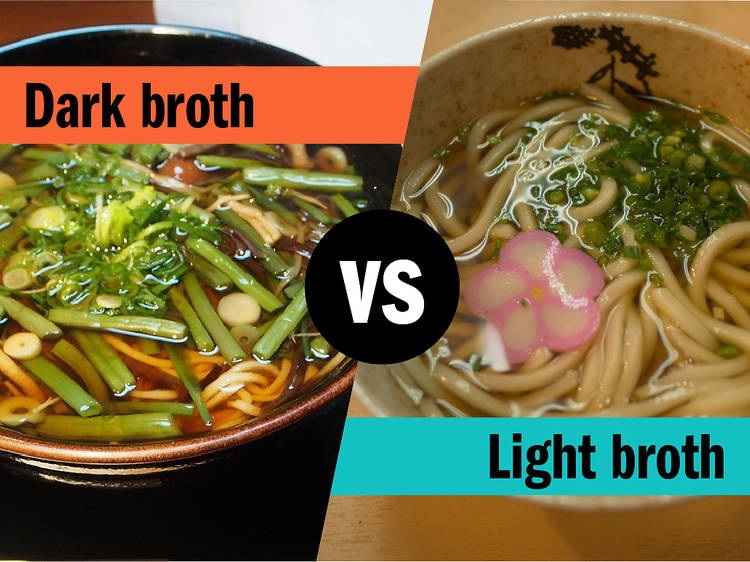

Dark vs. light broth for noodles

Eating noodles in Kanto, you will most likely be slurping up a strong, blackish broth. It’s a combination of katsuo-dashi (stock made with bonito fish flakes) and koikuchi (dark soy sauce).

In Kansai however, the stock is lighter, clear and golden, made with kombu-dashi (stock based on seaweed) and utsukuchi (light soy sauce). It’s said that this difference might have started because the darker broth goes better with soba noodles, which are popular in Kanto, while light broth works better with the udon common in Kansai.