Theater review by Adam Feldman

The defense never rests in Aaron Sorkin’s cagey adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird. That the play exists at all is an act of boldness: Turning Harper Lee’s 1960 novel into a play in 2018 is far from easy. The hero of the story is Atticus Finch (Jeff Daniels), a lawyer in rural Alabama in the early 1930s, who bravely defends a disabled black man, Tom Robinson (Gbenga Akinnagbe), against a false accusation of rape. Slow to anger and reluctant to judge—“You never really understand a person,” he says, “until you climb into his skin and walk around in it”—Atticus is a paragon of that most fabled of American values: decency.

But while To Kill a Mockingbird has a special place in the literature of American civil rights, the book is also now a minefield. As seen through the eyes of his preteen tomboy daughter, Scout (Celia Keenan-Bolger), Atticus is very much a white-daddy savior, albeit one who can’t perform miracles, in a narrative that has little room for the perspectives of black people beyond the respect and gratitude they show him. At its center is a story about a young woman—Tom’s accuser, Mayella (Erin Wilhelmi)—whose allegations of sexual assault must not be believed. Even more problematic, to some modern ears, is the scope of Atticus’s magnanimity. It is not just the black skins that he urges his children to walk around in; it is also the skins of the white farmers who try to lynch Tom Robinson before his trial. Atticus’s humanism can sound, at times, like an evasion of moral distinction.

That isn’t quite fair to the Atticus of Lee’s book, who dismisses any white man who cheats a black man as “trash.” But it’s a question about which Sorkin’s play seems acutely alert and, well, defensive. Having survived a legal challenge from Lee’s estate, which believed that it departed too much from the novel, the play has its guard up. (In a departure from normal procedure, the production did not provide critics with a copy of the script.) The play does not think that there are fine people on both sides, and it wants to plant a flag on the right one.

“They’re still good people,” Sorkin’s Atticus says of the racists in his town. “They’re still our friends and neighbors.” But the storytelling doesn’t back him up. Sorkin has made the villains—especially the odious Bob Ewell (Frederick Weller), the accuser’s abusive father—more villainous than ever; factors that might mitigate our revulsion toward the meaner characters, such as illness or extreme poverty, are downplayed. Meanwhile, Atticus’s attitudes are challenged in explicit terms by his truculent young son, Jem (Will Pullen), and by his staunch African-American maid, Calpurnia (LaTanya Richardson Jackson), whose role has been beefed up substantially from the novel. When Atticus says, “I believe in being respectful,” Calpurnia is ready with a rejoinder: “No matter who you’re disrespecting by doin’ it.”

The play’s ambivalent approach to Atticus is satisfying but also sometimes glib: It’s as though after Anne Frank said, “In spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart,” someone chimed in to add, “Well, except the Nazis.” And despite Sorkin’s best efforts—as is often the case with sensitive material—every righteous decision engenders new potential critiques. The story’s white male protagonist may be in need of an education, but his white male perspective is more central than ever: Scout now shares the narration with Jem and their friend Dill (Gideon Glick), and the major adult women in the story, other than Calpurnia, have been written out. Even Calpurnia, in a way, is less of a character than she was before, and more of a device; you don’t get a strong sense, as you did in the book, of a black woman negotiating her delicate position in the South of the 1930s. (The play’s worst scene finds Atticus explaining to her, anachronistically, what “passive-aggressive” means.)

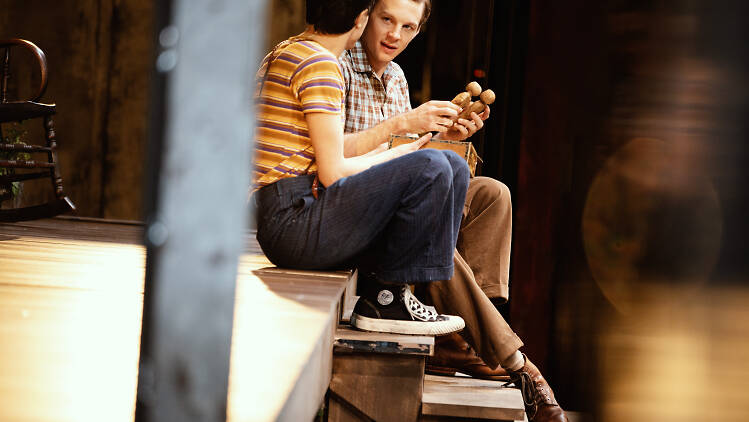

Yet the effort is commendable, and the execution is exemplary. Directed by Bartlett Sher, the elegant production is stately but not stodgy; Miriam Buether’s simple set has just enough detail to suggest the outlines of a memory. (Jennifer Tipton’s lighting and Ann Roth’s costumes help flesh it out.) Daniels is a first-rate Atticus: thoughtful, patient, gently authoritative and appropriately troubled by the unchanging world around him. Three excellent adult actors—Keenan-Bolger, Pullen and Glick—play the child characters-cum-narrators without preciousness, and Wilhelmi is heart-wrenching as the broken Mayella. The large, adept cast also includes Dakin Matthews as a sympathetic judge, Stark Sands as a canny prosecutor, Danny Wolohan as a frightening recluse and Neal Huff as a man who finds limited cover behind his reputation as a drunk.

If Sorkin’s adaptation lacks the subtlety and plainspokenness of Lee’s novel, it has moments of old-fashioned power—the playwright knows how to set up a court scene—and others of surprising tenderness, as when Atticus briefly takes the fatherless Dill under his wing. (“You have no business being kind, but there you are,” he tells the boy.) As befits material that has been a high-school mainstay for decades, this To Kill a Mockingbird has many teachable moments, perhaps a few too many. But it does—and I mean this as a compliment—a very decent job.

Shubert Theatre (Broadway). By Aaron Sorkin. Directed by Bartlett Sher. With Jeff Daniels, Celia Keenan-Bolger, Will Pullen, Gideon Glick, LaTanya Richardson Jackson. Running time: 2hrs 35mins. One intermission.

[Note: Greg Kinnear assumes the role of Atticus Finch beginning January 5, 2022.]

Follow Adam Feldman on Twitter: @FeldmanAdam

Follow Time Out Theater on Twitter: @TimeOutTheater

Keep up with the latest news and reviews on our Time Out Theater Facebook page