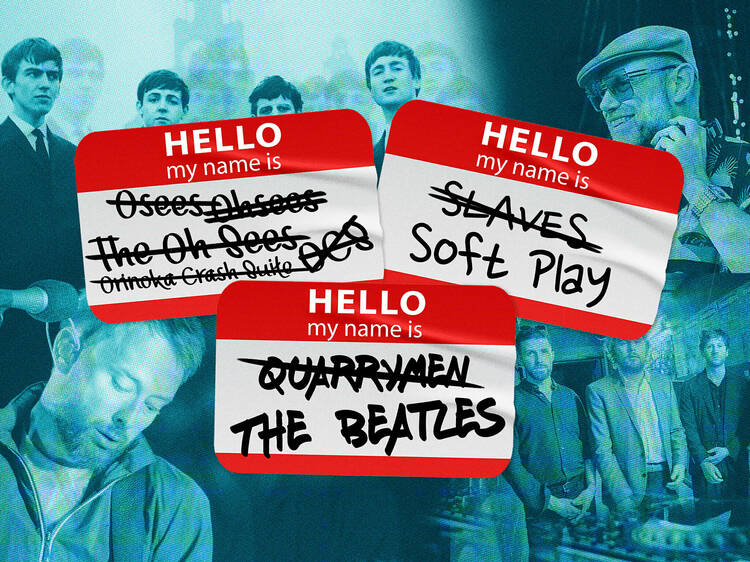

Musicians have been changing their names since, well, since forever. Some of the biggest names in music history have flip-flopped over what they wanted to be called. The Beatles were once the Quarrymen, Joy Division were Warsaw, Radiohead were On a Friday.

Some change names to distinguish between eras or projects (Sonic Youth/Ciccone Youth, MF DOOM/King Geedorah/Viktor Vaughn/Metal Fingers, Yo La Tengo/Condo Fucks) or for legal reasons, like Parliament/Funkadelic, where George Clinton wanted to push past the collapse of a record label and keep releasing new music. In October, English band Easy Life were pressured to play their final show under their current name after the owners of the easyJet brand, easyGroup, filed a high court lawsuit claiming their name infringed on a trademark. (The band decided not to defend the lawsuit due to the financial burden.) Others seem to twist and change just for the fun of it, like John Dwyer, who has changed the name of his beloved underground rockers Osees from Ohsees and The Oh Sees to Thee Oh Sees and OCS.

Recently, it seems like there’s been a whole load more artist name changes than usual. Over the past few years, a bunch of established artists have rebranded without changing anything else like their sound or image. What’s behind this shift? And what do fans think of it all?

Regrets, I’ve had a few...

‘I’d never been crazy about the name, even though it was admittedly distinctive and memorable,’ says Dave Lee, the house DJ formerly known as Joey Negro. ‘When I came up with the alias it was for a single I was releasing on a New York label Nu Groove in 1990 and I only envisioned using it the once. The record was coming over to the UK as an import and I wanted to think of a name that sounded like a Hispanic New Yorker.’

The name stuck. Then, in July 2020, Lee changed his stage name, sensing a sea change and public backlash following the death of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests.

‘When things started heating up online for The Black Madonna with online petitions for her to change her name I got tagged in some of the posts, saying, “How about Joey Negro,” etcetera,’ Lee says. ‘This went on for a few weeks then The Black Madonna changed her name. At that point, a lot of the heat came directly onto me.’

Throughout his entire career up to then, Lee says no one had told him that they’d found his stage name offensive. Still, he says he’d always had reservations about ‘Joey Negro’: even though he’d always thought the name should have a Spanish pronunciation (a first syllable of ‘neh’ rather than ‘knee’), he found it a little cringy in some situations. And so Lee set about finding a new name.

‘I had discussed it with the people around me and everyone had very different opinions,’ he says. ‘The problem with this situation is that there isn’t really anyone you can ask for advice, as it’s an uncharted territory.’

The problem with this situation is that there isn’t really anyone you can ask for advice – it’s an uncharted territory

Lee considered several options (including ‘Joey Nero’) before deciding on his birthname, though he wishes he’d spent more time thinking over name options. He thought Dave Lee wasn’t just the safest option but also thought it wouldn’t impact his brand too much, as a reasonable amount of his fanbase already knew his real name.

But several people around Lee are still split on his name change – and some fans don’t support the change, either. ‘Since I dropped the name I get endless people approaching me at gigs telling me I shouldn’t have done so,’ says Lee. ‘Some are quite annoyed about it.’

Under (social) pressure

Ultimately, many name changes come (are or at least perceived to come) from pressure from fans and society more widely. A study a few years ago found that millennials and Gen-Z are far bigger champions of social issues than previous generations. Issues like racial justice, LGBTQ+ rights and gender equality are important to these groups. And given that these generations are huge consumers of music – and that even younger audiences may be even more conscious – it makes economic sense for artists to bow to social pressure.

There are countless examples of artists changing due to having problematic names, whether they were pressured to or not. The Blessed Madonna stopped performing as The Black Madonna, saying that the name had ‘been a point of controversy, confusion, pain and frustration that distracts from things that are a thousand times more important than any single word in that name.’ Gilla Band ditched their ‘misgendered’ old alias Girl Band, saying it ‘was chosen without much thought, from a place of naivety and ignorance’. Citing a desire to avoid ‘isolationist, antagonistic nationalism’, Sea Power trimmed down the potentially-imperial-nostalgic British Sea Power. Most recently, Scaler switched from Scalping after apparently becoming aware of ‘how offensive [the name] can be to Indigenous cultures’.

Many might, understandably (and like Dave Lee), point to the Black Lives Matter protests of summer 2020 as motivating this shift in attitude to musicians’ names. While the death of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery brought racism and police brutality to the foreground (directly impacting the likes of the Blessed Madonna, who changed her name in July 2020), it also carried many other kinds of social issues and causes into the light. It took some artists longer to change their names (Sea Power and Gilla Band changed tack in August and November 2021, respectively), but it seems clear that there are very similar attitudes motivating them.

Punk’s dead

When Soft Play ditched their old name Slaves – stating that the name ‘doesn’t represent who we are as people’ – they were plonked into the middle of a cultural tug-of-war. Comments under the Instagram post announcing the change saw hundreds of disparaging comments: the duo were branded ‘absolute bottle jobs’, with some saying the move was ‘not very punk rock’.

Of course, it’s easy to be a culture warrior when shielded by the anonymity of a keyboard and cartoon profile pic. And while plenty of fans were no doubt genuinely irritated by Soft Play’s name change, others were more understanding.

‘When I was young and [Slaves] first came out, I didn’t really bat an eyelid,’ says Soft Play fan Emma. ‘When you’re 17, you don’t really think about that stuff. And if there’s no one around you that is willing to talk about history or politics, you don’t really know any better.

Slavery still exists and it’s understandable why some people might’ve been offended by that old name

‘But then you get older and start to think more about the world around you. You learn more about the world and the severity of some words. Slavery still exists and it’s understandable why some people might’ve been offended by that old name,’ she says. When Slaves got big in the mid 2010s, many of the band’s fans tended to be on the younger, late-teenage side. As the band matured, so did their fans; it isn’t hard to see why both might now favour tweaking the brand into something less controversial.

You’ve got a friend in me

The phrase ‘separating the art from the artist’ has long been bandied around by people as some kind of justification for enjoying music made by people they don’t admire on a personal, non-musical level. Yep, it applies to Morrissey – but it doesn’t just apply to Morrissey.

For some people, knowing a musician is progressively-minded can actively make them want to listen to them more. A name change can really benefit that. ‘I admire them more because they weren’t pressured, they weren’t backed into a corner,’ says Matt, a Scaler/Scalping fan from London. He commends the name change on several levels, in part because the band has changed its brand just as it is on the verge of getting bigger. Now they’re more in the public eye and their name has more exposure, Scaler don’t want to risk offending potential new audiences.

And while that might seem like an act of self-restriction, it’s also potentially educative for longer-term followers. Matt previously assumed that the Scalping name was concerned with money (wheeler dealers, price gougers and the like), so having his attention drawn to other meanings – namely the practice of tearing off the scalp of one’s enemy and taking it as a war trophy – is actually helpful.

‘It educates you on the fact that these things can be offensive in different contexts,’ he says. And for him, that’s a reason to continue being a fan. ‘I already like their music. I wouldn’t listen to someone just because they changed how they present themselves,’ he says. ‘But it makes you more appreciative of who they are as people, helping you relate to their sounds.’

Politics as usual

On the other hand, there are people out there who can see through name changes for what they can so often be: superficial acts designed to placate crowds with an easy, quick fix.

The Soft Play switch lays bare how people’s attitude towards (and reaction to) name changes can depend on a whole load of factors – including political affiliation. Opposition to name change is often split along political lines. But it isn’t as easy as lefties being supportive and the right screaming ‘snowflake’.

Gilla Band (fka Girl Band) fan Dan from London has a few thoughts: ‘Generally speaking, right wingers see language as some fixed thing that doesn’t move or change as society changes,’ he says. In other words, they’re more likely to get angry or annoyed when artists change to suit the times. ‘It’s about whether we view languages as dynamic and shifting or concrete and fixed,’ Dan reckons.

It’s about whether we view languages as dynamic and shifting or concrete and fixed

But lefties can be just as critical of name changing – if not more – just for different reasons. After all, if a brand change is just that, leading to no concrete action or difference in how an artist approaches the industry, it’s all empty, all just for show. ‘For me, I would say that Gilla Band changing their name is utterly pointless if they’re not then going to have a structural approach where, for example, they refuse to play festivals that don’t have a 50/50 gender split,’ says Dan.

‘If they go out and do a two-year album tour cycle that has no women playing with them on tour, and if they don’t use their platform as a pretty big band in the alternative scene to demand that there’s decent percentages of women artists playing, then what’s the point?’ Does Dan feel any better or worse of Gilla Band following the name change? ‘The jury’s out on that,’ he says.

Snowflakes, cancel-culture-vultures, woke warriors, war-on-wokers: no name change will satisfy everyone. Recent name changes might be more publically reasoned or socially motivated than in the past, but for the most part, artists will continue to do what they please – unless they’re being attacked by a budget airline, that is.

Easy Life still haven’t announced a new name, although plenty of fans have piped up with suggestions. ‘Difficult Life’, anyone?