Content warning: This review and this production includes references to family violence and possible sexual abuse.

It’s all fun and games until the perverted child possession starts.

Wicked fun and silly games. Then not so silly at all. It behoves me well to mention, though, that this brilliant adaptation of Henry James’ 1898 gothic, dread-ratcheting novella is far more subtle in its suggestion of (coughs lightly) inter-sibling debauchery via depraved ghosts. In fact, the whole story hangs in the crucial and unresolved question of what kind of tale it actually is.

Is it a ghost story, where two innocent and impressionable orphans – exposed to a lechery so vile, so diabolical, i.e. hearing a stud valet and bored governess pumping it in the next room – are not just guilelessly modelling this behaviour during playtime, but are actually having their souls invaded by a carnal evil so potent it has risen from the grave?

Or! – and just hear me out on this one – maybe the prudish and pearl-clutching adults in the room are projecting their own paranoias and lived traumas onto two misbehaving little shits? Is this actually a tale of extreme delusion, reality slippage and terrible consequence?

[Hilliar] knows just how and when to turn the screw, tilt the tension, shift the mood, and lay little insinuations throughout.

People of the Victorian era (renowned novelist Henry James being one) were obsessed with the idea of innocence and purity, and were very neurotic about preserving it, especially in young women and children. (Children were in fact a relatively new invented category of life development – kids were once thought to be just ‘small adults’). In fact, the only guaranteed way to protect innocence was through death – you can’t sin when you’re dead.

The new governess who arrives at the country manor of two rich little orphans (after the previous Miss Jessel dropped dead) is a parson’s daughter, whose own inner child tragically died young.

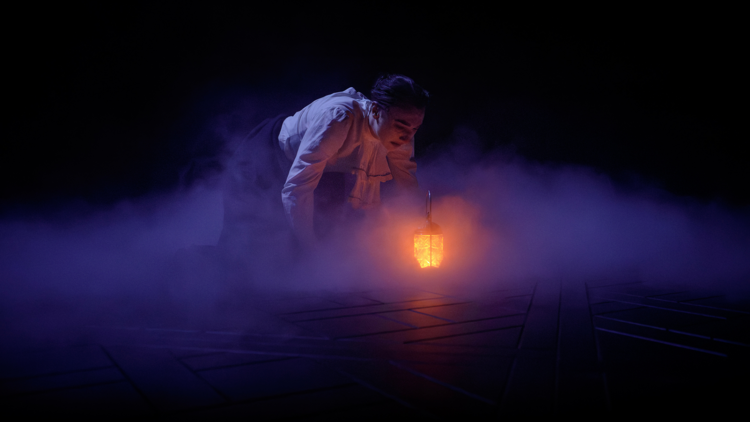

So craftily orchestrated is Richard Hilliar’s modern iteration of The Turn of the Screw, however, that you can’t land too hard on one interpretative side or the other. After all, like the governess, the audience also sees (and perhaps, like me, stiflingly shrieks at) the ghost of the valet Quint, who “carved his face” into the ground and perished in a nasty horse accident. Hamish Elliot’s sumptuously eldritch, deep mahogany set certainly cultivates the idea of a creeping preternatural rot – the dim edges of the manor house gnarled and curling inward, as though some spooky fungus has taken hold. A very cool manor in miniature – an inner lit gothic doll’s house – sits to the side and gives us some idea of the family’s wealth.

No less effective in girding our gullibility is Ryan McDonald’s lighting – a gorgeous yellowy dim glow, like butter that’s on the brink of going rancid. His design makes creative and mood-setting use of candles and shadows and fearsome silhouettes, too, as well as the very occasional jump-scare flash. Chrysoulla Markoulli’s sound – of deep drums and bone-clacking percussives cut through with chilling gasps – is impressive and atmospheric.

This devilishly pensive and thrillingly entertaining revamp is directed by Hilliar too, and presented by his independent company Tooth and Sinew in collaboration with the Seymour Centre. I had my socks blown to smithereens with Hilliar’s UBU, which squelched its putrescent satirical puppet glory back in 2022, and the man brings all his wit, humour, cunning and sensitivity to bear in his latest. He knows just how and when to turn the screw, tilt the tension, shift the mood, and lay little insinuations throughout. It’s the most intellectually invigorating kind of gaslighting. The dialogue is crisp and clever, and a whole lot more fun than Henry James’ staid prose – I was kind of bored when I read the book a few years ago; it didn’t have lines like “Get away from me you whore!”

Aiding Hilliar’s vision is the prodigiously talented ensemble, perfectly cast and flawlessly frocked by Angela Dohert. Of towering stature but teetering authority, in ruffled blouse and plunging black skirt, Lucy Lock has our sympathies as the new governess. What is staged before us is what is in her mind – we see what she sees, but we don’t necessarily believe what she believes.

Pigtailed and petticoated, Kim Clifton makes a very convincing young girl as Flora, a brattish and headstrong little show-off, who thrills in being ‘wicked’ and boils over at the drop of a hat into terrific and calculated tantrums. Martelle Hammer steals some of the scenes in the first half as the superstitious whisky-slipping housekeeper, Mrs Grose, and has just nailed her character’s broad Essex accent. Harry Reid appears briefly but engagingly at the beginning as the child’s philandering uncle and negligent ward, and thereafter as a risen corpse.

It’s Jack Richardson’s Miles, however, who is arguably the most horrible and moving construction, and which – like the play – the audience can never really get to the bottom of. Miles arrives later in Act One, returning home from boarding school. Around ten years old (the character, not the actor), he’s a budding chauvinist and likely a destined predator, a horror of a child with slicked-back blonde hair and a snarling little pink mouth, out of which bursts perfectly elocuted charms and abuse. But, he’s also pitiable. We never know what, if anything, this boy has endured as the young companion to Quint. Richardson incarnates this monster-in-the-making, this “polluted thing” of a perverse world, with frightening, unforgettable ease.

The Turn of the Screw has been adapted into an opera (“Do you feel the turn of the screw? Pushing harder, breaking through!”), a critically acclaimed Netflix series (The Haunting of Bly Manor), and a film that rated just 11 per cent on Rotten Tomatoes (The Turning). In the hands of indie theatre company Tooth and Sinew, this literary classic finds a unique and unnerving edge.

“Ours is a theatre of ideas, of brutality, of humour and of surprise,” the company writes in its website mission statement. “We hope that when you leave, you leave a little confronted, but definitely thinking.” In this twisted twist on an old psychological thriller, they succeed. I can’t wait for what’s next.

The Turn of the Screw plays at the Seymour Centre, Chippendale, until August 12. Tickets range from $33-$49 and you can scoop yours up over here.