At first glance, there’s not all that much connecting the two parts of Sydney Dance Company’s latest double bill. One feels lavish and expected, and the other feels brittle, sparse and satisfyingly surprising.

The first piece is a revival of Rafael Bonachela’s superb Frame of Mind, which premiered back in 2015. It’s very much core territory for the company – beautifully athletic and inventive contemporary dance set to a wrenching score composed for a string quartet by Bryce Dessner.

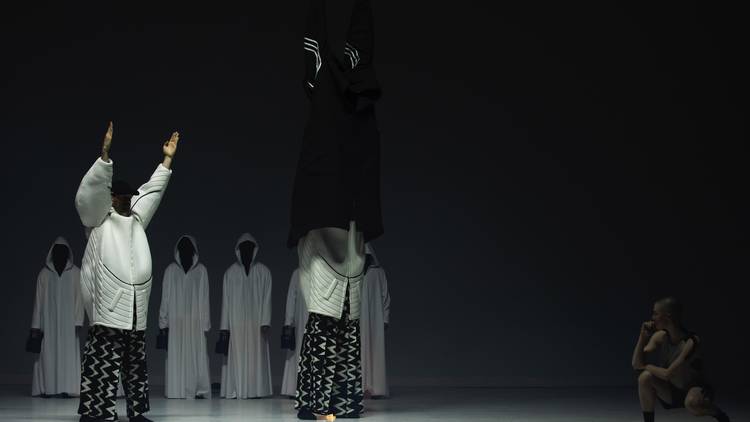

The second, called Forever & Ever, is a dark and intoxicating new work by Antony Hamilton that often seems as much like an installation as it does a dance piece, inspired by fashion, nightclubbing and electronica.

It starts with Jesse Scales performing a solo in total silence, activating body part by body part as she moves around the stage in an intricately choreographed and tightly wound routine.

She then picks up a light that’s been sitting on the stage, and the music suddenly takes over the theatre. Composed by Hamilton’s brother Julian (who’s one half of the Presets), the score features a near constant rhythm that hypnotically repeats for almost the entire 35 minutes of the performance as a simple synth soundscape evolves around it. It’s as if you’re reaching the end of a night in some underground Berlin club.

A line of figures in giant black cloaks slowly approaches Scales, like a centipede, waving white cones through the air. The towering figure at the front of the line (Izzac Carroll) dwarfs Scales in a physical sense, but their relationship would appear to be on a much more even footing, as Scales almost seems to direct him about the space and uses his body to hoist herself above the ground.

Then the layers begin to peel back, in a literal sense (and there’s the most theatrical removal of a coat you could possibly imagine), and the figures become more human. And each of them seems to have a double, dressed and styled in the same way, performing moments of unison. Then those layers strip away to reveal basic blacks, bringing the ensemble together as a single group.

Paula Levis’s costumes are Berlin streetwear via Gareth Pugh and Alexander McQueen, and are essential to Hamilton’s perspective. So too is Benjamin Cisterne’s lighting, which uses sudden bursts of colour to propel the dance forward. And lasers. Yes, lasers.

It’s an inventive and adventurous ride, and the choreography is original and evocative enough to stand up to the theatricality of the design. But it’s also the sort of piece that some contemporary dance fans may find a little too tightly constricted to showcase the full talents of this astonishing company. For those audience members, there’s Bonachela’s work, which was created when he was longing to be in two places at once.

Dessner’s score moves at a frantic pace for the most part, matched by Bonachela’s choreography that pushes the dancers in both emotional and physical ways, with the intensity of full ensemble pieces offset by tender solos and duets.

There’s excellent work from Nelson Earl, who has a gorgeous solo, and Jacopo Grabar, who is brand new to the company. The entire work throbs with the sense of longing that Bonachela writes about in his program note – for connection, to be seen and to have our emotional needs met.

And that’s really where these two works cross over – both interrogate who we are as individuals and how we shift and evolve when part of a collective. There’s an extraordinary artifice and tough edge to Hamilton’s vision, but it’s also entirely about the way we’re connected as humans; how we’re drawn together by gesture, fashion, music and dance. In that sense, these two pieces are more alike two sides of the same coin than you might suspect.