[title]

As she donned the black robe for her role on the Supreme Court, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was known to adorn the traditional garment with a wide array of collars and necklaces.

Now, her fashion is getting the spotlight in a new photography exhibit called "RBG Collars: Photographs by Elinor Carucci." See it at The Jewish Museum on the Upper East Side from December 15, 2023, through May 27, 2024.

RECOMMENDED: A first look at The Met’s fabulous, feminist exhibit ‘Women Dressing Women’

The installation features two dozen photographs of the late justice’s collars and necklaces taken shortly after Ginsburg died in 2020. This is the first time the Carucci’s photographs are being shown at the Jewish Museum since the images were acquired in 2021.

Ginsburg, the second woman to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court, wore collars to emphasize the long overdue feminine energy she brought to the court, the museum explained. She also used collars to encode meaning into her dress—a sartorial strategy practiced by powerful women throughout history.

At first, she wore traditional lace jabots, then gravitated toward necklaces made of beads, shells, and metalwork from around the world, often gifted by colleagues and admirers.

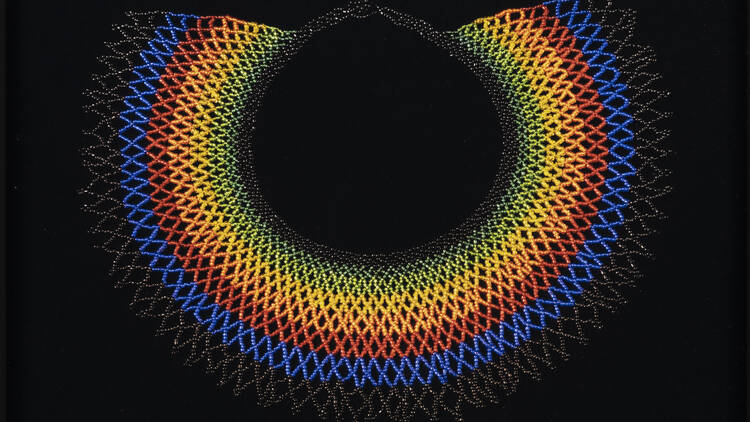

Some collars packed a sartorial punch, as TIME Magazine explained in a feature. For example, on days she dissented, the liberal justice often wore a bejeweled collar that looked like armor. On days she announced the majority opinion, she often wore an ornate yellow piece. She also was seen wearing a "Pride collar" with a rainbow of colorful beads.

Eventually, her style helped to make her a feminist pop culture icon known as “the Notorious RBG” whose image with her glasses and collars adorned tote bags, T-shirts and tattoos.

"Seen as a whole, the photographs of these collars offer a collective portrait of the late Justice through these objects imbued with her personal style, values, and relationships," the Jewish Museum said in a press release. "While Ginsburg often chose them on a whim, she occasionally used them as a form of wordless communication; in every instance, they served as a reminder that her august responsibilities were carried out by a particular human being."

The installation will also include other jewelry from the museum's collection as a way to explore the possibilities as well as the cultural and religious aspects of adornment. Some feature special inscriptions, while others bear compartments in which special scrolls can be stored. Many of the pieces were made and worn by people from all corners of Jewish history, quite different from the world in which Ginsburg lived. But, the museum explained, they all understood how jewelry can be used to express individuality at times when the opportunity for self-expression is limited.

While Ginsburg often chose them on a whim, she occasionally used them as a form of wordless communication.

For Ginsburg, her Jewish upbringing in Brooklyn during the 1930s and 40s was formative to the person she became. She grew up at a time when “the horrors of the Holocaust unfolding in Europe cast ominous shadows over antisemitic slights encountered at home,” the museum said.

The Jewish principle of tikkun olam (repairing the world) guided her work, as she wrote many notable opinions that helped to advance legal protections for women and members of other historically marginalized groups.

As a photographer, the still life series of Ginsburg's collars is a departure from Carucci's usual work examining intimacy, family, motherhood and women in moments drawn from her own life.

"Yet," Carucci told The Jewish Museum, "I still see this project as being just as personal as any of my other work. Ruth Bader Ginsburg held special significance for Jewish women like me who dreamed of living a life that combined career success with tikkun olam."