Welcome to Digbeth, Birmingham. This post-industrial, post-hipster patchwork of nightclubs and gaming cafés is what Hackney Wick is to London, or Ancoats to Manchester. To the west, former warehouses and custard factories are stuffed with sweaty students bobbing to tech-house, spilling out onto the pavement doing nos balloons and crying over cheesy chips. To the east, it’s a grey wasteland of flattened rubble and cranes, slowly assembling another clinical block of flats, offices and (probably) a PureGym.

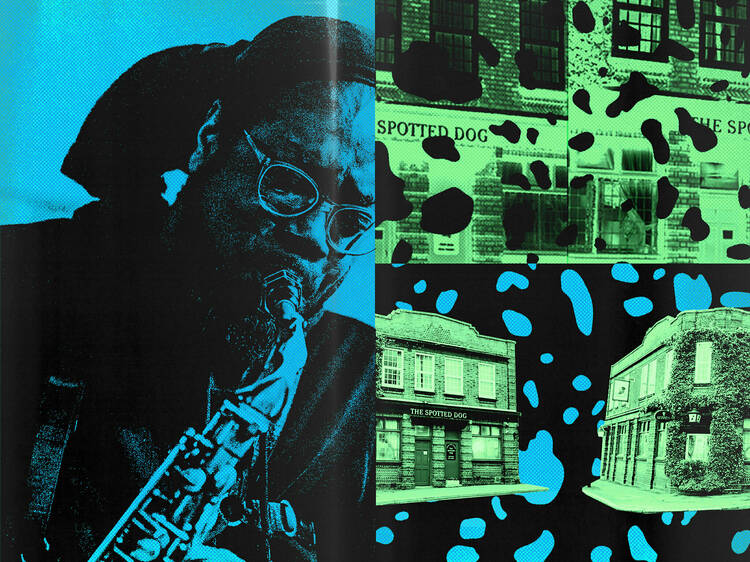

Somewhere in between sits The Spotted Dog: an unassuming red-brick Irish pub on Warwick Street. Rewind 40 years, and there was a boozer on every corner, places workers from nearby factories would sling pints at lunchtime before heading back to the production-line slog. These days, the Dog stands alone, and it just so happens to be the centre of the UK’s youngest, vibiest jazz scene.

The venue has hosted weekly jazz nights every Tuesday for the past 13 years, a routine started by Mike Fletcher and Miriam Pau, former students of Birmingham Conservatoire’s renowned jazz department, to platform local bands and artists. These days, ‘Jazz at The Dog’ is run by saxophonist Liam Brennan, 25, and drummer Kai Chareunsy, 24: the latest to pick up the baton in a line of young musicians committed to the scene, which is now well respected in jazz circles.

Over the years, The Dog has hosted internationally renowned musicians, including saxophonist Stan Sulzmann, pianist and singer Liane Carroll, singer Heidi Vogel and trumpeter Byron Wallen, as well as more contemporary artists like saxophonist (and BBC Young Musician of the Year) Xhosa Cole. ‘It’s cool seeing those types of names in such an intimate space,’ says one punter. Even legendary American trumpeter Wynton Marsalis has shown his face.

As pubs go, The Dog is nice. Portraits of musicians who’ve played there hang on one wall, unclothed mannequins and creepy china dolls dangle from the ceiling, and there’s also an unexpectedly large beer garden, which Brennan and Chareunsy used to host gigs at the tail end of the pandemic. The building dates back to 1700 – there’s been a pub on the site for more than a century – and it’s the type of place where you can basically smell the history amid all the hoppy musk.

‘It’s a weird place to start a gig,’ says Brennan. ‘And it can be quite loud with people ordering drinks at the bar and that type of thing. But it’s very accessible – there’s no pressure on having to buy a ticket, we just ask for a suggested donation of a fiver. And, obviously, it’s worked really well.’

It’s the type of place where you can basically smell the history amid all the hoppy musk

Only recently did the jazz night receive ‘a bit’ of Arts Council funding. Previously, it relied on donations and the goodwill of the venue to keep going. But there’s a reason why relatively big names have been willing to play for less-than-standard rates.

At the back of the venue, they take all of the tables out and line up bar stools in front of the ‘stage’. The rest of the pub functions as normal, creating a real sense of warmth to the whole thing, as though you’d stumbled across a band practice in someone’s living room. ‘But we wouldn’t want anyone to think it’s, like, a background-music gig,’ says Brennan. ‘We try to create a combination between a more formal and social atmosphere.’

The events typically consist of two 45-minute sets from a booked artist before audience members are invited to join in with a jam session which stretches into the early hours. This is when the night properly heats up: music students bounce off old-time locals and squeaky beginners, descending into a sort of Guinness-aided harmonic chaos.

And while the duo are committed to ‘preserving’ straight jazz – at a time when many contemporary jazz musicians are embracing all sorts of crossover genres – the offering is far from boring. ‘A common misconception is because the structure of down-the-line classic jazz seems relatively rigid, it can’t be necessarily modern or creative in itself,’ says Brennan. ‘But once you’re in, it’s pretty open. It’s just like a language.’

Take tonight, for example. Charlotte Keeffe is a trumpeter from London, heading up a quartet of drums, double bass and piano. ‘I was actually quite surprised they invited me,’ she says. ‘I’m quite experimental.’

It’s a Tuesday in March, and two whiskery older men in scratchy-looking Fair Isle jumpers have arrived early, sitting with five pint glasses between them. There are students with moustaches, couples on dates and girls with black-lined eyes looking like they never grew out of their Lana Del Rey era. At the back, there’s a large group of lads in identical long-hair-beanie-hat get-ups, whispering over IPAs.

Keeffe picks up her trumpet and looks expectant before lurching into a long, single note, to which the rest of the band respond in a frantic improv. Faces are pulled and saliva is spat, fingers moving up and down the brass like a hurried spider. The bass player picks up a bow and runs it over the furthest point of the strings, screeching, before Keefe’s trumpet lets out a series of deep farting noises, twisting the sound into something phantom and unnerving. ‘Over time, my instruments have become sound brushes – I’m thinking of shapes in my mind rather than traditional notations,’ she says, stopping for breath before slipping into a spoken-word number.

Unfortunately, The Dog’s landlord – John Tighe, a red-faced man with wirey white hair – isn’t exactly a fan of the music. He’s not into jazz at all, for that matter. ‘Ironically, I can’t stand the genre,’ he says, lighting up a cigarette before the show. ‘“Improv” they call it – I call it “needing improvement”. I was brought up on Chuck Berry and modern swing. This is a bit abstract for me.’

Ironically, I can’t stand the genre. ‘Improv’ they call it – I call it ‘needing improvement’

He softens. ‘But they have done a great job of setting it up,’ he adds. ‘A lot of students come along, and it works. I wouldn’t inflict my bad taste in music on anybody else.’

Still, live music has played a part in the venue ever since Tighe bought the pub 38 years ago with his wife, who he’s lived with upstairs all this time. (These days, Mondays are reserved for traditional Irish music, and Thursdays for blues.) ‘I’ve got all the deeds going back to 1775 on parchment, when this place changed hands as a farm workshop, would you believe,’ he says.

Digbeth is unrecognisable from when he took ownership of The Dog in the 1980s – and not just because of changing industry. Tighe says it’s been a constant battle between independent venues like The Dog, property developers and the council, and he worries that he could be the next to go. ‘From upstairs, I can see 13 tower cranes building apartments,’ he says with a scoff. ‘They’re going to be charging a grand a month for poor people to move into.’

Since April last year, 22 grassroots music venues have closed in the UK, with two fifths of them citing building redevelopment as the main reason. Jazz at The Dog has already had to reduce its hours due to complaints: pre-pandemic, jam sessions previously went on until 3am and were ‘quite boozy’. Still, keeping the nights affordable and open to as many people as possible remains a priority, so the organisers have had no choice but to comply. ‘It’s very hard to keep things going, unless you have the backing of the venue itself,’ says Chareunsy.

In the decade-odd since Jazz at The Dog was set up, it’s spread by word of mouth, with very limited intentional promo, developing a cult-like status which has only been bolstered by the talent coming in from local music students. Now, elsewhere in the city, the jazz scene is popping off. From upstairs at Cherry Reds to Warehouse Café and Neighbourhd, new nights are springing up in other venues, many fusing the genre with hip hop, broken beat and spoken word.

That’s not to mention all of the Brum festivals nodding to jazz. As well as the long-running Mostly Jazz, Funk & Soul Festival and the city-wide Birmingham Jazz & Blues Festival, there’s also Talking Drum Fest: Xhosa Cole’s new, two-day endeavour at The Edge, which looks to celebrate the drum throughout the African diaspora.

It’s almost comical that one of the hubs of such a vibrant scene should be a random pub surrounded by rubble and bleak building work. But then again, it sort of makes sense. Scenes need spaces, consistency and a reliable community. And with the warm ecosystem of musicians and fans who have assembled round The Dog over the past decade, it’s not surprising that it’s lasted so long.