With waves of folks let go from the hospitality industry in one fell swoop, it’s hard to look past those devastating headlines. But it’s not just our cafes, bars and restaurants that have shut up shop indefinitely. The arts are smarting too, with music venues, in particular, falling silent.

Festivals and gigs have been cancelled for the foreseeable future. Venues and music rooms are shuttered with no concrete return date. Jobbing musos have seen their day gigs in hospitality, retail and the service industry disappear in a puff of hand sanitiser too as the lockdown kicks in.

Still, musicians are a resourceful lot, and many have pivoted remarkably quickly to the notion of live-streaming gigs to a now-housebound audience. Isol-Aid, a two-day virtual festival organised by Melbourne artist Rhiannon Atkinson-Howatt, was a recent example hosted on Instagram. Some 74 artists including Stella Donnelly, Angie McMahon, Didirri, and Julia Jacklin played 20-minute sets from their respective homes, tagging the next artist on the roster so fans could follow along.

Isol-Aid is the biggest cyber-festival to take place since the virus outbreak, but many more of varying scales are sure to follow, with smaller sets already cropping up. On a global level, Sofa King Fest is aggregating live gig stream from around the world, with the likes of Willie Nelson, Melissa Etheridge, Cypress Hill, and more playing for homebound, and Mary’s Group curating the Australian contingent for the site.

Locally, Surry Hills Live was already promoting live gigs at the Strawberry Hills Hotel and the Shakespeare Hotel, in collaboration with Music for Trees and with funding from the City of Sydney, when the hammer came down. They quickly pivoted to an online platform.

Dean Francis of Surry Hills Live explains, “On Monday last week, it became pretty clear that we weren’t going to be able to keep doing that as the bands weren’t going to play, the pubs weren’t going to open. So, we already had the shooting infrastructure up and we very quickly figured out how to live stream.

Luckily their production office in Surry Hills has a basement, which Francis says, “is a suitably apocalyptic backdrop, and our neighbourhood has recently been fitted with 5G, so it was basically realising that we had most of the tools we needed and we just needed to upskill in a few areas.”

They hosted their first show, with blues artists Jesse Redwing and Kane Muir, on March 19, with Machine Gun Fellatio mainstay Christa Hughes earmarked for the next gig on March 26.

Musician Michael Burrows was facing the prospect of being unable to promote his latest release, single ‘Please Don’t Cry’, on the live circuit – a particularly bitter blow considering he made it in collaboration with one of his artistic icons. “I’d just released a song with Neil Finn, one of my musical heroes, singing on it,” he explains. “So, he’s singing on my record, and everything is just swimming along, and then bam!”

Regrouping, Burrows founded the Facebook page Gigstream, a resource for musicians to live-steam gigs where audiences can find them. It’s a labour of love.

Elsewhere, the Covid-19 pandemic has inspired nascent music streaming projects to move up their schedules. The brainchild of Powderfinger’s Ian Haug and Natalie Sim of film production company Method to My Madness, Up in the Airlock was inspired by NPR’s Tiny Desk Concerts and KEXP Live. The original plan was to start streaming shows from Haug’s Airlock Studios around May.

That changed pretty quickly. “We thought we could help support musicians and creatives by expediting the production,” Sim explains. “We want to do our small part, entertain and introduce people to some new music when no one can physically go see live.”

Hence The Quarantine Sessions were born, with Brisbane band WAAX having the honour of being the first band to perform on that platform on April 9, kicking off a first “season” projected to last for three months. The sessions are free to watch on YouTube.

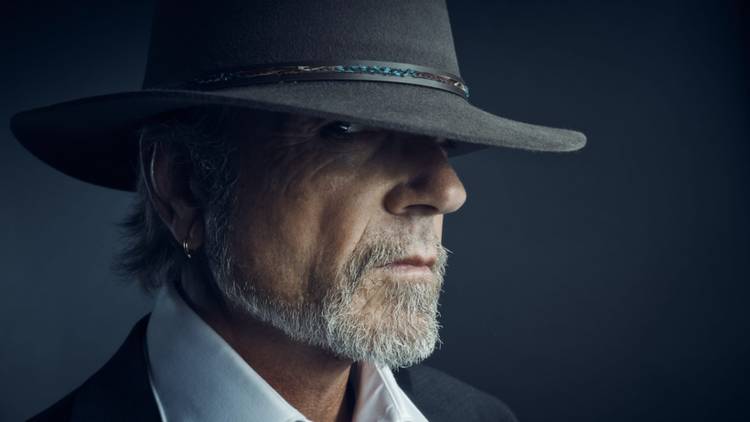

The legendary Steve Kilbey (pictured), Haug’s bandmate in The Church, also got in on the act, live-streaming a gig on Instagram on March 23. “I was sitting around feeling really bored and not receiving the adulation to which my ego has become accustomed,” he jokes (we think).

In truth, facing a suddenly empty touring schedule, Kilbey has embraced the prospect of connecting with his audience online, enabling a Paypal tip jar during the live feed, but is doubtful the financial possibilities stack up long-term. “I’ve had literally a hundred shows cancelled overnight,” he says.

Free does seem to be the dominant model for live gig streaming at the moment, which does raise a somewhat awkward question. It’s all very well connecting artists with their audiences, but how do they pay the bills?

Culturally, we’re accustomed to free or nearly-free digital content, and while pointing punters to Bandcamp pages and merch sites can bring in a trickle, it’s not going to match pre-pandemic gig incomes. Right now, streaming gigs are a show of solidarity and community – but can they also be a viable revenue stream for artists?

Kilbey, ever ambitious, has an answer, if not necessarily the appropriately isolated one. “I’m thinking of taking it a step further and having people come to me. If someone wants to pay two or three grand, I’ll have them round my house, set up a chair at one end of the room, and I’ll play at them from the other end.”

A one-man Church concert. We are living in strange times.