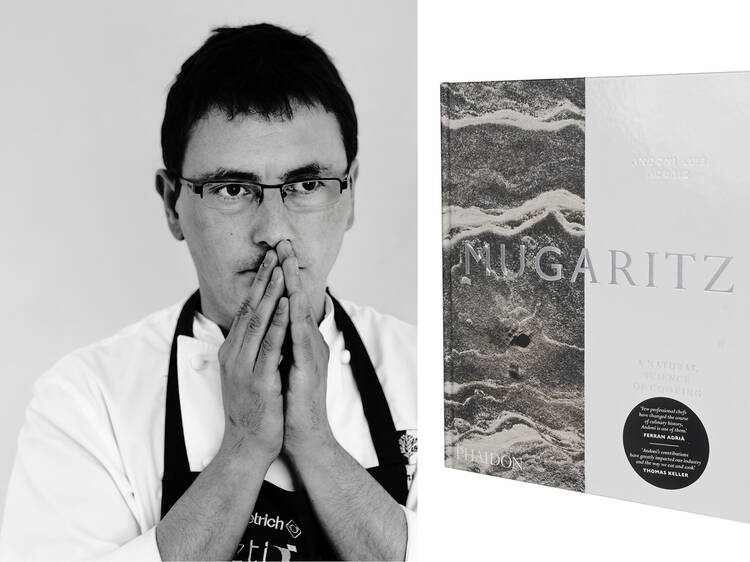

In New York, Andoni Luis Aduriz, the culinary mastermind of Spain’s Mugaritz, may not be as well-known as fellow Spaniard and international superstar Ferran Adrià of El Bulli or Copenhagen’s It boy, chef René Redzepi of Noma. But attentive diners may already know his work. We’ve seen ash and hay—ingredients brought into the kitchen at Mugaritz many years ago—pop up recently at cutting-edge eateries like Gwynnett St., whose chef, Justin Hilbert, did a stint at the cutting-edge Spanish restaurant. A movement toward wild foraged ingredients, pioneered by Aduriz in 1998, is also on the verge of exploding in Gotham. It’s evidenced at Isa, Frej and Atera, helmed by another Mugaritz alum: James Beard Award winner Matthew Lightner. For years, Anduriz’s groundbreaking temple of gastronomy has drawn ambitious young chefs and adventuresome diners for its wildly innovative multicourse meals, which showcase artistic flights of fancy and feats of science, such as edible cocoa bubbles and “crabmeat” made from Jerusulam artichokes. We’ll likely see more of Mugaritz’s influence soon. On May 27, Aduriz’s first English-language cookbook hits shelves, bringing his recipes, techniques and ideas to a much wider audience. We sat down with the toque, and translator Annie Sibonney, when he came through New York to talk about inspiration, edible rocks and his time working at El Bulli.

Time Out New York: The subtitle of the book is “A Natural Science of Cooking.” What does that mean to you?

Andoni Luis Aduriz: We thought a lot about the name. People have always seen Mugaritz as one of the first restaurants to go out into the forest to get wild herbs. But Mugaritz is [also] one of the restaurants that has been working with scientists on research. This theme of molecular gastronomy [at Mugaritz] has been hidden. We thought we should provoke the idea that natural ingredients and science [may] contradict one another—[but] the two unite at Mugaritz.

When Mugaritz first opened in 1998, the dining room was empty. How did you deal with that at the time?

Mugaritz has had a lot of success, but it’s based on many small failures. What brought us here is our will. Will is like water—it [finds a way through] all the obstacles. Nobody came [at first] because we were in the [middle of nowhere]. I had a lot of time on my hands, and I thought to myself, What do I do now? Let’s go to the mountains [and forage].… When you have a restaurant that’s not doing so well and a diner comes, it’s not just a diner for you, it’s a collaborator.… That’s why we started, really, with the wild herbs. It wasn’t just herbs as an ingredient, it was herbs representing what we wanted to give the diner. Those diners were literally giving us life, and we wanted to give them something that money couldn’t buy.

You worked at El Bulli with Ferran Adrià and his brother Albert in their early days there. What was it like?

When I arrived at El Bulli, it was a very singular, very unique restaurant. There were days when we had zero guests in the dining room, and others when we had four, eight or ten. The second year that I was there, they couldn’t pay me my salary. I had to rent an apartment on my own, and every 15 days, I would go and ask for a little bit of money and then a little bit more money. Financially, it was a huge problem.

But Ferran was a man of conviction. He knew that he was working to achieve something incredibly unique. He was just about creativity, the best ingredients possible, concepts and total freedom. And when a client came, we did everything to give them the best that we had. If I hadn’t lived through that, Mugaritz wouldn’t exist.

What impact did El Bulli have on you?

El Bulli taught me that the bigger and more advanced the project is, the longer it will take to achieve it. The first eight years of Mugaritz were incredibly complicated. If I had thought like most people think, I would have worked just to get the maximum number of guests. I wouldn’t have worked to do the best I possibly could. They are two totally distinct things.

Are there any U.S. chefs whom you admire?

When I started [cooking], chefs I idolized were doing things differently. This motivated me, and I learned a lot from their work. But my teachers after that were really the young chefs who worked for me.… They were there to learn from me, but I [learned] from them. Thomas Keller’s work is [also] very inspiring and always has been. Wiley Dufresne too, as well as people like Harold McGee.

Did you visit any restaurants in New York during your time here?

We went to wd~50. Wiley is one of my great friends. What David Chang does is also incredible. Thomas Keller’s Per Se, [Daniel Boulud’s] Daniel and all of these people that are doing more formal dining, they’re brilliant.

In the book, you say, “[Diners] don’t have to like something to enjoy it.” What do you mean by that?

You’re not born automatically understanding everything. Beauty is something that people learn to understand; it is a cultural concept. I’m from a very small town in the Basque country. As a child, I used to watch Sesame Street, and there were all these episodes where the same boy used to always say, “My favorite food in the world is pizza!” I used to think, Wow, how strange are Americans? Pizza? But if it’s something so delicious, I want to try it. I had my first pizza when I was 13 or 14 years old, and I was disappointed. What was the problem? The problem was that I didn’t know it. I hadn’t ever had it before. And nobody taught me how to decode or how to understand what I was eating.

So how do you avoid disappointing diners who have never had your food before?

Between myself and the rest of my team at Mugaritz, we work more than 12,000 hours a year, just on creativity. We are part of the culture where we are born, but we [also] travel all around the world, work with different farmers and suppliers, and put in lots of hours of investigation, research and reflection. I am all of the books that I’ve ever read and all of the food that I’ve ever eaten. I take everything, combine it together and shake it.

The person who comes to Mugaritz normally doesn’t have the opportunity to do that. You come to Mugaritz, and I take your hand and I lead you. Notice this texture. Notice this aroma. Notice that this is going to impact you because you have a prejudice against it. I take you on a journey of 20 dishes. If I don’t explain everything to you well, the problem is mine, not yours. That doesn’t mean that you are going to like [everything] or that it’s going to be good. But it’s sincere, and if it’s sincere, it’s the only thing that I can offer.

Among other things, you’re known for your edible stones—trompe l’oeil potatoes covered in kaolin clay. What other surprises are in the book?

There are some things in this book that are incredible. Natural ingredients are filled with possibilities and they’re just as spectacular as all the new products and ingredients. We have meringues that are not made from egg whites; they’re made from a type of seed. There’s a dish that seems like a ripened rind cheese, but it’s not fermented; it’s made from flax and milk.

We also make [translucent] skeletons of leaves. It’s a two-week [process] with camellia leaves; [several] solutions of alkaline solution, ash and baking soda; oven-toasting; and oven-drying with honey. It is autumn on a plate, but it’s also what autumn represents—the passing of time, the melancholy that it generates. We worked so long on it. It’s pure poetry.

Related

See more in Food + Drink