World-class technological spectacles

In an age in which anyone can watch top-level performances from all over the world in high-quality video form at any time, artists need to be prepared to have their work evaluated according to global standards. How to go about doing this while offering international audiences something essentially ‘Japanese’ was the theme of this first talk.

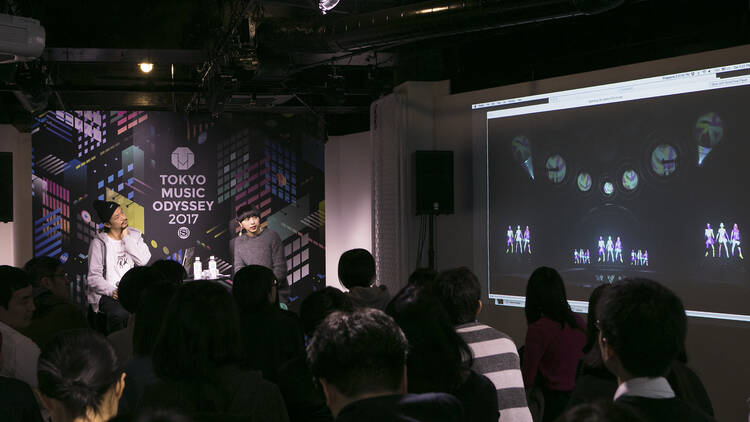

Both media artist Daito Manabe and choreographer Mikiko have won plaudits in Japan and beyond for their innovative work, which fuses technology with physical movement. Their discussion started with a look at the closing ceremony of the Rio Olympics, as both Manabe and Mikiko had a hand in Japan’s show that took place as part of the flag handover ceremony that ended the 2016 Games. Looking ahead at Tokyo 2020, their contributions incorporated technology used in previous works while adding new themes as well.

’Something very Japanese that doesn’t draw on the traditional arts, something that truly represents Tokyo and can be displayed in an attractive way – these are the aspects I had in mind when planning the performance. My form of expression was pointed, but the show managed to win the approval of a diverse audience, from young people to the elderly. As audiences are becoming more demanding, I really tried to show off something challenging, something devoid of compromise.’ (Mikiko)

‘Our show at the ceremony was allocated an eight-minute slot, so every second counts. Simulating the situation and finding out where the limits are was tough. Unbelievably, we couldn’t rehearse at the stadium at all. The dancers would only perform during the actual ceremony, and things like that – we really got a taste of the limitations associated with the Olympics. In Rio, we had issues with the language barrier and the shipping of materials, but similar problems won’t arise here in Japan, so we should be able to engage in creation without having to worry about too many limitations.’ (Daito Manabe)

What, then, can be done to make Tokyo a more creative city? ‘There aren’t enough spaces for experimentation and development. In cities like Paris, there are publicly run studios for artists, so I think also opening places like that in Tokyo would help change things for the better. There are more opportunities for artists abroad than in Japan, so it’s important to increase the amount of spaces that can function as “bases” for activities and other things unique to Japan.’ (Mikiko)

‘Overseas, especially in New York, the crowds at various events are very diverse, so you get a lot of synergy. But in Tokyo, the fashion, geek, music and other communities are very distinct, with minimal overlap. It would be great if we had more places where people from all walks of life could get together.’ (Manabe)

‘Japanese media artists are increasingly moving abroad, as more funding is available there. But if Tokyo can become a true hub for Japan-born content, then both domestic and international artists will surely gather in the city. For example, simply having the name “Broadway” associated with a musical makes people pay attention. Having a Tokyo neighbourhood or area with a similar kind of impact would be great.’ (Manabe)

To wrap things up, Manabe was asked to give practical suggestions as to how the city could be improved. ‘For example, it would be interesting to have a special zone in Japan, with sensors and cameras on every corner, where gathering all kinds of data from people on the street would be allowed.’ This rather out-there suggestion from the ‘technologist’ made the audience laugh, but perhaps he has a point: maybe what Tokyo really needs now is outside-the-box policies that can shake up the status quo.