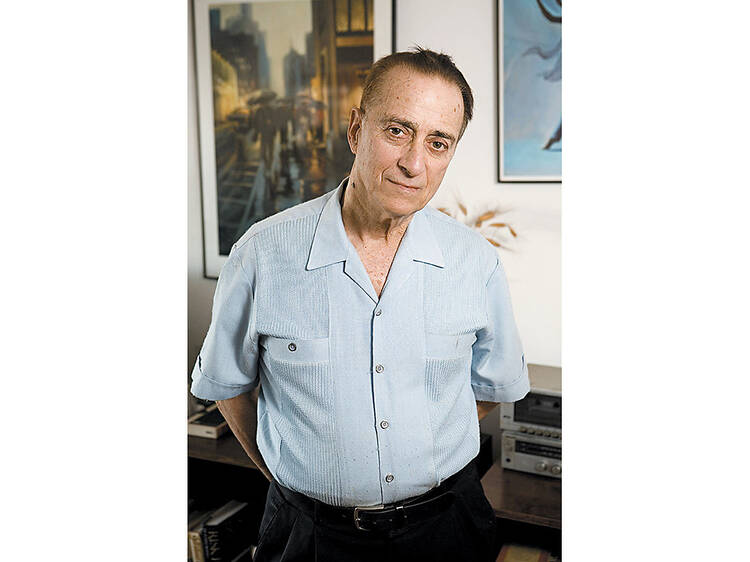

Rothenberg, 74, began his remarkable career trajectory as a press agent, working for the great Broadway showman Alexander Cohen. “Going to London and Rome for openings, working with Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor—it was very exciting,” he says. “But it was the ’60s, and I wanted to do a different kind of theater.” Striking out on his own, Rothenberg’s first project as a producer was the groundbreaking 1966 antiwar rock musical Viet Rock; but it was his 1967 production of John Herbert’s Fortune and Men’s Eyes, a drama about sexual slavery in prison, that put him on a new path. Once a week, Rothenberg invited former prisoners to join postshow discussions onstage at the Actors’ Playhouse. “I started meeting guys and women who had done time, and all my preconceived notions were immediately eradicated,” he recalls. “After a few months, I thought, We have the nucleus of an organization here. We can educate the public and change attitudes about prison! Ha ha ha. Naive as I was.”

Appalled by “the abject unfairness” of the penal system, Rothenberg founded a prisoners’-rights organization—the Fortune Society—and converted his 46th Street theater office into its headquarters. The group soon expanded its mandate, after an appearance on David Susskind’s popular TV show. “We thought we were going to change a lot of attitudes and get some speaking engagements,” he says. “Instead, the next morning I had 250 guys in the stairwell waiting for help. And Fortune evolved from that to be a service organization as well as an advocacy.” Rothenberg served as Fortune’s executive director for the next 18 years. (He was in the Attica prison yard during that institution’s infamous 1971 riots.)

Eventually, Rothenberg returned to the theater; his last Broadway show was 1999’s Waiting in the Wings. (“Working with Lauren Bacall was enough to send anyone into retirement.”) But he remained involved with the Fortune Society, and made regular visits to the organization’s Castle facility. It was there that he met the brooding Casimiro “Caz” Torres, who had spent 16 years in jail (on 67 arrests), and who wanted to write a book about his experiences. “I said, ‘Every third person has a book. Getting published is not realistic. But let’s dramatize it,’ ” Rothenberg recalls.

The result is The Castle, based on interviews that Rothenberg conducted with Torres and three other ex-prisoners: Angel Ramos, Vilma Ortiz Donovan and Kenneth Harrigan. (“We wanted people who had clearly made a commitment to a changed life.”) The four began performing the piece at fund-raisers, but seasoned producers Eric Krebs and Chase Mishkin—moved by the play’s harrowing tales of alienation and abuse—decided to give it a commercial run. “We never anticipated this,” Rothenberg says. “I mean, Caz used to sleep [at New World Stages] when he was homeless and it was a dollar movie theater. He was one of those discarded kids.”

Rothenberg hopes that the play will help educate its audiences about the cycles of criminality encouraged by current policies toward prisoners. “Talk about theater of the absurd!” he says. “Our prison system is devastatingly destructive to what we’re supposed to be about. But the upstate economy is dependent on prisons.” The process has been enlightening, too, for The Castle’s cast. “For me, it’s really therapeutic,” notes Torres. “Every time I do it, I feel something more. I’m grateful to the audience for giving me the option to speak about myself.”

Meeting people like Torres face-to-face, Rothenberg believes, will alter people’s attitudes toward ex-offenders. “The News had a story [recently] about people on parole, and the headline was SCUM WALKS THE STREETS,” he points out, with an edge of exasperation. “They’re not scum. They’re my friends, they’re my colleagues. They’re people who are welcome in my home.

The Castle is at New World Stages.

Discover Time Out original video