One of art’s most famous anecdotes sounds like a joke. Three artists – Léger, Brancusi and Duchamp – walk into the 1912 Paris Aviation Salon. Here, they are gobsmacked at the sheer beauty of the huge airplane propellers on display. “Painting’s washed up,” Duchamp says to his companions after a moment of silence. “Who’ll do anything better than that propeller? Can you?”

The story resonates because Marcel Duchamp was as good as his word. Not only did he more or less abandon his nascent, successful painting career, he went on to originate the idea of ‘readymades’ – existing objects elevated to the status of art through virtue of being ‘selected’ by the artist.

“As the story goes, the propeller presented Duchamp two options,” says Nicholas Chambers, senior curator of modern and contemporary international art at the Art Gallery of NSW. “Continue down a very conventional path, or change the rules and invent, from scratch, an entirely new way of being an artist.”

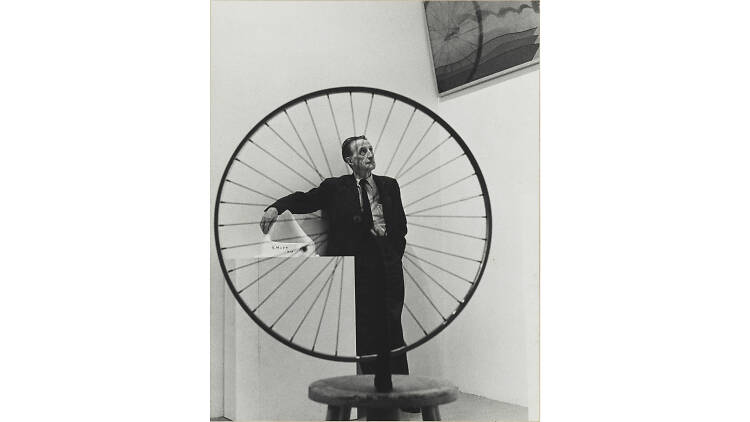

Duchamp went on to create game-changing works like ‘Bicycle Wheel’ (1913) – a wheel attached to a chair – and ‘Fountain’ (1917) – a store-bought urinal inscribed with the facetious name ‘R Mutt’. The official mid-20th century reproductions of these lost works are at the centre of The Essential Duchamp, the largest exhibition of Duchamp’s art to be shown in Australia, opening at the AGNSW on April 27.

As the show makes clear, there was more to the French-born American than simply signing things and calling them art. As well as laying the groundwork for conceptual art, he popularised the idea of made-up artistic personae, adopting the pseudonym ‘Rrose Sélavy’ from 1920 onwards. He made sculptures and films, designed exhibitions, produced optical and text-based works, designed products and created boxed sets compiling his notes and supporting materials.

“In a pretty fundamental way, he changed what we mean when we use the words ‘art’ and ‘artist,’” says Chambers. “He famously said that he wanted to ‘stop making retinal art’ – art that was essentially there to please the eye – and instead put art in the service of the mind.”

The show comes primarily from the holdings of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which was gifted the collection of Louise and Walter Arensberg in 1950; Duchamp worked closely with the Arensbergs to ensure his legacy was protected. Hence the show is able to span Duchamp’s teenage paintings, his dabblings with post-impressionism and Cubism in the 1910s, his radical diversions later that decade, all the way up to the 1960s.

Duchamp’s work has not been seen in Australia for more than 50 years and the exhibition provides a unique opportunity to come to grips with an artist without whom, arguably, many of the movements of modern and contemporary art could not exist. Campbell’s soup cans? Picture of a pipe labelled ‘This is not a pipe’? Cindy Sherman’s self-portraits? Shark in a tank? You can arguably thank – or if you prefer, blame – Duchamp.

“As iconoclastic as Duchamp may have been, each of his innovations have ultimately served to expand the field of art,” says Chambers. “It’s not as if traditional art forms, like painting and sculpture, are irrelevant after Duchamp, but the possibilities for them change, and we can’t look at them in the same way anymore.”