Theater review by David Cote

Reviewing Miss Saigon is such a political minefield. I don’t mean arguing whether the 1989 musical fairly depicts the U.S. war against Communists in Vietnam. Rather, the challenge is to firmly call out Miss Saigon as a heap of Orientalist clichés filtered through 19th-century European melodrama and presented with all the subtlety of a coked-up, steroidal Michael Bay flick—while acknowledging that it provides work for a large number of Asian performers. Damn the show. and actors with too few opportunities lose jobs. You call that woke?

Not that one pan will make much difference. We are talking about a show that ran for a decade in the same venue, whose blend of trash and tragedy thrills tourists and those for whom Sondheim is too wordy and un-hummable. Cats is garbage too, but that slunk back and seems to be doing fine.

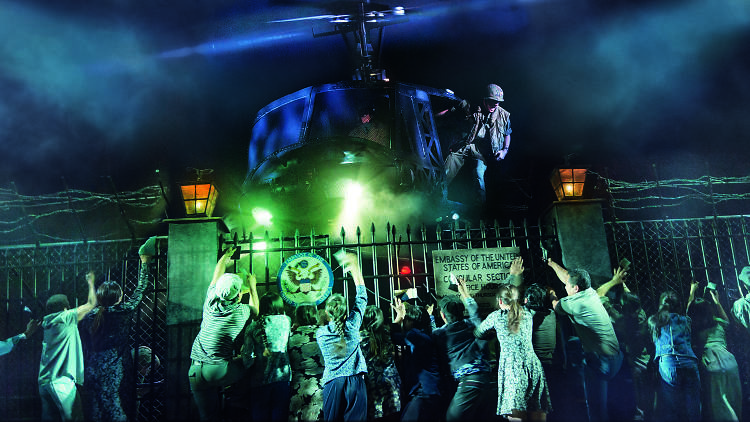

Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg’s follow-up to Les Misérables is explicitly about the fall of Saigon, but in a larger sense, it’s about the fall of the Anglo-European Broadway blockbuster. In terms of musical bombast, visual spectacle and hyperbolic vulgarity, it closed out a sad decade for the serious American musical. With a score heavy on lite rock and anthems, the show may be mostly sung, but it’s less a song-and-dance affair in any recognizable sense than it is an ’80s summer movie, weighed down with ridiculous special F/X. Of course that means the infamous helicopter, which arrives with fans ruffling the audience’s collective hair. (Totie Driver and Matt Kinley’s gorgeously cinematic production design is the one triumph here.)

The plot is borrowed from Puccini’s Madame Butterfly; the despair and grittiness is on loan from Oliver Stone and Apocalypse Now. Army grunt Chris (Alistair Brammer) falls instantly in love/lust/pity with Kim (Eva Noblezada), a virgin from the country forced into prostitution by a vicious pimp and profiteer known as the Engineer (Jon Jon Briones). Unbeknownst to Chris, his night with Kim results in a baby; he rotates back to the States, and she tries desperately to protect her son in Communist-overrun South Vietnam.

Historically, opera and music theater have mined the “East meets West” trope for works both brilliant (Pacific Overtures), dated but powerful (The King and I) and flawed but needed (Allegiance). Miss Saigon has plenty of pomp and angst, but its war-torn background and violent plot turns are only incidentally interested in South Asian culture or identity. Richard Maltby Jr. and Boublil’s lyrics are awfully leaden and generic, and Schönberg churns out predictably pseudo-Asian passages throughout the score—pentatonic patterns, flutes and plucked strings—the musicological equivalent of yellowface.

To be fair, the American figures are just as laughable and flat as their Vietnamese counterparts (let’s not forget that Frenchmen wrote this and the British produced it). Les Misérables is also broad and melodramatic, but a better source and greater historical distance mitigates its sanctimonious patches. However, like Les Miz, Miss Saigon is ultimately stranded between extremes of cynicism and idealism: the Engineer’s cartoonish hunger for American-style excess versus Kim’s bland, maternal purity. What’s lost in between is humanity or ambiguity, songs to tell us more about the characters’ past, their quirks or inner nuances. Instead, stereotyped villains and victims shout-sing at each others’ face or collapse and bellow, “Nooo!” (twice). Diversity on Broadway should be celebrated, but give actors of color characters we all can care about.

Broadway Theatre. Music by Claude-Michel Schönberg. Lyrics by Richard Maltby Jr. and Alain Boublil. Directed by Laurence Connor. With ensemble cast. Running time: 2hrs 40mins. One intermission. Through Jan 13.

Miss Saigon

Time Out says

Details

- Event website:

- www.saigonbroadway.com/

- Address

Discover Time Out original video