[title]

In a city of well over 1,200 sushi restaurants, only a few have female chefs. Yes, New York City, one of the country’s (OK, the world’s) most progressive, inclusive and esteemed culinary hubs, is home to fewer than five women leading sushi counters. And in many ways, they couldn’t be more different.

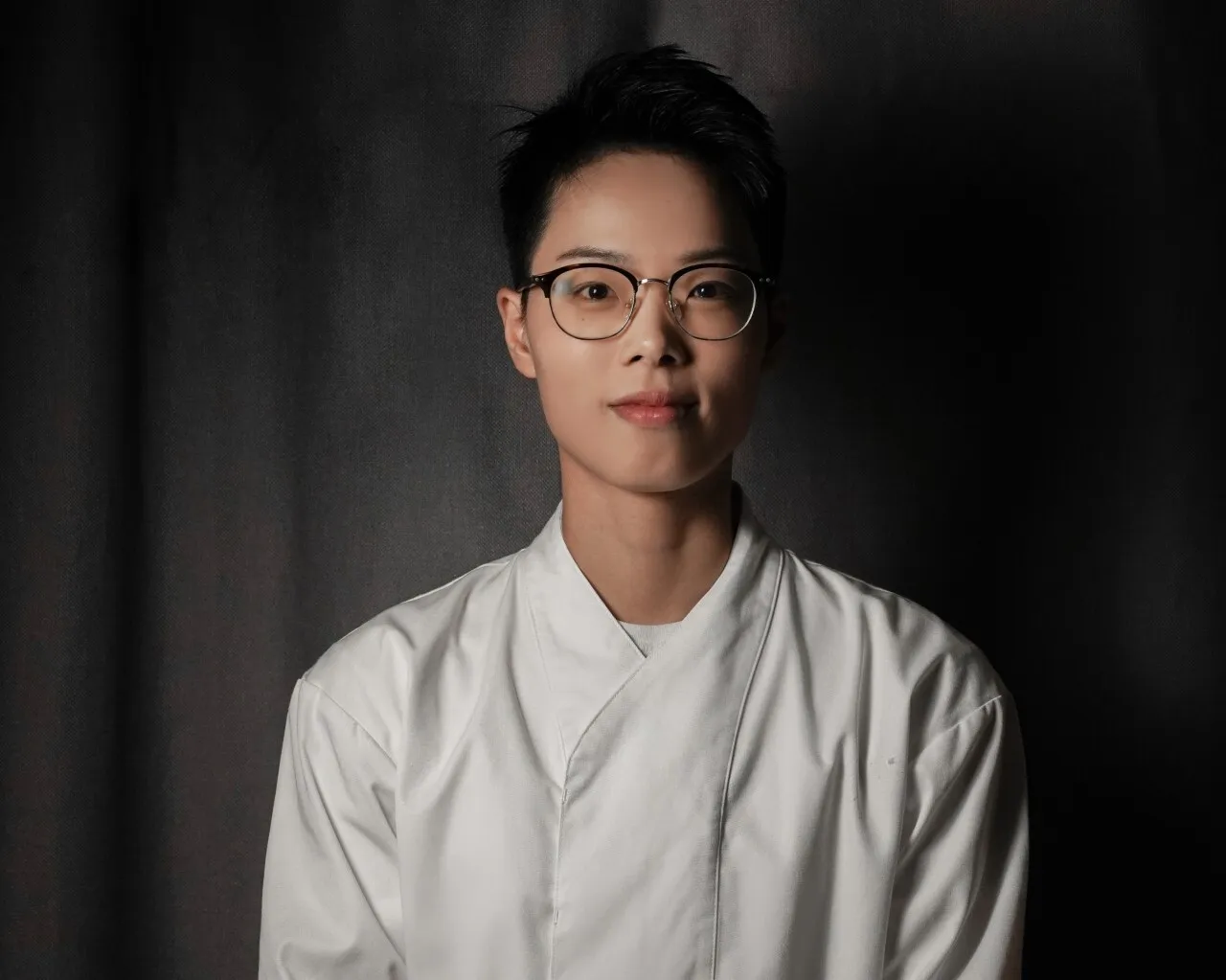

Nikki Zheng, a high-end sushi alum of Masa and Nakazawa, opened her own omakase restaurant, Sushi Akira, on the Upper East Side in early 2025, serving 18 courses for $175. Morgan Adams runs Hōseki, the jewel box, six-seat omakase counter offering luxury lunches beneath Saks Fifth Avenue. Both feel the extreme gender gap in the sushi world.

RECOMMENDED: The best Women’s History Month events in NYC

“I think being a woman in a lot of industries can be difficult,” Adamson tells Time Out New York. “I have found [my job] comes with some instant judgments, but I have decided to lean on the advantages it has given me. I get to change people's minds rather than disappoint. If people's expectations are already low, I have nowhere to go but up. I've had a lot of support from guests—especially other women—who are excited to see someone different behind the counter.”

Adamson started making sushi upon learning that her favorite sushi restaurant in her hometown of Kalamazoo, Michigan, was hiring. She wanted to work with her hands in a kitchen setting, and a love for making sushi was born.

“I enjoy how tactile making sushi is. I appreciate how close to the product and the guest I get to feel. It’s more intimate than any other job I’ve had,” Adamson says. “I get to make a more direct impact: selecting the products I think are best, breaking the fish down, portioning it, prepping it for service, and then all the parts that follow, including taking care of guests directly in front of me, making people feel seen and genuinely important.”

“I've had a lot of support from guests—especially other women—who are excited to see someone different behind the counter.”

That visibility, however, hardly extends to female sushi chefs. “I have found a few women mentors and quickly gravitated towards them. They are open to sharing knowledge and I find them to be people with a lot of skill because they have been forced to prove themselves over and over,” Adamson adds. New York based Sushi chef-turned-artist Oona Tempest and California sushi chef Amberly Ouimette have offered support.

“I’m always the only woman,” says Zheng of the sushi restaurants she’s worked at, including her own. “It’s kind of tough. Customers have assumed I’m the apprentice, not the chef. Some people hesitate when they see me behind the counter, or I can tell from their [initial] facial expressions that they may have some misconceptions or outdated beliefs. I don't challenge these kind of assumptions with any words. I just prove them wrong with my work. I always show them with my skills, dedication, and of course, I love smiling.”

“I just prove them wrong with my work.”

The precision and pressure of making sushi drew Zheng to the cuisine over a decade ago. “I like a challenge, so my path was probably always leading to be a sushi chef,” she adds. ”Some people think it looks very simple, but it's very difficult. There’s nowhere to hide the freshness of the fish, the temperature of the rice. Every element determines if each piece will be a success or fail. I am obsessed. It’s a lifelong discipline. You refine every detail day by day. ”

At Sushi Akira, Zheng sees herself as building a bridge between herself, the ingredients and the customers. It can be a space where folks will try something new and surprise themselves or return for beloved treats or an off-menu special created by Zheng. Through this intrigue and visibility, she sees a space where gender bias in sushi can be alleviated and more women can break into the cuisine.

Adamson agrees: “I’m excited to see more and more female sushi chefs opening up their own spaces because I think that’s where some serious innovation can emerge.”

Leaving customers with a taste for more, or at least, a fond memory of Zheng’s omakase, helps push boundaries for folks to envision what contemporary, high-end sushi culture can look like.

”In Japanese culture, omakase is not just a meal,” Zheng says. “It's going to be a dialogue between chefs, customers, servers and also about the seasonal ingredients. When I'm working at Sushi Akira, my job is to make that conversation unforgettable.”

Sushi Akira, located at 317 E 75th Street, is open 5pm-11pm Tuesday through Sunday; Hōseki, inside Saks at 611 Fifth Avenue, is open noon to 4pm Tuesday through Saturday.