[title]

The Village Vanguard has seen and survived it all—wars, floods, fires, economic downturns, and the fallout from the September 11 attacks—but the current forced closure of music venues might just be the thing that breaks the camel’s back, according to owner Deborah Gordon.

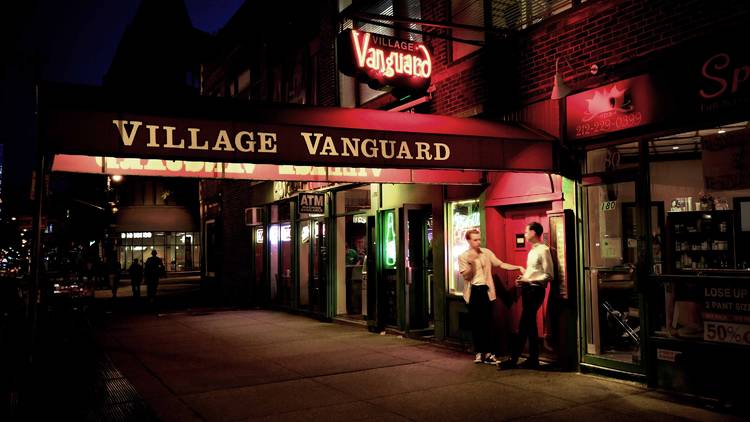

Her father, Max Gordon, opened the small club in 1935 for poets and artists, but it became a major jazz hotspot by the 1950s, eventually welcoming musicians like Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk to its stage. Since then, it’s become a fundamental piece of the Greenwich Village jazz scene under the management of Gordon’s wife Lorraine and daughter, Deborah.

Known for its intimate atmosphere, the venue lets musicians and audience members jive together, with just 123 seats in the entire space.

The beloved club, like other music venues in New York City, has been sitting empty since mid-March with no end in sight. Deborah Gordon and her fellow music venue owners are waiting for the government to greenlight reopenings, or at the very least provide some financial assistance. For now, they’re all surviving on donations and small ticket sales for live-streamed performances, but if things remain this way, closure could be imminent.

“I couldn’t deal with the idea of closing for a month, let alone where we are, let alone there is no foreseeable end to this,” Gordon tells us. “It’s a kind of limbo that we’re all in. It’s cold comfort to be able to say we’re all in the same boat.”

The Village Vanguard has had to pivot to streaming performances online to keep some sort of revenue stream and stay connected to its community. It was a necessary adaptation that hasn’t given the space the return it was hoping for.

In order to stream sets live and charge $10 per ticket, the club had to invest in major video and sound equipment.

“We took a deep breath and realized [COVID-19] is not like our leader said—it’s not going to disappear—so we talked about a pivot: going from being a club where people come in to what now looks like a studio,” Gordon said. “It’s a crowded frontier...it’s a bumpy stream and way more difficult than we ever imagined it would be. I think there was a misapprehension that we’d open the flood gates and people would just come, but nothing could be further from the truth. We’re finding that it’s very hard to find your audience, to keep your audience, and to grow your audience. It’s a whole different world.”

Organized and ready to fight for help

According to the National Independent Venue Association, Pollstar is estimating a $9 billion loss in ticket sales alone, not counting food and beverage revenue, if these spaces remain shuttered through 2020. And of NIVA’s 2,800 members (independent venues across the nation) including The Village Vanguard, 90 percent of them say they’ll be forced to close permanently in a few months without federal funding.

More than New York City 70 venues have joined NIVA, including jazz venues like The Village Vanguard, Joe’s Pub, Birdland, Blue Note, Cafe Wha?, Arthur’s Tavern and other Village clubs like Groove, City Winery, Terra Blues and The Bitter End.

NIVA, which was formed by venue owners and musicians during the pandemic shutdown, is pushing the federal government to provide long-term assistance to shuttered venues, relief through tax credits, and a continuation of unemployment insurance benefits. (Specifically, it supports the RESTART Act, the Save Our Stages Act, and the Entertainment New Credit Opportunity for Relief & Economic Sustainability Act.) Through SaveOurStages.com, two million emails have been sent to legislators asking for federal assistance.

“Our businesses were the very first to close and will be the very last to reopen—if we’re lucky enough to exist through it,” said Audrey Fix Schaefer, the spokesperson for NIVA. “We have zero income, enormous overhead and no vision of when we can reopen. If they invest in us now, we can be part of the economic renewal that happens when the country reopens again.”

Fix Schaefer, who owns three music venues in D.C., said that she has seen mom-and-pop businesses make it through all kinds of difficult situations but have found a way to keep afloat and recalibrate. This time, however, it’s a situation akin to eminent domain, where the “government has taken our business but they’re leaving us hanging up to dry,” she said.

“There is just no way, no amount of business acumen, creativity or determination to allow us to last forever with the rents we get charged with no revenue and no meaningful help,” she added. “While the PPP program was well-meaning and helped a lot of industries, it will not save ours.”

A huge potential loss for NYC culture

The closure of Greenwich Village’s jazz clubs, in particular, would be a major cultural loss for New York City. According to Andrew Berman, the executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, the neighborhood’s history is connected to jazz because it was the only place in NYC where integrated clubs existed—the first being Cafe Society on Sheridan Square, where Bayard Rustin, who would go on to organized the 1963 March On Washington, was first exposed to radical politics, and where Billie Holiday debuted her anti-lynching lament, “Strange Fruit.”

“Since the mid-19th century Greenwich Village has been the artistic capital of New York, and so musicians and all those looking to push the boundaries of society gravitated towards the neighborhood,” Berman said. “Throughout much of the 19th century, it also had the largest African-American community in New York. So the roots of jazz are deep in the neighborhood. We are very concerned about the effect the pandemic is having on all our performance venues, cultural institutions, and indoor public gathering spaces, especially jazz clubs.”

Because of that, GVSHP is promoting legislation that would give small businesses like jazz clubs a break on their rent during COVID-19 by providing state and federal funds to pay for a significant portion of the rent, while requiring landlords and commercial tenants to cover the shortfall.

“It is terrifying to think what our neighborhoods could look and be like if the rate of closures of businesses like this continues unabated,” Berman notes.

An unbreakable scene

Jazz musician Daniel Bennett of the Daniel Bennett Group, who has played at Greenwich Village clubs for years, says that its clubs had been packed before the pandemic hit and most venues featured multiple bands every night. Tourists from around the world were coming to the Village to hear music at Smalls, Mezzrow, Blue Note, Village Vanguard, 55 Bar, and Zinc Bar among others.

The Greenwich Village jazz scene has also fostered new talent from across the globe.

“Music students at New York University and the New School can actively tap into the Greenwich Village jazz scene,” Bennett said. “I played my first gigs in Greenwich Village at Cafe Vivaldi and the Sidewalk Cafe many years ago. I always feel at home when I'm performing in the Village. It’s a great place for young people—you can walk a few blocks and catch new music at dozens of jazz clubs.”

During the shutdown, the Daniel Bennett Group (a quartet featuring saxophone, clarinet, flute and Oboe) has been playing outdoor concerts at The Canary Club and Tomi Jazz almost every week and sees Greenwich Village jazz clubs making it work through daily livestreams and outdoor concerts, which New Yorkers have gotten to enjoy this summer.

The SmallsLIVE Foundation has gotten a $25,000 donation from Billy Joel to keep streaming going at the Smalls and Mezzrow clubs, helping musicians to continue playing gigs, according to The New York Times.

The owner of those clubs, Spike Wilner, said in a recent newsletter that about 20,000 viewers on average tune into each show from all over the world.

"I've said it before but jazz is like a tenacious weed that refuses to die, one that can grow in any crack in the pavement and rise strong[ly] to the sun," he wrote. "Here is our music popping up anywhere that it can be played—outdoor cafes, parks, tents. Jazz will live and so will our community. I remarked to my hardworking general manager, Carlos Abadie, that the community and scene [are] still intact but just need a house to live in. Jazz will live and so will Smalls."

Bennett also says New Yorkers won’t let the scene die and that it’s “unbreakable.”

“Jazz clubs are mobilized as the city continues to bounce back,” he said. “We have a deep-rooted history that will carry us through the pandemic. We have unlimited talent and creative energy. The Greenwich Village jazz scene has stood the test of time. This virus will die, but our cultural renaissance is just beginning!”

As for The Village Vanguard, Gordon urges people to vote to maintain some hope.

"Once we lose hope, what have we got? We have to keep hope to be able to see our way through this...I think we will."

Most popular on Time Out

- 26 notable NYC restaurants and bars that have now permanently closed

- The world’s first-ever makeup museum is now open in NYC

- The 8 rooftops now open with the best views of NYC

- 12 things New Yorkers do that are actually disgusting

- NYC venues and concert halls that have now permanently closed

Get us in your inbox! Sign up to our newsletter for the latest and greatest from NYC and beyond.