[title]

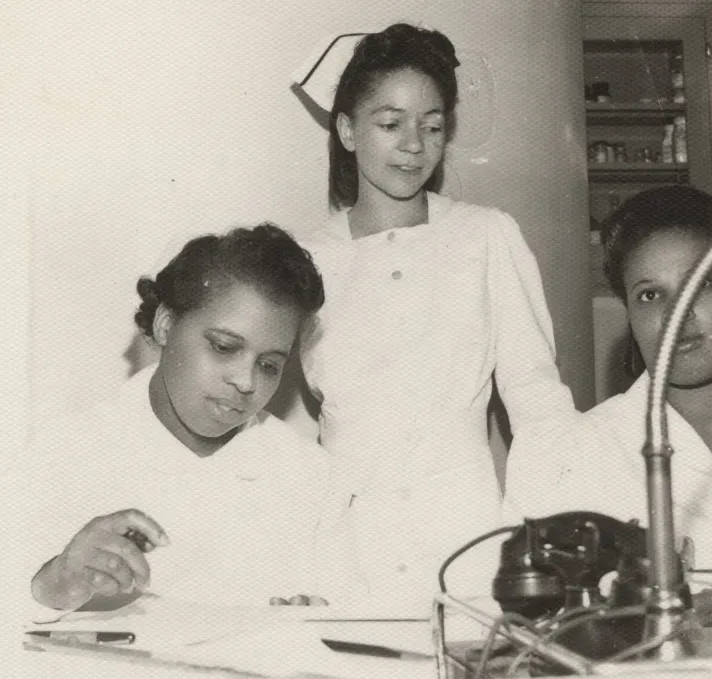

It’s no secret that the U.S. is particularly astute at obscuring history it's not very proud of, which has left us with limited knowledge about this country’s past. Among the historical figures who were never given their flowers were the Black Angels, a group of nurses who risked their lives to take care of tuberculosis patients at Sea View Hospital in Staten Island and who were an important part of reducing deaths from the bacterial disease in the U.S.

Now, you can learn more about the nurses at the Staten Island Museum’s newest exhibition, “Taking Care: The Black Angels of Sea View Hospital,” which highlights the stories of these little-known figures of New York City’s history.

RECOMMENDED: The best Black History Month events in NYC

In 1951, Sea View Hospital tested a new treatment for tuberculosis, an illness which killed one out of every seven people living in the United States in the 19th century, per the CDC, and was also responsible for 18% of all deaths in New York City in the early 20th century.

Because tuberculosis is highly contagious, many white nurses refused to work with TB patients, and Black nurses from around the country were recruited to do the job at the Sea View Hospital, per CBS News. All in all, Sea View Hospital recruited around 300 nurses to care for thousands of patients and, in turn, they were one of just four municipal hospitals in the city that did not discriminate or have quotas against Black nurses, per the New York Times.

The exhibit, which opened on January 26, includes heirlooms from the nurses, oral histories from their families, and a film installation called Back and Song by artists Elissa Blount Moorhead and Bradford Young, which focuses on wellness and the Black experience in America from the perspective of several different Black healers. The exhibit also highlights the story of 93-year-old Virginia Allen, a Black Angel who now resides at Sea View.

As COVID taught us, public health is a social justice issue, too. During COVID-19, Black, Hispanic and Asian Americans were more likely to die from COVID-19 than their white counterparts, per the Kaiser Family Foundation. Understanding the interconnectedness of race, class and public health is at the heart of the exhibit’s message.

"Tackling public health challenges, such as the widespread prevalence of tuberculosis, represents a pivotal chapter in the annals of medical history," Brahim Ardolic, MD, executive director at Staten Island University Hospital said a press release about the exhibit. "The efforts to understand, prevent, and treat diseases on a community level not only shaped the trajectory of healthcare, but also highlights the resilience and dedication of those who contributed to the well-being of society."

The exhibit also hopes to bring awareness to the fact that tuberculosis is on the rise in the U.S. for the first time in decades. For more information on the exhibit, you can visit the Staten Island Museum's website here.