[title]

I’ll say it with my chest: Pete’s Tavern is the personification of Christmas in New York—and I know it has pretty stiff competition: the tree at Rockefeller Plaza, the decorated windows along Fifth Avenue and the Rockettes.

But Pete’s Tavern beats them all.

Every December, year after year, the warm red glow from the windows of Pete’s Tavern beckons to New Yorkers. Unlike the city’s more mainstream Christmas destinations (Rolf’s, Frosty’s and Miracle on Ninth), Pete’s serves as a beacon of holiday cheer for the locals. It provides a warm and festive respite for New Yorkers eager to get away from the teeming hordes of tourists that descend on our city this time of year.

It’s time we discussed the hidden secrets of New York’s truest Christmas destination.

It was a Grocery and Grog store

Pete’s Tavern traces its roots back to 1851 when the building on the corner of East 18th Street and Irving Place was first constructed. For many years it operated as the Portman Hotel. In 1864, the hotel opened a “grocery and grog” store on the ground floor which served cold sandwiches and—you guessed it—grog. Pete’s cherished draft beer, the 1864 Ale, pays homage to these humble beginnings. In 1899, the hotel was bought by two brothers, Tom and John Healy. Shortly thereafter, the old “grocery and grog” store was given a facelift and renamed Healy’s Café. The hotel’s stables were converted into a proper dining room and the Healy brothers started offering a meal service. Bar patrons entered through the door on Irving Place while dining room patrons would enter through the door on East 18th Street. This split entry system helped the ladies who took their meals at Healy’s Café avoid having to walk through the boisterous male-dominated saloon on the way to their table.

Peter D’Belles purchased the establishment in 1922 and renamed it Pete’s Tavern. Over the past 100 years, Pete’s has remained largely unchanged. The curved rosewood bar, beveled mirror, liquor cabinets, tin ceiling, and tiled floor are all original fixtures dating back to 1864 and the “grocery and grog” store days. The oaken booths have been there since at least its Healy’s Café days—perhaps longer.

Then it was a “flower shop”

In 1920, the enactment of the Eighteenth Amendment and the grim onset of Prohibition brought the liquor business to a screeching halt throughout the United States. Every bar, tavern and saloon was forced to shutter its windows and close up shop. Well, that is, almost every bar. Pete’s Tavern was saved from this tragic fate by an unlikely hero: Tammany Hall.

For approximately 100 years between the mid-19th and 20th centuries, New York City politics were dominated by Tammany Hall, a political club of Irish-American ruffians who turned city governance into their personal cash cow. Its most famous member, William “Boss” Tweed, stole about $200 million (about $3.5 billion in present value) from public coffers in the 1860s-70s and ultimately died in jail.

During Prohibition, Tammany Hall’s headquarters were located on Union Square—just a short walk from Pete’s. The tavern was the favorite bar of the famously corrupt political club’s members. So, in the 1920s, Tammany officials conspired with Peter D’Belles to keep the bar open despite the nationwide ban on such establishments. The dining room was converted into a half-hearted flower shop while the front of the bar—with its entrance on Irving Place—had its windows blacked out and its doors locked. To reach the bar, Tammany officials would enter the flower shop, walk up to the refrigerator, and ask to see where they “kept all the flowers.” The store’s employees would then swing open the dummy refrigerator door to reveal Pete’s iconic curved rosewood bar and usher the guests inside into the only (somewhat) legally sanctioned drinking establishment in Prohibition-era New York.

Time Out Tip: You can still see the hinges from the dummy refrigerator door, which are attached to the door frame separating the bar from the dining room.

It became the embodiment of the Christmas spirit

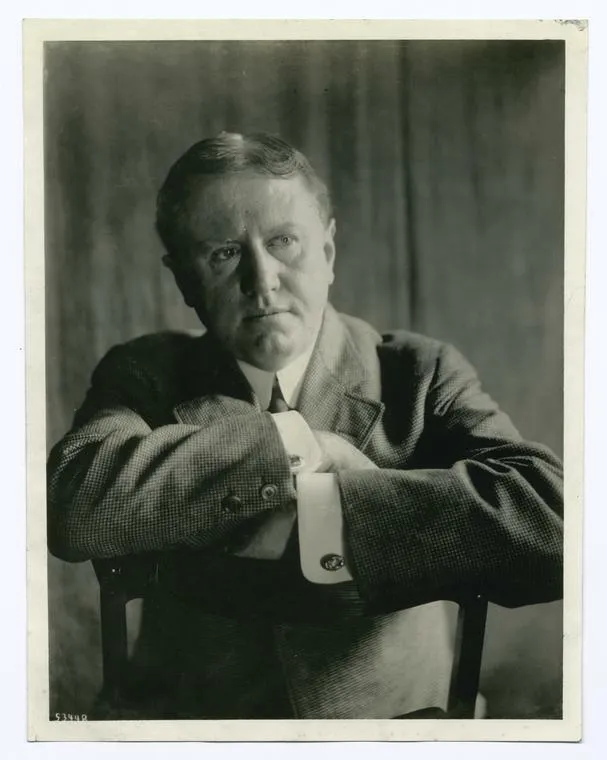

In the early years of the 20th century, William Sydney Porter lived at a boarding house at 55 Irving Place—just down the block from Pete’s (then, of course, known as Healy’s Café). Porter came in nearly every night to sit in his favorite booth—the second booth from the entrance—and write. Legend has it that one snowy evening in 1903, Porter came in particularly inspired. He ordered his beer, sat in his usual booth and began to write feverishly. After a few short hours (and likely several pints), he got up and left taking a cluster of hastily scrawled pages with him.

Two years later, the story he crafted that night was published in the New York Sunday World under Porter’s preferred pseudonym: O. Henry. That story, “The Gift of the Magi,” went on to nationwide fame as a treasured tale that touched millions of hearts. In “The Gift of the Magi,” O. Henry tells the bittersweet story of two lovers who each sell their most prized possessions to be able to buy the other a gift. The wife sells her beautiful brown hair so that she can afford to buy her husband a platinum chain for his pocket watch. Meanwhile, the husband sells his pocket watch to buy his wife a set of ornamental combs for her hair. The heavy moral lesson Porter embedded in the story has become one of the most common representations of the Christmas spirit in American culture. And the entire tale was hatched—beginning, middle, and end—in a cozy oaken nook in Pete’s Tavern.