[category]

[title]

It's an exciting part of UNSW Galleries' queer exhibition Friendship as a Way of Life

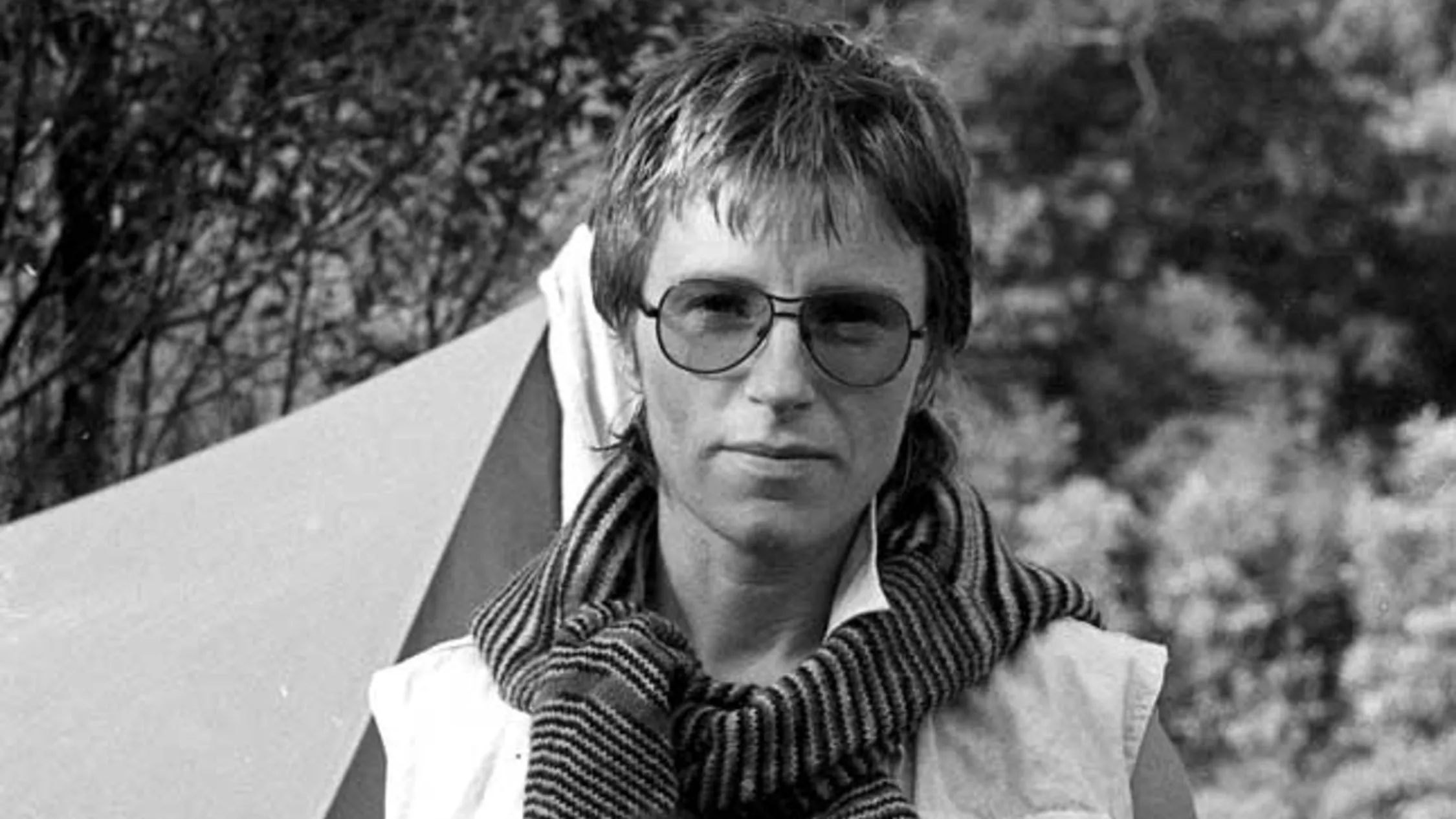

When you think of the queer history of Australia in 1978, chances are you immediately think of the very first Mardi Gras protest and the earthquake it unleashed. Artist, filmmaker and academic Helen Grace, a young mother at the time, wasn’t on the march that day, though she did photograph the brave souls who fronted court after being arrested. But Mardi Gras wasn’t the only queer story worth documenting that year.

Grace also headed into the remote Northern New South Wales mountains to capture staggering black-and-white portraits of the occupants of a radical feminist lesbian separatist community known as Amazon Acres. Unseen for some 40 years, 12 jaw-dropping examples from that powerful portrait series are finally receiving the attention they deserve as part of UNSW Galleries exhibition Friendship as a Way of Life. The series is called ‘And Awe Was All That We Could Feel’.

“It’s a line from an Emily Dickinson poem about a storm, and it seemed to me to encompass the feeling of that time from the '70s, and how the lives of unsophisticated, country girls, as I was, were transformed by feminism," Grace says.

Raised in country Victoria, Grace eventually came out and moved to the UK, where she fell in with a different strand of feminism from the Amazons, one informed by socialism and Marxism. Moving back to Sydney and living in a feminist collective with a daughter of her own, she was invited to Amazon Acres by friends who lived there.

“I should say at the outset that I’m not actually the keeper of the memory of those places, because I was just a visitor,” Grace says. “By that time it was a world I’d moved away from. I did really like washing machines, because I had a young child and the last thing I wanted to do was to wash nappies in a creek.”

But she admired their fierce freedom. “This imaginary ideal world that was being built, it was a great social and personal experiment, because all those norms of nuclear families, monogamous marriage, general straightness, all that was being challenged. And I was really interested in that challenge and the heroism of the women, who I thought were these kind of terrifying Amazonian figures.”

Back then, Grace was overwhelmed. “I was a very shy, reticent sort of person, but I did have friendships which I still have with some of those women who made a life of it, so I would say that I was a little bit invisible.”

All the better for capturing these startlingly candid shots. “I was very interested in photographs that were of the everyday and what we take for granted,” she agrees. “But also recording a historical, exhilarating moment too.”

Which makes it all the more amazing that they’re only just being seen by the public now. That’s partly because Grace wasn’t sure she had anything worth showing. It’s also because there was no spare money to print gallery-ready shots, nor many galleries at the time that would be interested. Even as queer art became more prevalent, the focus was usually on gay men. “There’s a rich history of lesbian art and collectors, but it’s often overlooked,” she says.

Grace was part of the push to have “lesbian” added to the official Mardi Gras title. Her pictures of the courtroom drama after the very first protest caught the eye of Friendship as a Way of Life co-curator José Da Silva when they were finally displayed at Bondi Pavilion in 2018, to mark the 40-year anniversary. He invited her to join the UNSW Galleries show, and they whittled down hundreds of Amazon Acres images to the dozen displayed.

Grace sees their worth now. “Suddenly they look remarkable in a way that they didn’t at the time, because they were precisely about what’s being taken for granted and not even seen. That’s a big aspect of photography. I often think I don’t know what I’ve got for another 30 years. There’s something about the intensification of time passing. And so now I go back and them I don’t see them so much as images of the past, but possible futures.”

And is she still on the front line of the kind of queer Marxist feminism that gives shock jocks and right-wing columnists the willies? “You know, you reach an age where you have to pull back a bit and hand on to the next generation while doing what you can to help. I’m still engaged in that those ideas, very much, but it’s now defined by young women today, and I trust the direction that they will take us.”

But she does think it pays to reflect on the achievements of the past, and what was won but has now been lost. “In a certain sense, it’s kind of being rerun. Women are still economically worse off than men, and the situation is far worse now than it was 40 years ago in terms of resources.”

Structures still need dismantling, Grace suggests. “Even today, if we’re to change everything, then we are going to have to examine our own comfort and become a little bit more uncomfortable.”

Friendship as a Way of Life is at UNSW Galleries until November 21.

This article is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas

Discover Time Out original video