From the moment it was announced that Opera Australia was bringing Cameron Mackintosh’s 2014 West End revival of Miss Saigon to Australia, there has been considerable discourse in the theatre community. The criticism was to be expected – the controversy has its own Wikipedia page – and the musical has a complicated legacy.

Set towards the end of the Vietnam war, the story follows Kim (Abigail Adriano), a recently orphaned teenager taken in by a hustling brothel-owner known only as The Engineer (Seann Miley Moore). On her first night as a sex worker her services are offered to soft-spoken American GI Chris (Nigel Huckle) as an “almost virgin”. Unexpectedly, they fall in love – but a misunderstanding leads Chris to break his promise of taking Kim to America when US forces are pulled out of the country. Kim is left in Vietnam to await Chris’s return and care for their son, whom Chris is unaware even exists. Ultimately, she gives up her child, believing that only America can give him a life worth living.

This production is a visual delight offering strong performances that are sure to make these actors stars...

If the story sounds familiar, it’s because it’s based on Puccini’s equally controversial 1904 opera, Madama Butterfly (which Opera Australia also recently staged on Sydney Harbour to critical acclaim). Created by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil, who are predominantly known for Les Misérables, Miss Saigon debuted on the West End in 1989. With its tragic, doomed love story and layered, expansive score, the show has garnered plenty of fans over the years. However, since its inception, it has also garnered criticism for its harmful perpetuation of “orientalism, racism, and sexism”.

From a technical perspective, this production is a visual delight offering imposing sets, majestic lighting and choreography and strong performances that are sure to make these actors stars, but the issues with Miss Saigon and the western theatrical landscape that hang over this production cannot be ignored. There is a longstanding debate about whether classic musicals, often a product of their time, should be judged by the values of contemporary society. Traditionalists will insist that those who demand a modern reckoning “miss the point”, which disregards the way that art, in particular “the classic” has been used for centuries – as an ideological weapon to shape the self-image of the colonisers and the colonised. It assumes that a production has no moral responsibility for the power it has to infiltrate popular culture, impact attitudes and behaviours, and influence unconscious biases.

Others believe that productions can be updated to better serve the communities which they have historically harmed. South African production director Jean-Pierre Van Der Spuy is one such believer, and he and the Australian production team have done their best to modernise this story steeped in American propaganda.

Drawing on his experience in South African apartheid protest theatre, Van Der Spuy is sensitive to challenges of portraying real events and the show’s propagandist elements, which position white Western culture as superior to Vietnamese and Asian cultures more broadly.

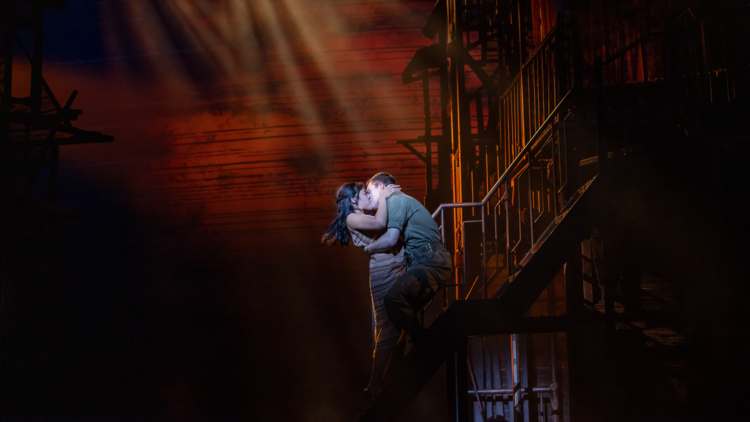

As a result, this revival lingers over the atrocities of war and the destruction it leaves behind, with an emphasis on the damage caused by US forces. The famous helicopter scene in which Chris leaves Kim behind stands out here. An arresting accomplishment of stagecraft, it is lit immaculately by Bruno Poet and features video projections by Luke Halls that transport the audience to the harrowing moments before and after a country loses its lifeline. These moments, and the preceding scenes that show the lines of desperation at the American Embassy, are dripping with white guilt but hold their relevance for a modern audience, presenting stark visuals that could easily mirror real-life scenes from Afghanistan and Syria in recent years.

There is only so much that can be changed in a touring production that is almost a decade old, and the resulting amendments are too subtle...

To try and improve this production's sensitivity, Van Der Spuy has brought on Vietnamese-American resident director, Theresa Nguyen, and engaged several cultural consultants across music, casting, language and production. As a result, there is thankfully no prosthetics in use (as in the original production) and many Asian-Australian actors and performers from across the Asia Pacific are given the opportunity to shine.

The cast is exceptional, and given the dearth of dimensional lead roles for Asian Australians, it's unfortunately not a surprise to learn that for many of them, this production is their debut. It’s no secret that Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil’s music, along with the late William David Brohn’s orchestration, is impressive, and this cast meets this hefty score with skill and gumption. Adriano delivers boundless desperation in ballad after ballad as she clings to Huckle’s Chris – their intertwining, intimate melodies emphatic, creating spine-tingling chills. Vietnamese words are used in Chris and Kim’s betrothal song, which was originally written as non-sensical gibberish, but the arrangements otherwise remain the same. Much like in Schonberg and Boublil’s Les Mis, the soaring arrangements are the most impactful part of the show.

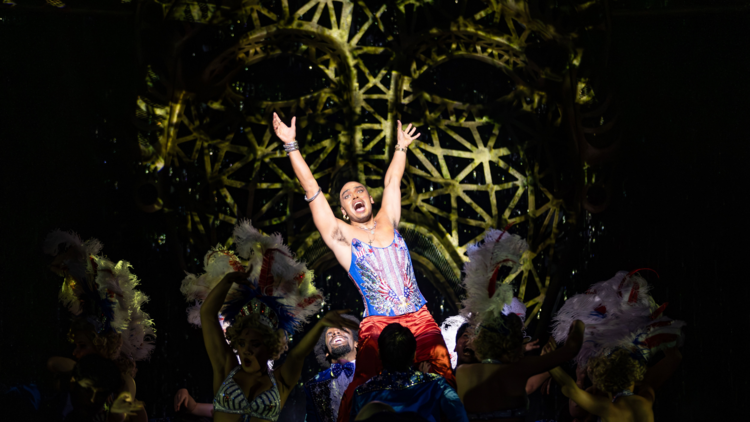

Van Der Spuy most markedly puts his stamp on this production through the casting of Filipino-Australian singer and The Voice alum Seann Miley Moore who brings queer, camp excellence to the role of The Engineer. Miley Moore leans into the lascivious pansexuality inherent in the renegade swindler, pushing the character beyond a misogynistic sleaze to a flamboyant masochist who craves the extravagant materialism only white privilege can bring. This expression of queerness increases the stakes for a character that has often been dismissed as a mere caricature, a projection of colonial views of eastern barbarism.

It’s a somewhat fresh interpretation of The Engineer that is a far cry away from the prosthetics and yellowface that has haunted this characters’ past. However, it begins to feel dissonant from the rest of the show as this liberation, self-righteousness and empowerment is not extended to Kim, or seen in scenes that depict the sexualisation of Vietnamese and Thai women.

There is only so much that can be changed in a touring production that is almost a decade old, and the resulting amendments are too subtle, too contained or too internal to lead to any real modern reckoning.

Consider the opening number, ‘The Heat is On in Saigon’, set in a brothel and historically fetishistic, this production attempts to veer away from orientalist costumes that exoticise Asian women with the male gaze. There is also a broader range of body types represented, which is welcome, but ultimately the women are portrayed as destitute, subservient and in need of saving by the strong, masculine white men of the “superior” West. These surface level choices can only go so far.

Laurence Mossman makes an astounding debut as Thuy, the man to whom Kim is betrothed, and who she repeatedly rejects. He delivers pained, deep and controlled vocals, but is limited by a production that has constructed him as violent, exploitative, cruel and possessive. He is the antithesis to Chris's love, undeserving of sympathy – a distillation of the show’s politics that sees all-American values as good and all Asian ideology as bad.

Chris’s American wife Ellen (Kerry Anne Greenland) is the only female character portrayed sympathetically, even receiving a new song, 'Maybe', in this revival to make her more likable – because we couldn’t possibly have a musical where the white woman isn’t liked, could we?

When it comes to giving Miss Saigon a thoroughly modern makeover, this revival is more try than triumph. It continues to reinforce ideas that are already too comfortably held in a post-colonial society, that the East and the West are opposing entities and as a result non-Western nations are unsophisticated andin need of saving. It similarly sends a strong message to Asian audiences, that their survival is conditional to their conformity to the white way. However, its majority white audience will be able to enjoy the spectacle of the production. They are protected by the privilege of not identifying with the destitute Asian woman that no-one would aspire to be.

With the Sydney theatre landscape exploding with Asian talent in works like Michelle Law’s Miss Peony and Anchuli Felicia King’s The Poison of Polygamy, let’s hope this is the last time we have to rely on an outdated ostentatious revival to make sure the talented Asian-Australian creative community is given the opportunity to shine.

Miss Saigon is playing at the Sydney Opera House until October 13, 2023. Tickets start from $75 and you can get yours over here.