the water, according to HazeGray.org, which explains why the remains don’t instantly scream “shipwreck.”

The entire outing took about four hours (it would've been much shorter if I hadn’t gotten lost) and thrilled me with historical fascination and a little bit of pride. I found peace in parts of the harbor where I was the only one around, methodically rowing and feeling placid. Although my trip was supposed to be filled with chattering along with sisters (which would have been awesome), I loved the private experience of awe that washes over you when you are the only one there.

I celebrated my safe return with seafood, sitting dockside to have a glass of Chardonnay and garlic white wine mussels at The Whale’s Tail & Seafarer Pub, as the sun started lowering over the water. The pub’s not far from a giant statue of a yellow raincoated fisherman. Then I walked back across the footbridge again for a lobster roll at the Tugboat Inn, housed in a grounded historic tugboat, The Maine, whose wheelhouse you can stop in and look at. What could be more “Maine” than a lobster roll after a sea kayak paddle?

If you visit Boothbay Harbor, go at low tide to make sure you can see the wrecks.