When it was announced that Julie Andrews was going to direct a production of My Fair Lady in Australia, lifelong fans started salivating immediately. When she explained that it would be an exact replica of the original 1956 Broadway production in which she starred and made her name, doubts began to creep in. Could you possibly recreate the magic and allure of what was at the time the greatest musical theatre success story ever? And even if you could, why would you? What could a hoary old production, trapped in amber, have to say to modern audiences, even those primed for nostalgia?

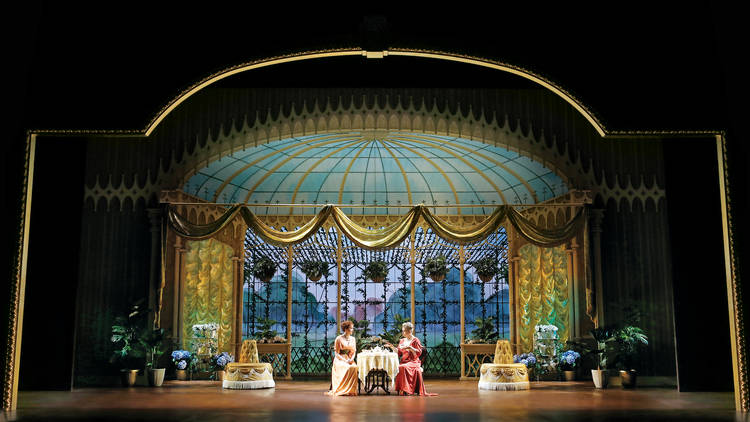

The answers are surprisingly multi-layered, even contradictory. It is, of course, impossible to know exactly how faithful the production is moment by moment without a time machine and a photographic memory, but certainly the sets (Oliver Smith) and costumes (Cecil Beaton) are verifiably precise, and the choreography breaks its back to seem authentic. My Fair Lady had several runs, on the West End and in revivals, and this 60th anniversary production aims to collate all that the designers learnt along the way. It means we have a gorgeous period motorcar that was intended for, but never appeared in, a scene on the road to Ascot. It means we get details, in both the scenic and lighting design, that have been augmented and refined, according to the production’s evolution. If that constitutes a replica, then maybe the concept isn’t so absurd.

Lerner and Loewe’s musical adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion was met with critical disdain, for about twenty seconds. The idea of taking high Shavian culture and mixing it with the low culture of musical theatre may have sounded vulgar to critics of the day, but as soon as they saw the results, they were hooked. Lerner and Loewe’s genius was in seeing the value in urbane and sophisticated banter having to rough it with base music-hall entertainment. The two modes complement each other in undeniable ways, grounding the repartee of the upper class and elevating the rambunctiousness of the chorus.

The tale of Eliza Doolittle (Anna O’Byrne) and her transformation from “common flower girl” to elegant society woman under the tutelage of the impossibly smug and insensitive phonetician Henry Higgins (played here by Charles Edwards, taking over from Alex Jennings, who opened the show at Sydney Opera House in 2016) traces its roots to Ovid, who told of a sculptor who fell disastrously in love with his sculpture. While there are many highly uncomfortable moments of outright sexism in the piece, it’s a mistake to read the play as a misogynist fantasy; while Higgins changes Eliza, moulding her in his image, she changes him just as profoundly. O’Byrne and Edwards navigate the shifting power dynamics beautifully, and the emergent realisation that they’re in love almost breaks down the inherent paternalism of their circumstances. Almost. He’s still an insufferable prick who holds all the structural power, but you get the sense she’s winning serious battles of her own.

While Edwards and Andrews are British imports, the rest of the cast make a satisfying argument for the depth and buoyancy of our local music theatre talent: Reg Livermore makes a happily compromised louse of Alfred P. Doolittle; Tony Llewellyn-Jones is wonderfully vigorous and jovial as Colonel Pickering; Robyn Nevin is faultless as the poised and sensible Mrs Higgins; and Deidre Rubenstein makes a glorious Mrs Pearce, suggesting a deep well of compassion that permeates the Higgins’ household. The leads may be in complete control of the material, but it is the support that gives the production its texture.

The sets and costumes are quite remarkable; there’s no need to imagine what audiences in 1956 must have felt witnessing the grandeur and sheer taste of the double revolve set that transforms from Covent Garden to Ascot to Higgins’ manor and back again. It is every bit as impressive today, and makes many comparable contemporary sets look cheap and ugly (Aladdin, we’re looking at you). Beaton’s costumes are a thing of wonder, most notably at Ascot but impeccable throughout. Richard Pilbrow’s lighting design is rich and powerful, although there were more than a few missed cues and poor transitions on opening night.

The decision to commandeer Julie Andrews to direct this production has payed off handsomely. O’Byrne often seems to be channeling her, which may give audiences an eerie sensation that they’re actually watching Andrews in the role, but paradoxically does nothing to minimise O’Byrne’s personal stamp. Edwards brings all that Rex Harrison brought to the role, only he’s more likeable and conflicted. The strict parameters Andrews has enforced in no way impair the vibrancy or fluidity of the performances; if anything, the actors thrive under them. No one is dull or nonchalant, and those sublime songs hit every time.

It might seem quaint to see a musical that conforms so seriously to the conventions of the form – with its overture and entr’acte, its reprises and repetitions – and yet there is nothing quaint about the result. It’s alive and funny and moving, and makes a powerful case for direction that is in service to the work, instead of work that is in service to the director. Not just a triumph at the ball, this Eliza is a triumph for the ages.

Review

My Fair Lady

Time Out says

Details

Discover Time Out original video