The burlesque subculture has transformed into a progressive political statement, as well as a welcoming community in Sydney. We spoke to Sydney's queen of burlesque (and Sky Sirens teacher) Porcelain Alice and performer Lottie Lamont (now an instructor at Sky Sirens too) about the local scene.

Sandwiched between a rotisserie chicken shop and a fluorescently-lit Indian grocery store on a busy Surry Hills strip is a velvet-draped window, home to one of Sydney’s most sumptuously dressed mannequins. Think feather-trimmed gossamer robes with bouffant sleeves, oil-slick patent black leather harnesses, bralettes of skin-thin lace and straps like iridescent dragonfly wings. A ceramic leopard gazes up at the mannequin in mid-roar. It looks like an expensive lingerie boutique, or perhaps somewhere a support group for dowagers who’ve just lost their wealthy third husbands meets to plan how they'll spend their inheritances. In the evenings, a few minutes after the hour, a gaggle – made up of mostly women and non-binary people – filters out of a red door in a jumble of activewear, leotards over tights and coats with fishnets peeking out underneath.

That’s because the mannequin’s lingerie, as beautiful as it is, is not the main game at Sky Sirens Academy of Pole, Burlesque and Aerial Artistry. Katia Schwartz, the studio’s owner and founder, manages a team of teachers, made up of sex workers and allies, who run classes on a variety of sensual dance forms. Schwartz is careful to make it clear that within her brocade-wallpapered walls, these moves are taught in ways that respect and illuminate their history.

“This business is definitely sex work created,” says Schwartz, who started out as a stripper, and opened the studio in her mid-twenties. “It’s very important to acknowledge the roots of the business… Here, it’s about the sensual side of pole and really respecting the roots of where pole dancing has come from. It’s not something that should be sanitized or something that needs to be sanitized… What about sex work is dirty?”

In recent years, a kind of pole known as 'pole fitness' – which divorces the practice of pole dancing from its erotic dance roots and focuses instead on the activity as a way to build core and upper body strength – has enjoyed an uptick in popularity. But Schwartz isn’t interested in teaching a form of the practice that removes its associations from the marginalised group which pioneered it. Or performing it.

“When people introduce me, they’ll sometimes say I’m a performer, or an artist, or a burlesque star – and I'm like, I'm not a burlesque star. I'm an erotic dancer. I'm a stripper.”

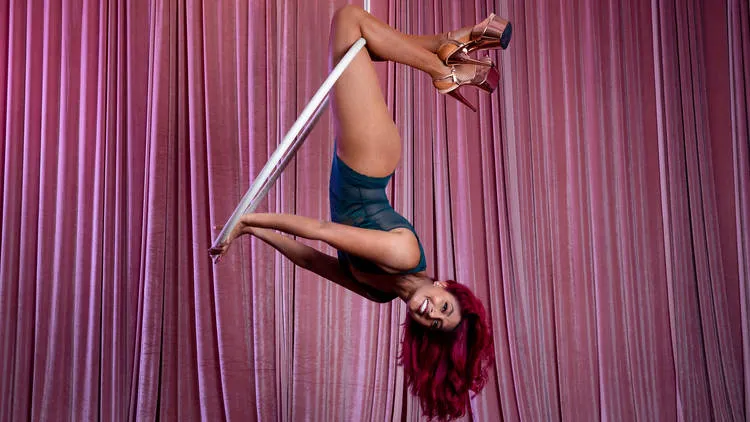

Katia Schwartz. Photograph: Dan Boud

Inside, Sky Sirens is an extroversion of Schwartz’s personal taste for boudoir-chic. The Flamingo Room is canopied by white fabric slings from which dancers twirl, and wallpapered with tessellated pink birds; the Babydoll Room is filled with suspended lyra hoops made for weaving in and out of; the Leopard Luxe Pole Room is fitted with shining golden poles made for back-arching poses. While each space is resplendent, the equipment looks frankly treacherous. But a key focus of the work of Sky Sirens is accessibility: for beginners, for older people, and for those with different physical and intellectual needs.

Schwartz is profoundly Deaf and struggled to find models of success in her world when her hearing starting deteriorating, which is partly why she opened Sky Sirens. By doing so, not only was she able to find her place in the industry, but she has also been able to open doors for others with different access requirements. Two years ago, Sky Sirens hired an accessibility and inclusion coordinator – a role created for Maya Hart, and one Schwartz considers the “most valuable role in the business.”

Hart knows what it's like to enter Sky Sirens as someone who didn’t believe such spaces were created for them.

“When I came here, I was very physically disabled,” they say. “I had a walking frame, and I had undiagnosed autism.

“I saw an Instagram post from one of my friends, of them doing lyra. And I thought: that is the most beautiful place I've ever seen in my life. I want to go, but I don't think they will take me in.

“I'd had issues in the past feeling like my body didn't belong anywhere. I'd always been like a weird outsider. And I was totally blown away by how accepting everyone [at Sky Sirens] was.”

Maya Hart. Photograph: Dan Boud

Under Hart’s direction, Sky Sirens has taken important steps to open up its classes to people with varied needs. Timetables are coded such that low vision people using screen readers can access it; teachers are given training to teach people with disabilities, different physical needs and body types; and sounds and sensations are catalogued and described, so that people with sensory processing disorders can better acclimatise to the class environment.

“Here, these differences are celebrated,” says Hart. “I don't have to water myself down to be a particular way, you know? I am the way that I am. And the students are the way that they are. And that's a wonderful thing.”

Financial accessibility is another aspect of the Sirens’ work, and one that Hart has been instrumental in propelling forward. Sky Sirens offers scholarships, one reserved for aspiring First Nations Sirens, and one for those with financial needs. Each scholarship entitles students to a full discount for a semester of classes, and progressive discounts thereafter.

“It's very easy for a company to say, ‘Hey, we're really accessible. We love people like you!’, says Schwartz. “But then actually not do it with actions.”

While Sky Sirens prides itself on rooting its classes in the history of sex work, on a socio-cultural level, there can be different stakes involved when some women choose to be associated with the industry. For women of colour, the cultural perception of sex work within their communities can double the stigma – something that Sky Sirens teacher and Indian-Australian woman Rachael Jacobs, known in her work as Bolly Golightly, knows all too well.

When she first took a class at Sky Sirens, entranced like Hart by the dazzling colours and studded velvet rooms of the studio, Jacobs noticed that as radical a space as it was, it still saw the world – and dance – through a familiar, colonial perspective.

Rachael Jacobs. Photograph: Dan Boud

That’s how Jacobs, a lifelong dancer and experienced teacher of Indian dance, came to teach Bolly Lyra. In her classes, the aerial style of lyra – in which dancers twirl and move within a hoop suspended from the ceiling – is threaded through with elements of Bollywood dance. This might include the use of a draped shawl; choreography which uses delicate hand movements that imitate lotuses; or traditional footwork that harks back to more traditional styles of Indian dance like Bharatanatyam. She teaches beginners often, climbing on a ladder to lower hoops down for her students. A metres-high hoop is suddenly eye-level. It's suddenly attainable.

“In traditional Indian dancing, we don't have pointed toes and our lines are different – it looks strange to people who think that pointed toes automatically equals ‘beautiful’.”

Most of her students, however, have been exposed only to the Western traditions of dance, and are white themselves – and Jacobs’ experience is not so much with people who want to mock her culture, but are cautious about participating in case it's considered cultural appropriation. It’s something Jacobs is careful to unpack and explain in her classes.

“I teach my classes with a sense of history and tradition and respect for Indian dance. You’re dancing, but you’re also learning about my culture.”

As much as Jacobs’ work lends a refreshing, non-Western perspective into the world of Sky Sirens, it also aims to function in the opposite way: to disrupt norms within her own South Asian community and that of the “good Indian girl."

Those familiar with Indian cinema will recognise the trope, common throughout classics as well as Bollywood films. Her guiding force seems to be recalcitrance, and whatever meagre power she has comes from denying her sexuality, or refusing to expose it: her coyness is expressed in downturned glances, her face half-hidden behind a shawl, her disjointed body revealed only through a man’s gaze. An arch of a foot here, a shawl slipping off her shoulder there. But Jacobs isn’t interested in that kind of representation.

“I don't want to be somebody who's ripping off parts of my culture and exploiting it,” she says. “I want to be respectful. But I also want the world to know that we're fucking powerful. And we can do strong, amazing things. I want that to be seen.”

Whether it's allowing a space for women of colour to explore their sensuality, or opening up a comfortable arena for people with disabilities to move their bodies, or literally lowering the hoop so newcomers can twirl like they've been at it for decades – there's a sense that everything at Sky Sirens aims at eye-level.

Check out the studio (and book in for classes) here.