Tennessee Williams helped shape the direction of American theatre, coming along in the middle of the last century to fuse national concerns with the deeply held, often repressed lives of individuals and families. His works are preoccupied with shame, failure, connection, intimacy, loss and regret. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, a portrait of a family falling apart that’s arguably best remembered now for the 1958 film starring Liz Taylor and Paul Newman, is dripping with high, emotional drama.

Because it’s so full of confessionals, confrontations and showy despair, it’s a play actors can really sink their teeth into. It makes sense, then, that in Kip Williams’ overwrought new production for Sydney Theatre Company, the cast is the main event. It’s the best thing the play has to offer a 2019 audience, and if you like actors making a meal of scripts, you might just like this staging: at one point, for better or worse, a character actually cries out “noooooooo!” as a scene reaches its dramatic climax.

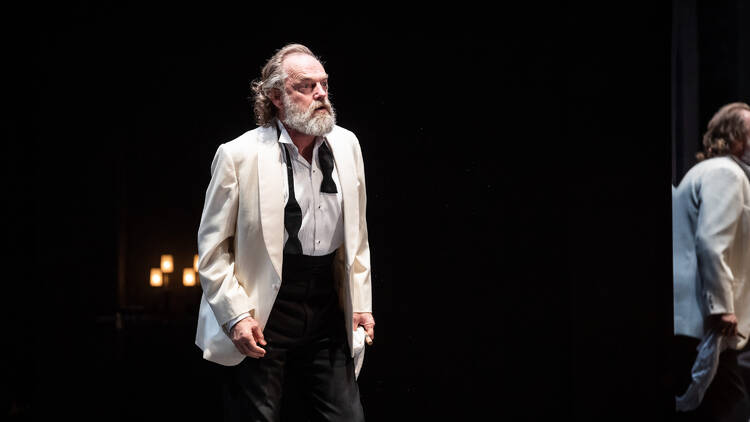

So it’s a good thing that there’s a good cast on board. The great Hugo Weaving plays Big Daddy, the family patriarch who, on his 65th birthday, is reckoning with what might soon be the end of his life. Weaving is a full-throated roar in the role, and he tears through the script with conviction. His wife, Big Mama, is Pamela Rabe, a grande dame of the Australian stage. Rabe brings that status and reputation with her; even though Big Mama is ridiculed by the family, Rabe has her clinging to her dignity. Weaving’s own son, Harry Greenwood, takes on the role of favourite son Brick, who developed a drinking problem after his best friend, and probably the love of his life, died by suicide. His wife Maggie the Cat, played by Zahra Newman with tenacity and open-hearted accessibility, knows about her husband’s secret feelings but can’t bring herself to leave him. However, she wants more from her life, and she isn’t afraid to demand it.

It’s a lot of crying, fighting, challenging and dramatic collapses on the floor. More than a lot: it’s too much. Set in a hyper-modern, abstract and endless space (designed by David Fleischer), Williams’ production is so overtly emotional it seems to have traded more practical aspects of play-making, like clarity of purpose and theme, in favour of more rangy, melodramatic exchanges that criss-cross the massive stage. The set is at odds with the suffocating family dynamics in the play – there’s too much artificial space and slick marble for us to feel as trapped in it all as the characters do. With internal logic ranking behind big character moments, these big dramatic scenes, rolling out one after the other, begin to flatten out and become dull.

A drumbeat (music and sound by Stefan Gregory) thrums ominously and heavy-handedly in the background whenever Brick’s repressed sexuality comes up in conversation. In the background of all the action, distant sounds of party poppers and celebratory cheers arrive discordant and twisted to remind us that all isn’t well (and that over the course of this play, we’re supposed to be at a party).

There’s not much in this production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof that makes the play feel like a particularly vital work for 2019. Its ideas – that the great American dream is a sham, that we live in a society built on lies and unfairness, that queerness needs to be exploded out from silence – are all enduring ones, but it’s hard not to hunger for a work that tackles these problems with a less dated perspective. Even if that means not hearing the poetic, evocative words of a mid-20th century master.

Still, a theatre company produces work to entertain and engage audiences, and Williams is beloved, and there’s something, perhaps, in letting good performances justify the production existing in the first place. And there’s a lot of good acting work here from the principal cast, or at least a lot of showy, chewy acting, that you can get swept up in.

Even though very little about this production is small, the best moments are small ones: spiky, well-timed comic assists by Peter Carroll as Reverend Tooker and Nikki Shiels as Mae, the wife of Big Daddy’s lesser-loved son Gooper (Josh McConville). A passel of rowdy redheaded children running through scenes purely to disrupt them, and they’re charming every time. A moment where Maggie looks at herself in a mirror, trying to understand herself. These small instances keep the humanity of the play alive, and keep us connected to it.