The story of Salome – the princess who demands the head of prophet John the Baptist on a silver platter in return for performing a dance – is a biblical one, referred to in the books of Mark and Matthew. But this young woman, who may have altered the course of history through the power of her dance, is never named in the text.

It really wasn’t until Oscar Wilde’s controversial 1891 play, Salome, that her story became widely known and studied. The play, which forms the basis for Richard Strauss’s 1905 opera, places Salome at the centre of the action as she comes under the lustful gaze of her stepfather, Herod. In biblical versions, Salome’s mother, Herodias, is insulted by the prophet’s criticism of her second marriage, and encourages her daughter to demand his execution. In Wilde and Strauss’s versions, Salome is her own woman with her own reasons for doing so.

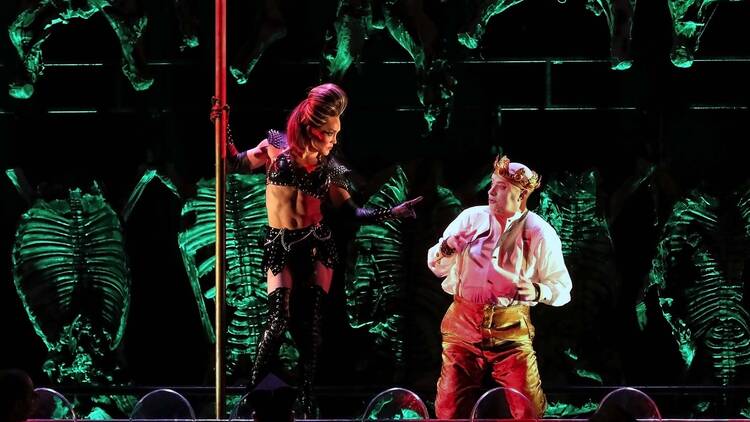

Gale Edwards’ production of the opera premiered in 2012, and explores how male artists have constructed images of femininity over the centuries. It’s most obvious in her approach to the infamous ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’ – her version features a series of dancing women embodying male fantasies of female sexuality: innocent child with teddy, French maid, dominatrix pole dancer, Marilyn Monroe with her billowing white skirt, mother Mary as a saucy go-go dancer – but the male gaze and battles for power are unpacked in every scene.

If anything, Edwards’ approach rings with even more clarity in 2019 – it constantly throws forth questions about gender and the power dynamics at play in Strauss’s opera. Her staging, recreated by revival director Andy Morton, is utterly precise in exposing the hypocrisies of male power.

There’s one particular scene in which Salome stands perfectly still, determinedly making the demand that her stepfather execute John the Baptist (Jochanaan in Strauss’s version). He’s been frantically running about the stage for five minutes, terrified about the implications of ordering the prophet’s death, when he pleads with Salome to calm down, and asks her to look at how calm he is, despite his obvious hysteria. It’s pretty much the operatic version of this recent and prominent image.

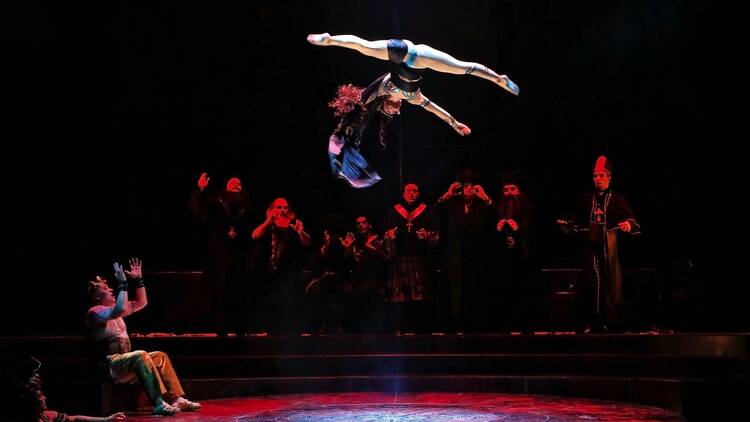

Designers Brian Thomson and Julie Lynch have created a gaudy, anachronistic version of Herod’s court – covered in sparkling, shiny surfaces, and deep reds evoking blood. Along the back of Thomson’s set hangs a series of animal carcasses, glowing bright red under John Rayment’s lighting. Given that Salome has been brought up in a world of such brutality and excess consumption, it’s no surprise that she’d choose to turn that violence upon her lustful stepfather and a holy man who seeks to deny and belittle her.

American soprano Lise Lindstrom is totally at home with her capricious but determined character, who is just coming to understand the extent of her power. She tackles all of the vocal challenges of the role – from its sparkling top notes to the grumbling, demanding contralto-esque bottom – with both force and nuance. Her final scene, performed with a disturbingly realistic severed head, is a lusty, grotesquely realised breakdown.

Andreas Conrad and Jacqueline Dark are an appropriately terrifying pairing as Herod and Herodias – drunk on power and drunk from the lavish feast they’re in the midst of. Conrad brings all of his character’s arrogance to life, while Dark, returning to a role for which she won a Helpmann Award, offers a vocally spectacular, richly textured take on a character who can often be portrayed as just a dragon woman. Alexander Krasnov is a steady vocal and dramatic presence as the soon-to-be-beheaded Jochanaan.

On opening night, the Opera Australia orchestra seemed a little tentative in moments but they certainly found the necessary emotional sweep and drama under conductor Johannes Fritzsch. He draws all of the tension and grandeur out of Strauss’s cinematic score (Strauss wrote Salome before cinema scoring even existed, but he influenced plenty of film composers), particularly in the moments relating to Jochanaan.

In the New Testament, Salome’s story stands as a sort of cautionary tale against the dangers of female sexuality. In Edwards’ version, it’s still a cautionary tale, but instead one about unchecked patriarchal power structures. It also offers a more complex image of Salome than most would allow us to have – she’s neither entirely a victim nor a monster. You might even find yourself cheering for her as she commits a pretty horrifying act. When she tells a sanctimonious holy man that he may have seen his god, but never saw her coming, it’s a pretty intoxicating moment.