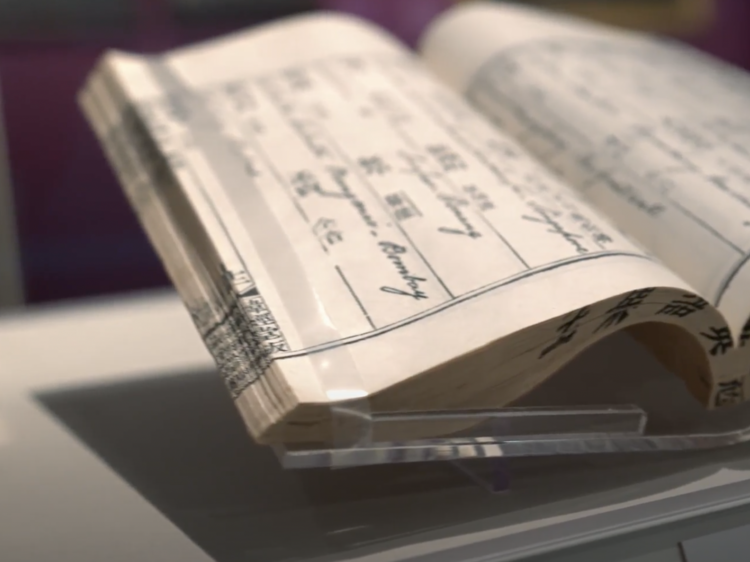

The Chinese and English Instructor

WHO Clement Onn. Principal Curator, Asian Export Art and Peranakan at Asian Civilisations Museum

Can you give us a brief introduction of the artefact?

Phrase books like these helped Chinese merchants and

compradors (agents for foreigners) deal with the

increasing presence of English-speaking foreigners in

Guangzhou and other port cities in the 19th century. The

different volumes are organised by topics. There are

situational dialogues useful in commercial exchanges.

Negotiations over hiring, chartering, renting, inventory

checking, and so forth are listed in detail.

The text was written by Tang Tingshu, a comprador in

Guangzhou. He compiled it in response to the frequently

asked questions that arose during his time working with

foreign traders at Jardine, Matheson and Co., the largest

foreign trading company in Asia. They traded in opium,

cotton, tea, silk, and a variety of other goods.

What insight can this give about maritime trade in the region?

We are living and working in a technologically advanced, modern, and globalised society. When we think about international business and dealing with business partners who might not speak a common language, we have the convenience of smart technology today that could instantaneously translate an email or a social media post at a high degree of comprehensibility. Nonetheless, a good interpreter or someone who is well versed in the required languages is still extremely important to build relationships, eliminate ambiguity and to deal with matters that could be lost in translation. These phrase books are extremely practical, and they gave a sense of how people communicated for business in the mid-19th century. Such business scenes would be very similar during 19th and early 20th century Singapore.