In early June of 2020, playwright and actor Meyne Wyatt delivered a performance on ABC’s Q&A that was hailed as a watershed wake-up call to the reductive ways First Nations people are misrepresented and commodified through the white gaze. This blazing monologue, an excerpt from City of Gold, became an instant viral moment, not only for the content's raw truth but also for its delivery's gut-punch power. But as urgent and sobering as this speech is in isolation, it gains an extra dimension of emotional heft within the context of the story from which it's lifted.

Wyatt’s debut play, which premiered in 2019 at Sydney’s Griffin Theatre before touring across the country, offers the experience of a grieving family as the microcosm to unlock a much broader discussion about identity and discrimination. Preservation of culture, the struggle to hold onto country and community, and the myriad entrenched systems of violence and mistreatment faced by First Nations people are brought into harrowing focus through the fractious relationship of three siblings struggling to cope in the wake of their father’s death.

The play opens with a warped vision of Aboriginality, a figment of colonial myth that still persists as true blue Australiana today. Breythe Black (Wyatt) is an actor on the set of an ad promoting lamb for Australia Day barbies, spear in hand and a canoe at his feet. While the storyline claims to be about unity and reconciliation, its hamfisted imagery is offensively white-washed. Breythe is attempting to explain this to the obtuse director when he receives the call that his father (Trevor Ryan) has passed away after a long, painful battle with throat cancer.

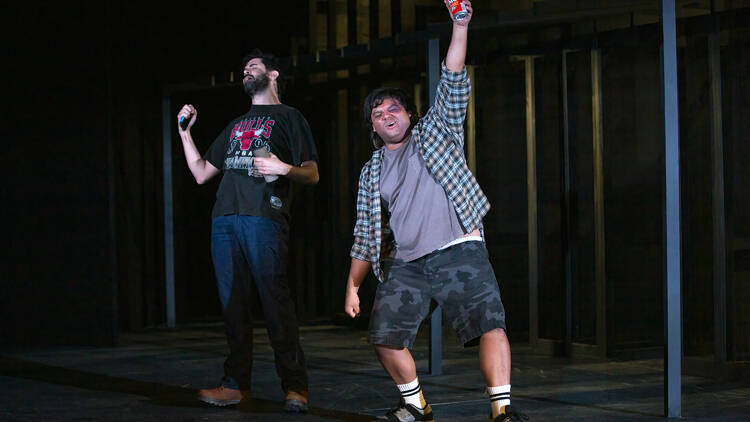

Returning home to Kalgoorlie, he finds his family – brother Mateo (Mathew Cooper), sister Carina (Simone Detourbet) and cousin Cliffhanger (Ian Michael) – reeling from the loss, each relying on their own sometimes destructive ways to cope. Old grudges bubble to the surface, particularly Mateo’s resentment towards his brother’s chosen profession. But in a town where police brutality and racial hatred keep the threat of violence constantly at their doorstep, Breythe must find a way to overcome the grief and guilt that is driving his family apart.

Director Shari Sebbens (The 7 Stages of Grieving, Seven Methods of Killing Kylie Jenner for Darlinghurst Theatre), who played the role of Carina in City of Gold’s premiere season, has stripped the backdrop of this Sydney Theatre Company production to its most gestural forms so that the performances of her cast carry the full weight of the narrative. Such a minimalist set also removes any sense that Kalgoorlie is somewhere remote, somewhere elsewhere, that audiences may feel conveniently removed from. This community could be literally any in Australia. The discrimination this play explores can and does exist in every city, town and village. This isn’t outback Australia or rural Australia or desert Australia. It is the Australia we all live in, right here, right now.

Wyatt’s semi-autobiographical script is a masterful feat of storytelling. There is such easy finesse in the finely drawn family relationships, such effortless understanding of how to make dialogue both beautiful and credible. There’s humour where it’s needed without it feeling glib, and loving, intimate moments that resist becoming sappy. The play’s most surprising sleight of hand is the way it manipulates past and present, memory and dream, to quietly unmoor us from a linear narrative without us even realising. It is a text that is artful yet gritty, that pushes its emotional cadences to extremes while keeping us rooted firmly in reality, and while it refuses us the catharsis that we might well crave at its heart-shattering climax, it does so deliberately, knowingly, to make its final, graphic image all the more unignorable.