In 2010, divisive Serbian artist, Marina Abramovic sat on a plain, light-coloured wooden chair in front of a plain square wooden table for almost eight hours every day for 75 days without food or water. In an identical chair opposite her, patrons of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York could take turns to sit and engage eyes with the artist. It was an extraordinary show of human endurance and a contentious example of performance art.

Those who participated in The Artist Is Present, as it was called, experienced a range of responses – some broke down in tears, some laughed, some could only last a few minutes while others endured for hours.

Australian author, Heather Rose, was one of the patrons bold, brave, or bewitched enough to sit opposite Abramovic several times, and it inspired her to write her award winning novel, The Museum of Modern Love. Through her narrator’s eyes we are privy to the thoughts and feelings of a collection of composite characters Rose created based on the people she observed in the gallery.

Rose’s book is descriptive, hypnotic, exquisitely simple in style, meticulous in recollection. It is contemplative and observational.

Translating something so internalised, intellectually intimate, to the stage is tricky and risky. There’s little doubt that playwright Tom Holloway has the calibre and proven track record to meet the challenge, but his stage adaptation of The Museum of Modern Love, staged as part of Sydney Festival, may well be as polarising as Abramovic’s original work.

One thing that isn’t in dispute is the quality of the actors and the performances. Julian Garner plays pivotal character, Arky, a movie composer struggling to complete a commission while fending off confused emotions about his wife’s terminal illness. Arky is something of an anti-hero; self-absorbed, a little self-pitying, perhaps emotionally immature. There is something irritatingly familiar about this character, the trope of a suffering artist and imperfect man who is trying but failing to deal with big life issues. Garner himself gives a thoughtful performance and will likely endear many audience members to his character.

Arky’s wife, Lydia, is played by Tara Morice, who merely needs to appear on stage to raise the level of any show. Morice has such gravity and presence, such classic features that you could easily sit opposite her in a chair and stare for hours. As Lydia, Morice is austere, almost gothic, but alas, her character development is constrained by the material.

Harriet Gordon-Anderson gives an enthusiastic, intense performance as Alice, the daughter of Arky and Lydia. Alice is perplexed by her father’s response to Lydia’s impending death, while she herself tries to come to terms with it. Jennifer Rani is a delight as Healayas, bringing a bit of zest and brassiness to the ensemble. Healayas is probably the most independent, self-assured character among a group of searching souls. Jane, played by Sophie Gregg, is a school teacher from a southern state, who is desperately seeking meaning and connection, and trespassing across social constructs in the process.

Aileen Huynh, immediately conspicuous thanks to her hot pink hair, is the intently focused PhD student, Brittika, studying Abramovic while, ironically, trying not to be noticed herself. She, in fact, gives a speech about her conflicted relationship with her own physical identity.

Glenn Hazeldine is the rather uncouth critic, Arnold (as well as some minor characters), inappropriately vocal and hopelessly tone deaf to the sentiments of others. Justin Amankwah plays several secondary characters including a cynical co-attendee and a dismissive waiter.

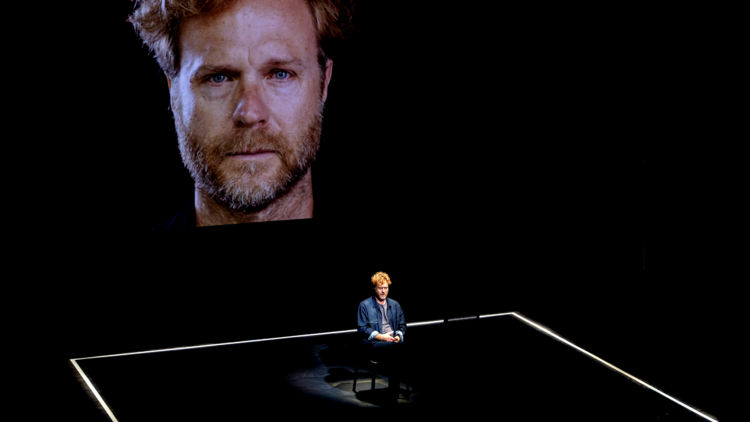

It’s a one-act play with a static set and minimal props, mimicking the stark environment of a gallery. Most of the action takes place in the museum, around Abramovic who is inferred as being somewhere just off stage. Close-up videos of various people’s faces – including but not exclusively the actors – are projected onto a large screen at the rear of the stage, representing the people sitting in the chair opposite Abramovic.

The lighting is dimmed, and there is a claustrophobic feel to the play. It doesn’t really feel intimate though, perhaps because there is a coldness to the design and no real opportunity to develop an attachment to any of the characters. It is that last point – the inability to warm to the characters, or at least, really know them, that may be the fruit-fly in the wine for some attendees. Others, though, will enjoy the sometimes witty, often poetic dialogue. Almost everyone will appreciate the talent on stage.

The Museum of Modern Love plays at the Seymour Centre until January 30. Get your tickets here.