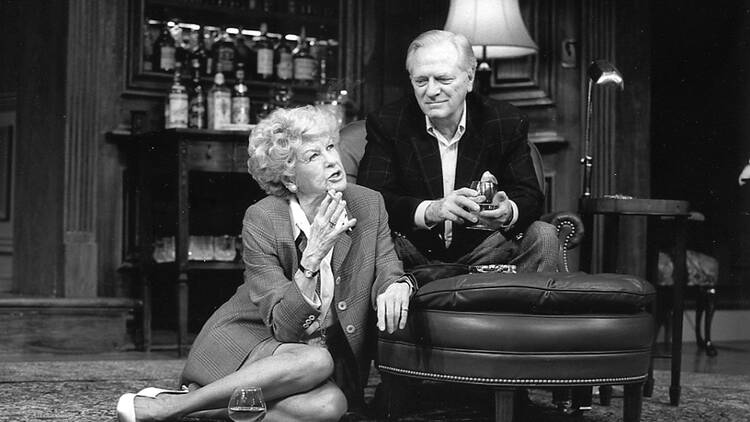

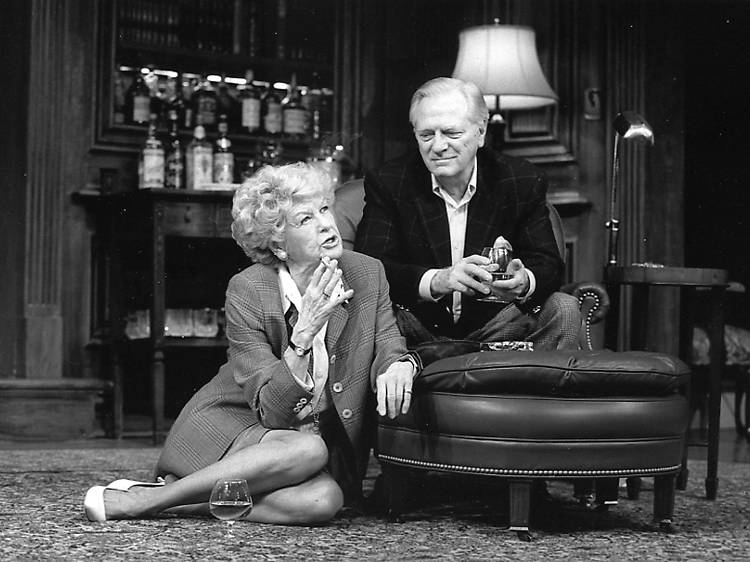

Raised in Captivity

The overbearing matriarch is to family drama as bloodletting is to Jacobean tragedy: inevitable, if usually overdone. Still, no one creates toxic moms like Nicky Silver (now heading to Broadway with The Lyons). Silver’s archly absurd 1995 comedy begins with a description of a mother’s death by hurtling shower-massage attachment, and gets stranger (and sadder) from there. Imprisonment is the apt, operative metaphor for Silver’s portrayal of the Bliss family (in an ironic wink to Noël Coward) and several of the impish playwright’s archetypes are present and accounted for: chronically celibate brother; crazy, self-obsessed sister; and soul-eating mother.—DC