Here’s a tip: Do not take Richard Foreman seriously. First, the experimental-theater titan’s perception-warping spectaculars require audiences to be ready to laugh at understanding, to spit in the eye of illusionist escapism, to tap-dance on the grave of linear thought. And second, he knows people overanalyze him. Should he start telling you about his elliptical, indescribable work, believe about 50 percent.

Certainly we’ve all recovered nicely from Foreman’s oft-threatened retirement, which has barely slowed his show-a-year pace. In 2009, he announced he was abandoning theater for film (the productive septuagenarian does have several movies in the works), gave up his venue, the Ontological-Hysteric Theater, and mounted the valedictory Idiot Savant at the Public. At Savant’s end, a giant deus ex machina duck puppet delivered a message as it exited: “Arrogant bastard people! Goodbye forever.” Since we now eagerly await Foreman’s latest, Old-Fashioned Prostitutes (A True Romance), at the Public Theater, the duck may have overstepped.

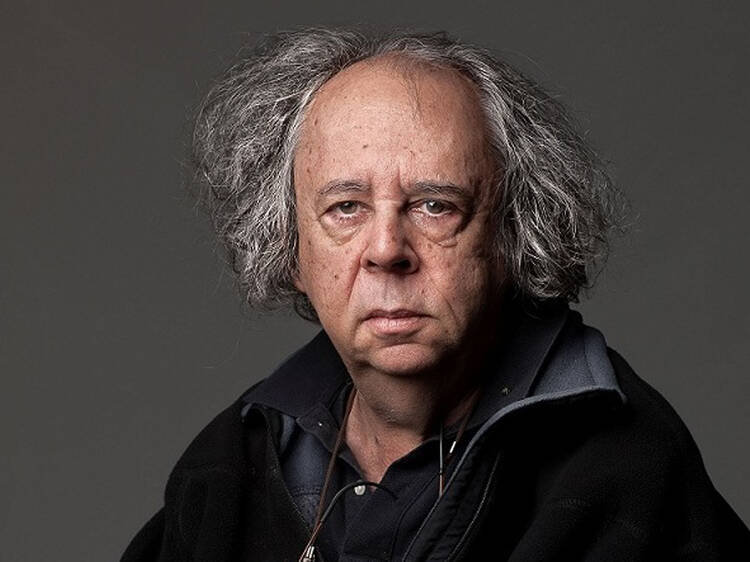

On a lunch break from rehearsal, the lightly rumpled Foreman chatted and continued to wax mischievous. As any fan knows, his texts stem from journal pages, lines grouped together for their intangible affinitive properties. Prostitutes is a collage of things he has written over the last ten years, yet he still claims that this is one of the first of his shows (“the first play that I know of”) to be autobiographical. (He has said this before.) Foremanland often features volatile men who find themselves both baffled and quasi-worshipped by a mysterious woman. In the new work, Rocco Sisto plays Samuel—a borderline-dangerous Southerner who navigates a surreal French café-cum-golf-course, pursues a coquette called Suzie (the elegant Alenka Kraigher) and changes his identity by adopting another, more “European” name. And in Samuel, Foreman sees himself.

The auteur’s total-theater pieces operate via vibration and proximity rather than logic or narrative—first he overwhelms us with his baroque sets (striped strings, candelabras, glaring lights), then he choreographs characters into a tension spiced with bizarre gags. (Here, the Michelin Man shows up, smoking a cigar.) So it’s not a one-to-one equivalency. Still, the director finds Samuel’s emotional state familiar: “It’s his sensation of being in a foreign city,” he explains. “I identify with the pretensions of being in a romantic environment and yet also being an awkward American.” Foreman pauses. “I identify with any awkwardness that you can imagine.” As he talks about being able to travel less as he ages, you understand his wistfulness about this particular atmosphere.

In a recent rehearsal, Sisto traded wistfulness for an electric, thrilling rage—and not all his fury seemed entirely performed. The Foreman process is sui generis: Actors work in full costume, on a set with lights and sound—all from day one. Recalls Sisto, “The script is nonlinear, and we were told to be off book the first day. I work fast; I did Salieri on Broadway in ten days! And yet, on the very first day?!? Alenka has done a workshop of the play; for me, it was literally The Actor’s Nightmare.”

Nearly every moment must be finessed a thousand times. “God almighty! Why are you doing that?” Foreman cries, watching a move that has been obsessively perfected. But Sisto cannot say he wasn’t forewarned, having appeared in another of Foreman’s Public pieces, What Did He See?, in 1988. “I wanted to work with him again to see if my memory of it was right,” Sisto says. “And oh, it was. On the credits for The Outer Limits, they used to say, ‘We control the vertical; we control the horizontal.’ And that’s Richard.”

Yet all this slipperiness, all this prickliness (Sisto says he isn’t sleeping), is in pursuit of something surprisingly pure. Foreman has long been a master of distraction. Despite his work’s sensorial maximalism, “there’s a Zen element in the writing,” he says. “All the junk says, ‘Look at this! Look at this!,’ but I’m making an environment that’s so complex you don’t see it anymore.” He goes on, “I’m used to a certain percentage of the audience feeling quite hostile—I don’t know why, I only make what I love! But then, I make work not for audiences, but for art history. I’m making it to exist in discussion with other art, poems and paintings that I really respect. I mean, I feel that way.” He hastens to add, “I’m not insane.” And that we can believe.

Click here for more details on Old-Fashioned Prostitutes (A True Romance).