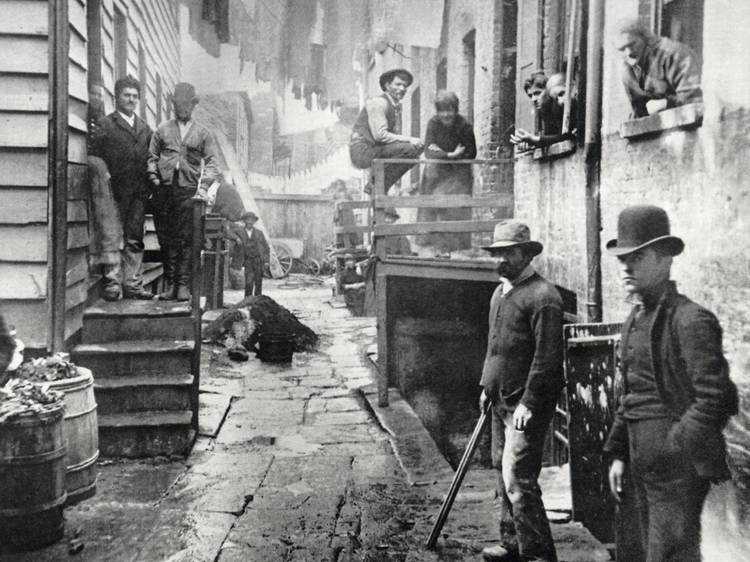

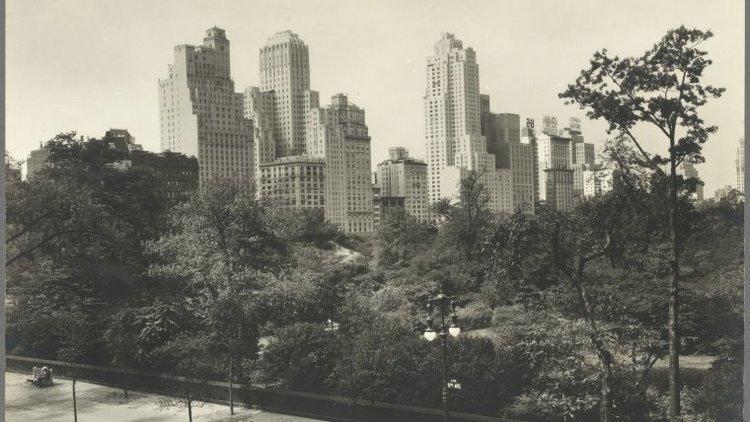

New York’s parks may look pretty and innocent now, but don’t be fooled: from Prospect Park to waterside hangout Riverside Park, the city’s green spaces have been the site of all manner of less-than-legal dealings, tragic deaths and scandalous happenings—not to mention strange bohemian goings-on. Nobody ever said NYC’s history was all sunshine and flowers, right?

RECOMMENDED: Find more on NYC parks

Discover Time Out original video