By Ayako Takahashi

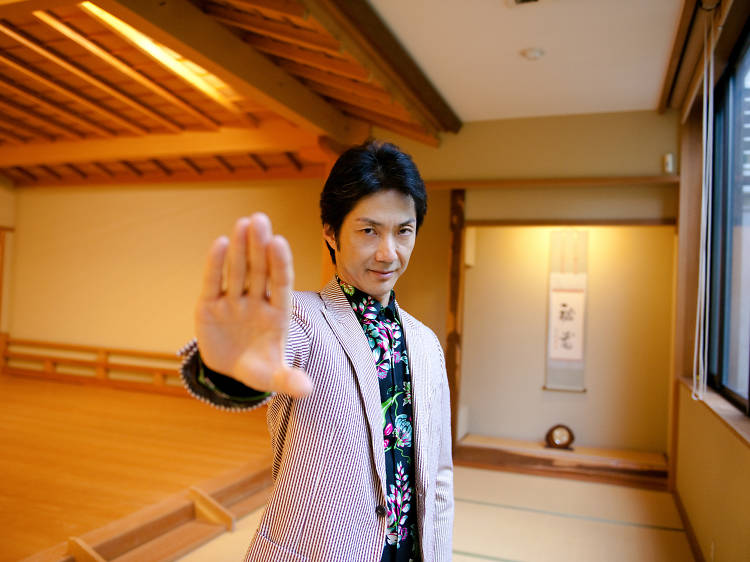

Once he was a clever Yin Yang Master, skilled in fortune-telling and divination (in the film Onmyoji). Another time, he was a beloved blockhead, despite displaying no wisdom, virtue or courage (The Floating Castle). Mansai Nomura shows talent in a variety of acting styles, but at his core is kyogen. Established in the 14th century and recognised by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage, kyogen is a traditional form of Japanese comic theatre and the oldest continually practised form of theatre in existence. Mansai studied under his grandfather, the late Manzo Nomura VI, and his father, Mansaku Nomura. Debuting at the age of three, he is an actor who shoulders the history of kyogen.

The style: yesterday and today

Today’s kyogen is not a perfect replica of what existed long ago, but the theatre does seek to retain certain characteristics. ‘As with the words “thou” and “thy” from Shakespeare’s time, there are words in kyogen that we don’t use nowadays, along with linguistic devices such as rhyming,’ says Mansai. ‘As with Shakespeare’s iambic pentameter, kyogen has a unique elocation technique that requires a classic style. We are particular about maintaining the formal beauty of the interesting sounds and flow of original Japanese.’

Realising that these traditions may make kyogen less accessible to modern audiences, Mansai and his fellow actors are concerned with how to appeal to foreigners and young people unfamiliar with ancient Japanese. Mansai makes every effort to aid the proliferation and penetration of kyogen by introducing it to younger audiences. He has appeared on the children’s TV show, ‘Nihongo de Asobo’ (‘Let’s Play in Japanese’), where he demonstrated the appeal of kyogen. And at the Setagaya Public Theatre, where he holds the title of artistic director, he promoted a Modern Noh Collection series that aimed to fuse classical noh with modern theatre. ‘[The high arts] must not be too inaccessible, but we must also not pander. We need to preserve a sense of tension with the audience,’ he explains. ‘Classics should not be modernised purely to be easily understood; we must treasure their aesthetic standards, while understanding that they are ancient arts that still connect to the present.’

The structure: simple and comedic

The famous kyogen opening line goes like this: Kono atari no mono degozaru. ‘In English, this is often translated as “I am the resident of this house”, but “kono atari” has a broader meaning, so recently I have been using “I am the local...” instead,’ says Mansai. Words aside, though, ‘the character who appears on stage [in this opening scene] is human, like everyone, and symbolises you, the audience. In this way, it is structured like a simple mirror.’

Herein lies one reason for kyogen’s survival over the years – the fact that it’s not complicated in structure. ‘It is spoken, so it is mostly understandable – even for foreigners. If you read about the play in advance, you can grasp the meaning while watching based on context.’ It also has strong comedic elements. ‘Laughter connects people, something that’s keenly felt during our overseas performances,’ says Mansai. That said, Mansai was taught by his father that, while kyogen is comedy, it should be – in this order – ‘beautiful, interesting, and comical’.

The actors: youth vs experience

With its 600-year history, kyogen’s conventions run deep. ‘That the theatre is open not just to young actors but to veterans as well is a very Japanese aspect of kyogen. For a young person, formalities may be formalities and nothing more. However, with older actors, we may feel a significant “spirit” in the slowness of their movements. In that way, they reflect the value of their life experience. To put it in poetic terms, it’s wonderful to see the cherry blossoms in full bloom, but there is also deep meaning in going to a zen temple and seeing a withered old tree with just one or two blossoms.’

What's next for Mansai's kyogen?

This autumn Mansai serves as general advisor to the Tokyo Art Meeting 5 held as part of the Tokyo Culture Creation Project and is performing the kyogen play ‘Sambaso’ along with the 1928 ballet ‘Boléro’ in collaboration with media artist Shiro Takatani. ‘It is a clash between the inspired high art (“Sambaso”) and contemporary art,’ he says. ‘Since this is the most sacred piece of kyogen, we will perform it as is, and fight against, merge with, or fall apart from Takatani’s art.' Mansai decided to add a performance of Maurice Ravel's ‘Boléro’ after his father pointed out the similarity in structure between the ballet and ‘Sambaso’.‘They are similar in that they have many repetitions and they crescendo in an upward spiral. I think the aspects of requiem and prayer to the earth in both of these works are very important in today’s world.’