I’m on a tour of the Real Good Chicken Company's headquarters and it’s frying my mind. Welcomed by a chirpy employee into a labyrinthine warehouse, a small group of us are taken to the first room, introducing us to RGC’s fast food plucky mascot Chicky Ricky.

After a quick shift operating the ‘head remover’ machine inside the factory and visiting a museum of vintage RGC promotional merch, we witness Ricky’s tragic demise as he is deemed to be out-of-date by clinical big cheese The Boss. Off we go to a mausoleum to throw sachets of salt on his coffin. Consider Ricky’s bucket kicked and my head clucked.

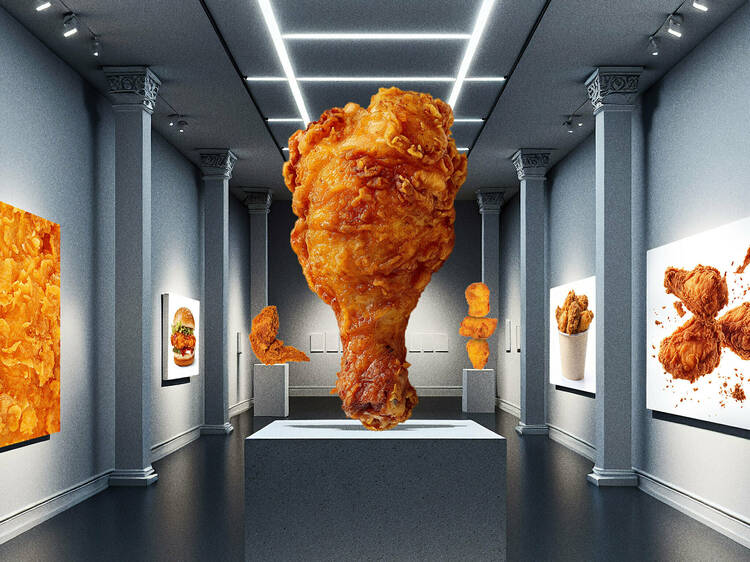

Except none of this, of course, is actually real. I’m in the make-believe fantasy of Sweet Dreams, the new immersive exhibition from Factory International in Manchester taking you behind the scenes of an imagined chicken conglomerate. Voiced by the likes of Munya Chawawa and Morgana Robinson and designed by motion graphics collective Marshmallow Laser Feast, it aims to change the way we think about fast food.

‘We know chicken is adored. We didn't want to be judgy or preachy or moralistic. We just wanted to look at the cartoon mascots who are effectively spoon feeding us. It’s funny and tragic,’ says founder Robin McNicholas, before quoting RGC’s slogan: ‘Delicious Lies Within!’

The pecking order

Sweet Dreams isn’t the only exhibition banging the drumstick for wings; there’s been a glut of showcases recently using the fried crispy stuff as a muse. Artists of the past have represented fried chicken: see David Hammons' iconic sculptures from the 1990s featuring suspended wings. But it’s taken flight recently. The most paltry of poultry has suddenly become pure poetry.

Don’t believe us? Just a few months ago, artist Jack Hirons showcased his solo exhibition Fowl Play at OOF Gallery, the contemporary art space in the grounds of the Spurs stadium. It featured oil paintings of cock fighting, battery farms and US senators eating wings, plus a stained-glass window inspired by chicken shops using actual cadavers, bones and all. ‘About seven years ago I started experimenting with producing a black paint from leftover chicken bones that were turned into charcoal and crushed to form the pigment,’ he explains.

Across the pond, artist and spoof toy creator Dano Brown has just put on his second Nuggets Only Two exhibition in Chicago, inviting nearly 30 artists to cook-up work inspired by golden goujons for the second time. ‘I think people are naturally attracted to the silly and strange and an entire art exhibit with dozens of talented artists making nothing but chicken-nugget-related art checks both of those boxes,’ he says.

Chickenism has already become commercialised. Last year, McDonald's Hong Kong launched its own McNuggets art exhibition, inspired by pop cultural lore including Usain Bolt allegedly eating 100 nuggets before the Beijing Olympics and Rick and Morty reviving the franchise’s lost Szechuan sauce. It saw 20 artists create immersive works inspired by the dippable and dunkable delights and, of course, an AR experience.

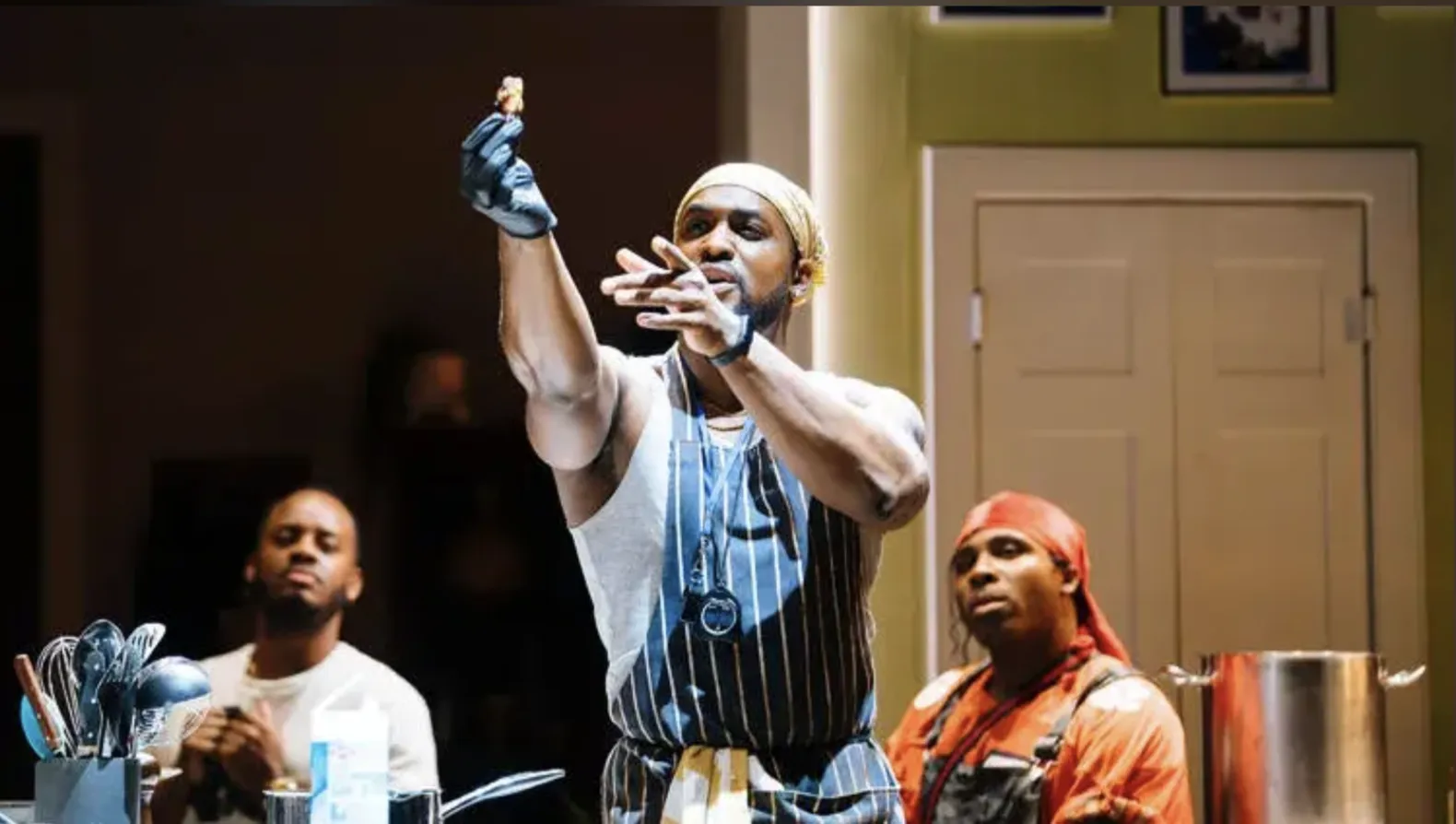

But it’s not just the visual arts playing chicken. There’s drama, too. The Hot Wing King, which is currently showing at the National Theatre, follows a chicken-mad household of Black queer men as they try to create the ultimate hot wing for a competition. Chicken becomes a way to navigate race, masculinity and sexuality in a heartstring-pulling and rib-tickling comedy.

Most bizarre is this year’s South Korean Netflix sleeper hit Chicken Nugget, drawing on the country’s love of fried chicken. It follows a woman who steps into a mysterious machine and suddenly turns into the titular snack. Think Kafka’s Metamorphosis but, err, a nug instead of a bug.

All of this seems to follow in the webbed footsteps of the likes of Chicken Shop Date, Hot Ones and The Chicken Connoisseur. These small-screen shows have taken social media by storm over the last decade, showing that the fast food has mass market appeal when it comes to snackable content. Eating chicken together, after all, makes the perfect backdrop for Amelia Dimoldenberg’s flirty celebrity breadcrumbing or Sean Evan’s candid interviews.

On a wing and a prayer

So, why are we suddenly flocking to fried chicken exhibitions and plays? Firstly, there’s a lot that surrounds the foodstuff that’s aesthetically interesting for artists, like the sugary sweet graphics and ketchup-and-mustard colour palettes. ‘I was living in Bow and started noticing the amount of chicken shops with funny posters in the windows,’ says Siaron Hughes, author of chicken shop compendium Chicken: Low Art, High Calorie, which celebrates the industry’s kitsch design. The book even features an interview with Morris Benjamin Cassonova (Mr Chicken) – the man purportedly behind 90 percent of the UK’s chicken shop designs.

On a similar note, the original idea for Sweet Dreams actually came from McNicholas stumbling across a cannibalistic rooster holding a roast chicken in Tbilisi. ‘It was a weird, hilarious and tragic image that encapsulated a lot,’ he said.

Much of this imagery is also powerfully nostalgic. ‘Some foods really do remind us of the past and trigger nostalgia. I think some might even make people feel like a kid again for a moment,’ Brown says. It makes us feel safe. ‘The cartoonification of our cuisine teleports us back into toddler mode like friendly faces on a box of cereal. It stops us from thinking about the ultra-processed, mechanically reconstituted stuff,’ says McNicholas. ‘Cute eyes shift units,’ he adds.

Plus, if you are what you eat and you make what you know, then it all makes sense. We are collectively munching on bucketloads of the stuff. According to a survey by Slim Chickens (no vested interest to see here), fried chicken has overtaken fish and chips as the UK's national dish. The lowly bird has taken over the high street and the lore of Morleys and the hype of Miami Crispy is still gathering speed.

What’s more, actual fried chicken has become an elevated dish rather than a quick thing to grab when you’re battered. Fowl in St James, for example, only uses soy-free chickens raised on farms practising regenerative agriculture. And at Bébé Bob in Soho you can get a bottle of champers with your Vendée or Landaise chicken.

But the bird has always been a major part of culture, especially for people of colour. As the theatre programme for Hot Wing King notes, the cockerel was represented as being brought down from heaven in ancient Yoruba cosmology and is an integral part of the African diaspora. ‘The chicken wing became a relatively inexpensive and quick way of satisfying hunger and spreading Black joy,’ writes food historian Michael M. Twitty. Similarly, artist Hamja Ahsan has tried to ‘reclaim fried chicken for Muslims’ through his mock halal fried chicken shop designs showing support for Palestine liberation.

Some of this new art is taking this to the next level, granting chicken God-like status. In Sweet Dreams, the backlit chicken shop menu is beatified by turning it into a stained glass window, a trope which also features in Fowl Play. Meanwhile, in Hot Wing King, chicken is compared to the holy communion: ‘The chicken just melted like a wafer of Christ's body and all them bitches just about fell OUTTTTTTT,’ says protagonist Cordell. While the vegans worship seitan, chicken lovers are revering wings.

Chicken, chicken wings

‘Chicken is such a big part of our world, there are nearly four times more chickens on earth than humans,’ says Hiron, of his previous exhibition at OOF. ‘We have totally engineered the bird and in turn it’s been shaping us, both physically and culturally.’

McNicholas agrees: ‘Art and culture is reflecting our obsession with fried chicken. There's a collective reflection on the desires that are playing in the back of our minds and the disconnect we have to the natural world.’

We’ve certainly collectively come a long way since the Nando’s Skank. But have we swapped the tender loving care of a box of cheap and cheerful chicken for something too fancy? There’s a risk that fried chicken goes the same way as hyped-up Guinness or glorified caff grub – working class culture contorted into an extortionate affair. Something that once cost chickenfeed, fetishised for insatiable social media feeds. Or maybe it doesn’t have to be as deep as that.

Either way, all of this fried chicken creativity is tapping into something more than ever before. Whether it’s digging into the history of a diaspora, dissecting animal cruelty or challenging commercialism, there’s food for thought beyond the fun and fakery behind the facade. ‘It's sparked lots of diverse conservations,’ McNicholas says about Sweet Dreams. There’s no single takeaway for visitors. ‘Some people have said it made them hungry and others have addressed their position on eating meat,’ he explains.

So how do I feel as I leave the Real Good Chicken warehouse and walk back through Manchester, passing scores of actually real good chicken shops along the way? Pretty smug actually: I should probably at this point that I’m actually vegan.